eBook - ePub

Varieties of Memory and Consciousness

Essays in Honour of Endel Tulving

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Varieties of Memory and Consciousness

Essays in Honour of Endel Tulving

About this book

These collected essays from leading figures in cognitive psychology represent the latest research and thinking in the field. The volume is organized around four "Endelian" themes: encoding and retrieval processes in memory; the neuropsychology of memory; classificatory systems for memory; and consciousness, emotion, and memory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Varieties of Memory and Consciousness by Henry L. Roediger, III,Fergus Craik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

ENCODING AND RETRIEVAL PROCESSES

1 | Explaining Dissociations Between Implicit and Explicit Measures of Retention: A Processing Account |

Rice University

University of California, Santa Cruz

Purdue University

Explicit measures of memory refer to tasks in which people are directly tested on episodes from their recent experience; in performing the tasks people are instructed to remember events and presumably are aware that they are recollecting recent experiences. Implicit measures of retention are those on which subjects are not told to remember events, but simply to perform some task; retention is measured by transfer from prior experience (relative to an appropriate baseline), and presumably conscious recollection is not necessarily involved (Graf & Schacter, 1985). Explicit memory tasks are the standard warhorses of the experimental psychologist’s armamentarium for investigating memory: free recall, cued recall, recognition, and various judgments (frequency, modality, feeling-of-knowing, etc.). Implicit measures of retention are transfer tasks in which performance on the critical task is influenced by prior experience, without the prior experience necessarily being reflected on explicit measures. Examples of implicit tasks are reading inverted text, naming fragmented words or pictures, or naming words or pictures from brief displays. Great interest has recently been displayed in the relation between explicit and implicit measures of retention, because they are shown to behave differently as a function of many independent variables (Schacter, 1987). The purpose of the present chapter is to consider functional dissociations between these two classes of tasks and to sketch a theory rationalizing their interrelation.

The first section of the chapter reviews an approach to explaining dissociations developed within the domain of laboratory memory tasks. This approach is based on Tulving’s (1983) ideas of the encoding/retrieval paradigm and the encoding specificity principle. These ideas are compared to similar notions from other domains, and the general heading of transfer-appropriate processing is used to refer to this class of ideas. We argue that the notion of transfer-appropriate processing permits an understanding of dissociations between explicit and implicit measures of retention. The second section briefly reviews dissociations between explicit and implicit measures of retention, as a function of both subject variables (e.g., amnesia produced by brain injury) and independent variables under experimental control (e.g., the levels of processing manipulation). The third section considers the standard explanations of functional dissociations between measures of retention in terms of differing memory systems, particularly the episodic/semantic distinction and the declarative/procedural distinction. Criticisms of these approaches are also briefly described. The fourth section is devoted to spelling out an alternative theory that, in many ways, embodies the notion of encoding specificity to explain the dissociations between explicit and implicit retention. The fifth section of the chapter is aimed at specifying these ideas better and providing further evidence about their validity. The sixth and final section addresses problems of the transfer-appropriate processing approach and suggests future research. The chapter is capped by a few concluding comments on the issues raised.

RETRIEVAL PROCESSES AND ENCODING SPECIFICITY

At the risk of considerable oversimplification, Endel Tulving’s career can be marked by three primary lines of contribution. Although these overlap, one can point to the decade of the 1960s as concerned with the organization of memory, particularly subjective organization in multitrial free recall; to the 1970s as concerned with the effectiveness of retrieval cues and with recall/recognition comparisons; and to the 1980s with the issue of whether or not human memory is subserved by distinct systems. Of course, this division of Tulving’s career into phases is imperfect, because the seed for the major issue of each decade was planted in the prior one. Thus concern with retrieval cues began in the 1960s (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966) and with memory systems in the 1970s (Tulving, 1972). Nonetheless, the division proves useful in identifying the main thrust of research for the decade. The basic argument in the first three sections of this chapter maintains that Tulving uncovered important truths about memory in the 1970s—the encoding specificity decade—and that these ideas also work to explain the data taken as evidence for separate memory systems—functional dissociations among measures of retention (Roediger, 1984). These cryptic remarks are fleshed out later.

Tulving and Pearlstone (1966) showed that category names could serve as excellent retrieval cues in aiding recall of words belonging to semantic categories, relative to performance under free recall conditions. The advantage of cued to free recall surpassed 200% in some of their conditions, which dramatizes the necessity for distinguishing between the information available in memory (what is stored) and the information accessible on a test (what can be retrieved under a particular set of test conditions). The quest to know what information a person has stored in memory and how it is organized will always founder on the fact that any procedure to assess these issues will only reveal what a person knows under a particular set of retrieval conditions. Thus theories of cognitive structure must always specify a set of retrieval conditions operating during testing (Anderson, 1978).

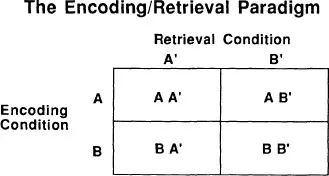

After Tulving and Pearlstone’s (1966) impressive demonstration, interest grew in the factors that caused retrieval cues to be effective (e.g., Thomson & Tulving, 1970; Tulving & Osler, 1968). Numerous experiments were conducted to determine the necessary relation between retrieval cues and stored experiences for successful recollection. The general principle that emerged from numerous experiments came to be known as the encoding specificity principle (or hypothesis): “… recollection of an event, or a certain aspect of it, occurs if and only if properties of the trace of the event are sufficiently similar to the retrieval information” provided in the retrieval cues (Tulving, 1983). Many lines of evidence can be provided to support this assertion, but the most convincing conforms to the encoding/retrieval paradigm shown in Fig. 1.1 here. An experiment using the encoding/retrieval paradigm incorporates conditions in which both encoding and retrieval conditions are manipulated orthogonally. Usually experimenters wish to vary the similarity between encoding and retrieval conditions, a property illustrated by letters in Fig. 1.1. Encoding conditions A and B are crossed with retrieval conditions A’ and B’, which are similar to encoding conditions A and B, respectively. If the encoding specificity principle holds, performance in conditions A–A’ and B–B’ (where encoding and test conditions match) should be better than in conditions A–B’ and B–A’ in which the encoding and retrieval conditions match less well. Numerous experiments have revealed such effects (see Tulving, 1983, pp. 226–238, for 14 examples), so discussion here is limited to a single case that illustrates the point.

FIG. 1.1. The encoding/retrieval paradigm. Minimally, two encoding conditions (A and B) are crossed with two retrieval conditions (A′ and B′). Retention should be enhanced in conditions represented by cells in which the best match exists between study and test conditions (AA′, BB′) relative to the other conditions (AB′, BA′). Adapted from Tulving (1983, p. 220).

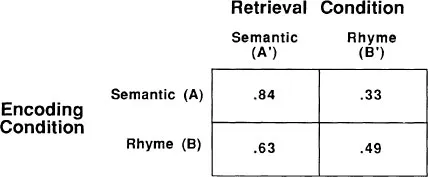

Morris, Bransford, and Franks (1977) reported an experiment dealing with the issue of how manipulations designed to influence the level of processing of studied stimuli affected performance on different types of memory tests. The usual expectation is that deeper, more meaningful processing should aid retention compared to processing that encourages only shallow or superficial coding (Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Craik & Tulving, 1975). Morris et al. (1977, Experiment 1) crossed phonemic (or rhyme) and semantic (meaningful) conditions at both study and test. Subjects studied words such as EAGLE in sentence frames designed to effect either phonemic or semantic encoding (“___rhymes with legal” or “___is a large bird”). The subjects responded yes or no to each statement, and we consider results based on tests of items to which the subjects responded yes during study.

The subjects’ memories were tested in two different ways. Half the subjects were tested on a standard recognition test in which studied words were intermixed with nonstudied words and the task was to identify the studied words. Morris et al. (1977) assumed that the subjects accomplished this task by referring to the meaning of the test words, and thus that one should expect better performance for words encoded semantically rather than phonemically. Indeed, just this pattern was found, as can been seen in the left column of Fig. 1.2. The other test used by Morris et al. was a rhyme recognition test. Subjects were told that the test items would include words that rhymed with the studied words and that they should discriminate these rhyming words from the distractors that did not rhyme with the targets. On this rhyme recognition test the standard levels of processing effect reversed, with phonemic encoding producing better performance than semantic encoding, in general conformity with the encoding specificity principle. The data are shown in the right column of Fig. 1.2. Similar experiments and results were reported by Fisher and Craik (1977) and McDaniel, Friedman, and Bourne (1978), although typically there was no advantage of rhyme encoding on the phonemic test. That is, the standard levels of processing effect disappeared but did not reverse on their versions of phonemic tests.

Several general lessons can be drawn from the research described in this section. First, the encoding/retrieval paradigm is useful for studying the interactive effect of encoding and retrieval conditions in order to investigate the encoding specificity hypothesis. Second, many demonstrations of cross-over interactions or functional dissociations have been found by researchers employing the encoding/retrieval paradigm. Even such robust effects as levels of processing can disappear (Fisher & Craik, 1977; McDaniel et al., 1978) or even reverse (Morris et al., 1977) under the appropriate test conditions. Tulving (1979) used such demonstrations to argue that the notion of levels of processing may be superfluous in describing data from such experiments; rather, such experiments demonstrate the interactive nature of remembering as embodied in the encoding specificity principle, without need for separate “levels” of information to be postulated. Morris et al. (1977) made a similar argument, but cast their view under the rubric of transfer-appropriate processing. The general argument is similar to the encoding specificity principle, but (they argued) more general: study conditions foster good performance on later tests to the extent that the test permits appropriate transfer of the knowledge gained during study (see also Bransford, Franks, Morris, & Stein, 1979; Stein, 1978).1 We return to this argument below as a possible avenue to understanding dissociations between explicit and implicit measures of retention.

FIG. 1.2. Transfer-appropriate processing. Study conditions biased encoding towards rhyme (phonemic) encoding or semantic encoding; test conditions were arranged to tap either one or the other dimension. Data are taken from Morris, Bransford, & Franks (1977, Experiment 1).

DISSOCIATIONS BETWEEN EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT MEASURES OF RETENTION

The main challenge of this chapter is to provide an account of dissociations between explicit and implicit measures of retention as a function of various independent and subject variables. First it is necessary to provide a brief review of such dissociations, but we do so by providing examples of important findings rather than by reviewing the literature exhaustively. Readers can consult recent excellent reviews by Shimamura (1986), Schacter (1987), and Richardson-Klavehn and Bjork (1988) for fuller treatments.

Some form of distinction between explicit and implicit retention is quite old, being honored in the writings of many philosophers (see Schacter, 1987). Even within experimental psychology the distinction dates to Ebbinghaus’s (1885/1964) great book (Roediger, 1985). However, modern interest in the distinction is relatively recent and has its origins in work with amnesic patients. Patients are classified as amnesic when some brain injury renders them seemingly incapable of retaining new experiences; more technically, they suffer a profound anterograde amnesia. Studies of famous cases such as H. M., whose amnesia was due to a temporal lobectomy, and other more typical forms of amnesia (e.g., numerous cases of Korsakoff’s syndrome) led to the conclusion by about 1970 that amnesics were incapable of transferring verbal information from a relatively intact short-term store to a long-term memory (e.g., Baddeley & Warrington, 1970). Researchers were aware that even profound amnesics such as H. M. were capable of learning and retaining motor skills at about the same levels as were normal subjects (e.g., Corkin, 1968), but retention of verbal information in amnesics survived only at very low levels, if at all, after a period of brief distraction following its study.

This picture of retention in amnesics began to change around 1970 because of reports by Warrington and Weiskrantz (1968, 1970) indicating that amnesics occasionally showed normal levels of performance on certain verbal tests. These early claims were, of course, disputed and discussed because they seemed inconsistent with so much prior literature and thinking. But many more recent studies have confirmed Warrington and Weiskrantz’s findings and have indicated the variables responsible for their occurrence. Their prototypic experimental study is considered here.

Warrington and Weiskrantz (1970, Experiment 2) presented four amnesic patients (three Korsakoffs and one with a temporal lobectomy) words to remember and then assessed their retention on four tests. Sixteen control patients without brain damage were similarly test...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Participants

- Biographical Sketch

- Part I: Encoding and Retrieval Processes

- Part II: Neuropsychology

- Part III: Classification Systems for Memory

- Part IV: Consciousness, Emotion, and Memory

- Author Index

- Subject Index