eBook - ePub

Motivation, Emotion, and Goal Direction in Neural Networks

- 468 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Motivation, Emotion, and Goal Direction in Neural Networks

About this book

The articles gathered in this volume represent examples of a unique approach to the study of mental phenomena: a blend of theory and experiment, informed not just by easily measurable laboratory data but also by human introspection. Subjects such as approach and avoidance, desire and fear, and novelty and habit are studied as natural events that may not exactly correspond to, but at least correlate with, some (known or unknown) electrical and chemical events in the brain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Motivation, Emotion, and Goal Direction in Neural Networks by Daniel S. Levine,Samuel J. Leven in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

THEORIES OF PAVLOVIAN CONDITIONING

1 | Propagation Controls for True Pavlovian Conditioning |

International Business Machines Corporation

University of South Florida

The architectures and mechanisms of learning are becoming more important to the design of machines that will work on more complex and open problems. Biological systems are being studied as the prior art for such designs, but several controversies still remain about the role of habituation in conditioning, the generation of responses that cannot be defined a priori, and the reality of a new computational rubric within actual nervous systems. As a bridge between recent discoveries in both computer and neural sciences, this work presents a quantitative model of habituation and sensitization, most notably found in the mollusc Aplysia, but as part of a larger dynamics analogous to connectionism’s computation of energy contours and their control by simulated annealing. Pavlovian conditioning is modeled as the control of propagation through laterally connected reflex arcs. These arcs pass through two layers: The alpha layer computes temporal contingencies according to activity-dependent sensitization and habituation. The beta layer stores an energy contour similar to a dominant focus. Feeding forward to the beta layer, the alpha layer controls both stimulus propagation through the contour and the formation of the contour itself by potentiation. Negative feedback from the beta layer provides the control function analogous to simulated annealing. This model demonstrated habituation, classical conditioning, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. Both alpha and beta conditioning were produced, but, in contrast to alpha conditioning, the beta response learning curve showed initial positive acceleration and much higher final asymptote. Extinction and spontaneous recovery were demonstrated as properties of habituation. The model’s limitations are considered for the future elaboration of a more complete and general mechanics.

CROSSDISCIPLINARY BRIDGES

The resurgence of neural modeling within recent years is the resurgence of a very simple idea: Study extant neural systems as the prior art for machine design. Although our understanding of learning is still at the forefront of research, there is an enormous prospect for using this knowledge for the design of adaptive systems. This is especially true of learning when more precisely defined as “conditioning,” the strategy by which animals infer the causal structure of their environment for competitive survival in real time and real space. Understanding how animals make such inferences will allow the design of machines that are able to do the same.

Motivation, emotion, and goal direction are integral parts of learning, making neural systems much more intricate than learning simple association matrixes. The past several decades of neuroscience have provided insight into both the function and physiology of how attention, drive, incentive, and instinct are related to learning; yet several principles of design remain underrepresented in the neural network literature. For instance, Premack’s Principle (1962) refutes any notion of specialized reinforcers; all stimuli have the potential to reinforce each other. On the other hand, some associations are more difficult to learn than others; Seligman’s concept of preparedness (1970) indicates a continuum of instinctive reflexes and learned ones. Such a continuum is necessary for survival.

Our model incorporates such principles and moreover, demonstrates motivation as a set of control processes. Motivation is a determinant in stimulus attention and the initial storage of memory, but, in addition, motivation and emotion are important components in the expression of memory. We use the phenomenon of spontaneous recovery from extinction to show how such controls determine whether or not a learned memory is in fact expressed.

Learning research has many strong traditions across many different fields, but, for further progress in neural modeling of learning, stronger bridges must be built across the fields of information and neural sciences. In the conclusions of Sejnowski, Koch, and Churchland (1988), “we expect future brain models to be intermediate types that combine the advantages of both realistic and simplifying models” (p. 1305). Realistic models include as much detail as possible; simplifying models abstract the important principles. Our model presents one such bridge between the rubric of gradient descent, energy contours, and simulated annealing and the known facts of neuroscience. Simplifying models too easily lose touch with biology; thus, our bias is more strongly toward neuroscience. We do not adopt any computation simply for the sake of its correct function. On the other hand, realistic models by themselves can fail to describe the overall functions of a system. This is why we use the mechanics of energy contours (Hopfield, 1982) and simulated annealing (Kirkpatrick, Gelatt, & Vecchi, 1983) to understand conditioning across its many levels of investigation: physiology, architecture, and behavior.

As an intermediate between realistic and simplifying types, our model is not of any particular neural system. Every component is based not so much on any specific data but on known neuroscientific fact, law, or principle. Just as principles are validated across a range of systems, we present a general model of Pavlovian conditioning based on the larger body of learning and motivational theory. We hope this establishes a bridge between the detailed mechanisms described in the present section of this book and the global brain dynamics to be described in the next section. Our full model will have implications for cerebrocortical processing and simultaneous input for potentiation, but we begin with an invertebrate, a “soft underbelly” to establish the physiological detail of simple conditioning.

BACKGROUND MODELS

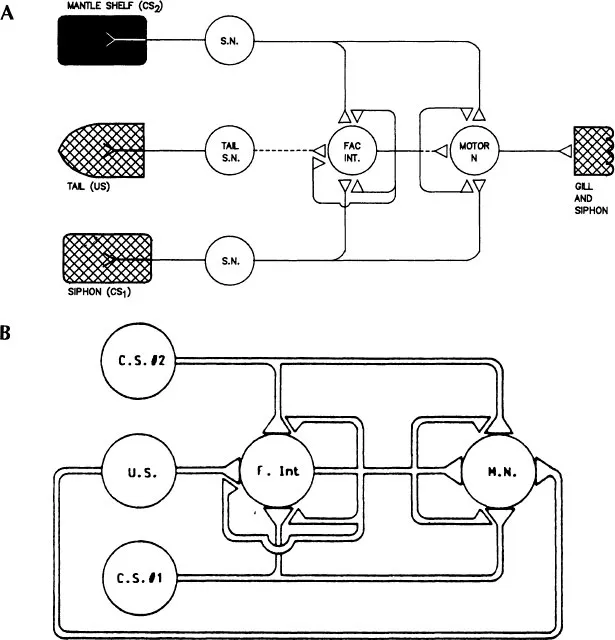

Aplysia, a gastropod mollusc, has been a major biological system in the search for the engram. Several decades of work have elucidated the elemental mechanisms of habituation and sensitization and how these mechanisms operate in simple conditioning. Fig. 1.1A shows one of the more complete models to date as proposed by Hawkins and Kandel (1984). Tactile stimulation to the siphon or mantle shelf represents a conditioned stimulus (CS), which activates the appropriate sensory neuron and its monosynaptic connection to the motor neuron. Habituation, the most elemental form of learning, is an intrinsic governor of the sensory neuron terminals; through some mechanism for calcium channel dysfunction, habituation decreases the efficacy of the sensory neuron synapse as a function of repeated low-intensity stimulation. Calcium is required for the release of neurotransmitter; thus, calcium channel dysfunction decreases the synapse’s efficacy.

However, if a CS is followed by an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), the UCS activates a facilitatory interneuron responsible for presynaptic modulation of the sensory-motor neuron synapse. In contrast to habituation, this extrinsic governor is called activity-dependent sensitization. Sensitization by the UCS is dependent on just-prior activity within the CS pathway; therefore, repeated presentation of a CS1 followed by the UCS will selectively increase the motor neuron’s response to only the predictive CS1 (not the CS2). Such a mechanism has been implemented in simplifying neural networks, such as Sutton and Barto’s (1981) use of an eligibility trace, and in realistic models of calcium influx and buffering in Aplysia (Byrne, Gingrich, & Baxter, 1989). This calcium trace mechanism also produces the interstimulus-interval (ISI) effect at the behavioral level of conditioning; there is some delay in the accumulation of intracellular calcium caused by the CS, and, because UCS facilitation is amplified by intracellular calcium, conditioning is best when the CS is presented just before the UCS. Simultaneous stimuli produce poor conditioning.

FIG. 1.1A. Conditioning pathways in Aplysia (from Hawkins & Kandel, 1984). The sensory neurons (S.N.) of conditionable stimuli (CS1 and CS2) make monosynaptic connections with the motor neuron. All stimuli, including the unconditioned stimulus (US), excite a facilitatory interneuron (FAC.INT.) that presynaptically modulates all sensory connections, both to the motor neuron and to itself. Furthermore, because the CSs are already connected to the motor neuron, and this is the only response in the associative repertoire, this circuit is capable only of alpha conditioning; pairing-specific enhancement produces a larger response in the motor neuron to which it is already connected, not a new response. FIG. 1.1B. Circuit for computational model of conditioning in Aplysia (from Gluck & Thompson, 1987). This circuit is identical to the Hawkins-Kandel configuration, but with the addition of a direct US connection to the motor neuron. This addition allows the facilitatory neuron to become refractory after CS activation, for blocking, but still allows an unconditioned response to the US. Again this allows only alpha conditioning; there is only one response in the repertoire and all stimuli are innately connected to its motor neuron. (Both reprinted by permission of American Psychological Association.)

Kandel’s earlier representations of this circuit showed only the feedforward connections of the facilitatory interneuron to the sensory-motor neuron synapses, but when Hawkins and Kandel argued that these elemental mechanisms form an alphabet for the construction of several conditioning effects, they added feedback. In order to explain such phenomena as secondary reinforcement, they added sensory-facilitatory neuron synapses and feedback modulation of the facilitatory neuron to synapses on itself. In this manner, CS1 can also access the facilitatory machinery to act like a UCS during secondary reinforcement of the CS2. Hawkins and Kandel’s qualitative speculation about this alphabet was followed by Gluck and Thompson’s (1987) quantitative model. Fig. 1.1B shows their model, identical to that of Hawkins and Kandel except for additional stimulus symmetry, a monosynaptic connection from every stimulus pathway (including the UCS) to the motor neuron.

Our model is highly indebted to the Hawkins and Kandel consolidation, but there are several remaining concerns with Aplysia models in general that we hope to resolve. First, we will incorporate complete stimulus symmetry according to Premack’s principle (Premack, 1962). Any stimulus can reinforce any other stimulus; definitions of the CS and UCS cannot be a priori established by asymmetrical circuit design. Hawkins also included such complete symmetry in his most recent model (Hawkins, 1989). Second, Aplysia models demonstrate only alpha conditioning, the enlargement of an already established response. In contrast, true Pavlovian conditioning does not assume an a priori connection between the CS and its eventual conditioned response (CR). As illustrated by a bell coming to elicit salivation in Pavlov’s dogs, true Pavlovian conditioning can establish a CR not initially elicited by the CS. Third, there is still a need to bridge the detailed physiology of learning in Aplysia with the abstract analogies of energy contours and simulated annealing, central ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- PART I. THEORIES OF PAVLOVIAN CONDITIONING

- PART II. COMPLEX MOTIVATIONAL-COGNITIVE CIRCUITS IN THE BRAIN

- PART III. APPLICATIONS OF GOAL DIRECTION IN ARTIFICIAL NEURAL SYSTEMS

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX