- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Local History in England

About this book

Considered to be the classic introduction to the subject, this third edition has been carefully revised and updated to take account of the developments in the subject, and includes an extensive newly compiled bibliography and twice the number of illustrations as in previous editions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Local History in England by W. G. Hoskins,David Hey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Local Historian Today

This book is intended to be a book of advice and guidance to all those who are studying local history and topography anywhere in England, especially those who are hoping to produce their own history of a particular place. There must be thousands of local historians passionately interested in one place—a parish, a village, or a small town. They now form a multitude where once they were a select few.

The local historian, wherever he or she may be, constantly comes up against problems and difficulties in discovering the sources, in using them aright, or in extracting their real meaning; or he* may come up against important periods or problems for which there appear to be no sources at all. All local historians will know these formidable obstacles that suddenly appear in their path, and will also know how often one looks in vain for an answer, for some guidance how to proceed. There is no book to go to.

I have tried to write such a book here, though I would not claim to anticipate all the problems that may arise in all the varied communities of England and certainly not all the answers. However, I have had more than fifty years' experience of studying and writing the history of counties, of towns, of villages, and parishes, and even of farms and streets, and what I have learnt may be of some use to others. I have broadcast often on a variety of approaches to local history and offered advice to unseen audiences; and I have received hundreds of letters which raised difficulties that were

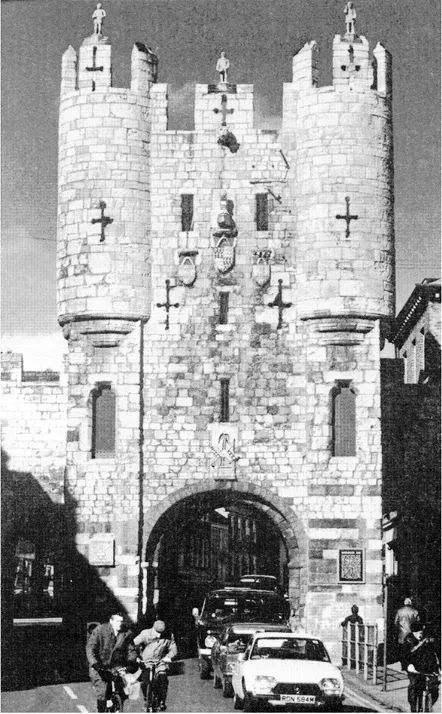

1.1 Mícklegate Bar, York

York's rich history goes back over 1,900 years to the founding of the Roman fort of Eboracum in ad 71-74. The Roman defences surrounding the legionary fortress and the colonia were strengthened and heightened by each successive group of invaders—Angles, Vikings and Normans—until they achieved their present form during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. No other English city has such a remarkable set of walls, towers and bars. Micklegate was the Viking 'great street', the principal highway from the south and west that curved down the hill to the commercial heart of Joruik. Until 1863 the Ouse could be crossed only this way.

Micklegate Bar preserves its Norman arch, but the upper parts were redesigned in the fourteenth century. Until the late 1820s the entrance was protected by a barbican, which stretched about as far as the front car in the photograph. Micklegate Bar was the scene of ceremonial receptions and the place where the heads of executed traitors were displayed on many occasions in the Middle Ages.

York's rich history goes back over 1,900 years to the founding of the Roman fort of Eboracum in ad 71-74. The Roman defences surrounding the legionary fortress and the colonia were strengthened and heightened by each successive group of invaders—Angles, Vikings and Normans—until they achieved their present form during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. No other English city has such a remarkable set of walls, towers and bars. Micklegate was the Viking 'great street', the principal highway from the south and west that curved down the hill to the commercial heart of Joruik. Until 1863 the Ouse could be crossed only this way.

Micklegate Bar preserves its Norman arch, but the upper parts were redesigned in the fourteenth century. Until the late 1820s the entrance was protected by a barbican, which stretched about as far as the front car in the photograph. Micklegate Bar was the scene of ceremonial receptions and the place where the heads of executed traitors were displayed on many occasions in the Middle Ages.

usually of general application and did not relate to one place. Lectures in various parts of England, followed by innumerable questions, have also made me aware of what are the commonest difficulties in the path of those who are devoting themselves to the history of some chosen and beloved place. The time has come to embody this experience, such as it is, in a book of short compass, for I want it to reach all those in need of help and guidance wherever they may be.

In this book I shall be concerned with problems of techniques and methods. I shall discuss also what themes the local historian ought to bear in mind; how he should organise his material so that it presents a coherent whole rather than a miscellaneous collection of facts; how he should tackle and interpret certain particularly difficult but inescapable sources such as Domesday Book; and how he should read maps as historical documents so that they can be made to yield information about dark periods of local history for which there may be no other source. For those particularly interested in town history I have tried to suggest the methods by which they may study the physical growth of a town rather than its growth as an institution: in other words, the town as a town rather than as a borough, for there is plenty of guidance already on the latter aspect. I have also devoted a chapter to the social and economic history of towns. The study of urban history has recently made immense strides in this country and now has its own journal, The Urban History Yearbook, which every local historian with a special interest in towns should read.

I also want to give advice on fieldwork in local history. The great scientist Humboldt said that no chemist ought to be afraid to get his hands wet. For the same reasons, no historian—certainly no local historian—ought to be afraid to get his feet wet. I attach so much importance to the visual evidence revealed by fieldwork that I have devoted two chapters to it in this book.* First, on how to study the physical markings on the landscape of the parish and how to interpret what one sees. And second, how to make a record of the buildings of one's chosen territory, for such a survey seems to me to lie very near the heart of the subject of local history: an exact recording of the houses of former inhabitants of a parish or town and of the places where they worked—the early workshops, the waterpower factories, engine-houses, lead-mills, or whatever the characteristic local industry may have been. To ignore all this visible evidence because it is not supported by some document in the Public Record Office or the parish chest seems to me an extraordinarily one-eyed view of history. Some of the best documented local histories betray not the slightest sign that the author has looked over the hedges of his chosen place, or walked its boundaries, or explored its streets, or noticed its buildings and what they mean in terms of the history he is trying to write.

This book is not written for the specialist or the professional historian. It is written for the great army of amateurs in this field. Even there I am conscious of talking to readers with very different levels of accomplishment and training, and that some of my advice will be, for some readers at least, superfluous or elementary. I hope they will forgive this necessary approach to the subject and find hints elsewhere in the book that will be of help to them. Not that I think there is only one way of doing these things and that I alone know it. There are many different ways of studying and writing local history. But some ways are to my mind more profitable than others, and I think that local historians ought to make an effort to improve their technique and their knowledge of the sources, however long they have been at it.

On this subject of amateur and professional, there are some pregnant remarks by Samuel Butler: 'There is no excuse for amateur work being bad. Amateurs often excuse their shortcomings on the ground that they are not professional: the professional could plead with greater justice that he is not an amateur.' There is a great deal of truth in this. We always do best those things we are not doing for money, or that we are not obliged to do. The amateur—I hope it is clear that I am using the word in its original good sense—has made a large contribution to English local history in the past, and there is still plenty of room for him (or her) in this vast and still largely unexplored field. Indeed, it was amateurs who founded the study of local history and topography in this country, and who nourished it for over four hundred years. One could truthfully say that the professional historian only entered this field when The Victoria History of the Counties of England was founded in the year 1899. There will be plenty of room for the amateur for generations to come. He brings to the subject a zest and a freshness, and a deep affection, which the overworked professional can rarely achieve. But he must also take his hobby seriously and go on enlarging his horizon and improving his technique to the end of his days.

Primarily I regard the study of local history and topography as a hobby that gives a great deal of pleasure to a great number of people, and I think it wrong to make it intimidating, to warn them off because they may not have the training of the professional historian. It is a means of enjoyment and a way of enlarging one's consciousness of the external world, and even (I am sure) of the internal world. To acquire an abiding 'sense of the past', to live with it daily and to understand its values, is no small thing in the world as we find it today. But the better informed and the more scrupulous the local historian is about the truth of past life, the more enjoyment he will get from his chosen hobby. Inaccurate information is not only false: it is boring and fundamentally unsatisfying. The local historian must strive to be as faithful to the truth as any other kind of historian, and it is well within his powers to be so.

Local Historians of all Kinds

Each year as the evenings grow longer and darker some few thousands of men and women, even a few schoolboys here and there, feel the renewed impulse to turn inwards after the outward activity of the spring and summer. They take out once more their notes on the history of their own parish or village, less often their town (for this is a large undertaking), to browse over again, to add a detail here and there, and to wonder how to go on, where to look next for more material, and how to find the answers to questions that have been bothering them winter after winter.

For years perhaps they have been gathering these notes from books in the nearest library, or records in the parish chest, perhaps from central records somewhere in London, and from conversations with people of an older generation who have known an entirely different world. They have set down their notes in exercise books, filling page after page with the past life of their own small piece of country. Nothing is too trivial to them, for they possess that poetic insight which comes from an acute sense of the past, a sense that is very much more general among country people than among townsmen, above all in the remoter provinces of England and Wales. Not that towns have less history: far from it. Every street in an old town is rich in its own peculiar history. But the conditions of life in large towns do not favour generally the contemplative life, and without some leisure for contemplation and reflection this sense of the past cannot be nourished and will not grow.

But whether in town or in country parish these men and women feel an unquenchable desire to know all there is to be known about the past of the small piece of England in which they were born or which they have come to love. They study the map of their chosen place and wonder what secrets it contains if only they could find the key; what history lies in the shape of its boundaries and of its fields and their names; or in the way the streets run and the names they have; or the situation of the farmsteads, their plans and their names, and whether the pattern of the roads and lanes has any meaning which can be unravelled. They study the parish register, turning its fragile leaves crammed with faded brown writing which perhaps they can only partly read. They study the monuments in the church and copy the inscriptions, not forgetting the older headstones in the churchyard and the worn floor-slabs in nave and chancel.

The growing and almost insatiable demand for guidance in the study and writing of local history has been a feature of adult education classes, especially since 1945. There is, in fact, a shortage of teachers competent to take such classes. It is difficult to explain this remarkable growth of interest in local history. One cannot attribute it even to television, which is partly responsible at least for the equally marked growth in the amateur study of archaeology in this country (and also for much amateur damage to our antiquities). It may be that with the growing complexity of life, and the growth in size of every organisation with which we have to deal nowadays, not to mention the fact that so much of the past is visibly perishing before our eyes, more and more people have been led to take an interest in a particular place and to wish to find out all about it. Some shallow-brained theorists would doubtless call this 'escapism', but the fact is that we are not born internationalists and there comes a time when the complexity and size of modern problems leave us cold. We belong to a particular place and the bigger and more incomprehensible the modern world grows the more will people turn to study something of which they can grasp the scale and in which they can find a personal and individual meaning.

In this book I exclude prehistoric archaeology altogether. This is a distinct branch of knowledge with techniques of its own that require a specialised training for their use. This is not to say that prehistoric archaeology should not interest the local historian, for in some parts of England, for example Cornwall or the Cotswolds or Wiltshire, the history of a given parish may stretch far back into prehistoric times and one cannot separate the history from the prehistory. Christopher Taylor's book, Dorset: The Making of the English Landscape (Hodder & Stoughton, 1970) was a remarkable analysis of the extent to which prehistory and the Roman period underlie our modern villages and their fields.

On quite another theme, the Devon Federation of Women's Institutes made a massive survey of the field-names of the county between 1964 and 1970. The coverage was not complete: about half the parishes were completely covered and another sixty-eight parishes in part. This was due to the fact that not every parish possesses a Women's Institute. One parish alone had some two thousand field-names. In fifty-two parishes there was also a complete coverage of the field-names from the tithe maps, and in another ninety-five a partial coverage. In Norfolk the County Federation has compiled a collection of reminiscences of rural life from about 1890 onwards, bringing together much recent local history which would otherwise have perished without anything in writing. Not all human activity and thinking is enshrined in official records (fortunately), and it has to be gathered in other ways.

The Training of the Local Historian

Anyone who attempts to study and to write the history of a chosen place, whether a town or a country parish or perhaps a whole region, must clearly possess a wide range of historical knowledge. Even if there is no prehistory to cope with, and even if no Romano-British history is involved, one will still require a more or less detailed knowledge of every kind of history- political, ecclesiastical, social, economic, military, and yet other kinds—extending over a period of perhaps 1,500 years, if one is aiming to write the history of a place from beginning to end. I shall suggest later that this is by no means the only kind of local history that one can write. But, assuming that this is the aim, the amount of historical knowledge required may seem intimidating at first.

It need not be so. Obviously a basic knowledge of English history is required. One should have a good grasp of national history into which one can fit and explain a great deal of what is happening locally. But there is no need to carry this encyclopaedic knowledge in one's head. It is often sufficient to know what books to go to for the best guidance and for the best account of a given subject; and one need not, and indeed cannot, anticipate all the books one may have to consult in dealing with the local history of any place.

R. B. Pugh, in How to Write a Parish History (Allen & Unwin, 1954) has said that a local historian must know Latin and must be able to read the old handwriting in which most of his sources will be written. This is unnecessarily discouraging advice. A great deal of local history can be completely studied and written up without any knowledge of Latin or palaeography. A knowledge of Latin may present almost insuperable difficulties to those who have not acquired a basis at school If you are obliged to use records written in Latin you may have to depend on some friend who has the necessary knowledge; and there are few local historians so isolated and benighted that they cannot call upon such a friend from time to time. One should say at this point that the local archivist cannot be expected to act in this capacity. He or she is much too busy with routine duties to act as a translator of documents, though they are always ready to give help over particular words or phrases. But it would be wrong to worry the local archivist on a larger scale than this and one should look elsewhere for help.

Similarly, one should not go to the local archivist if one is totally ignorant of palaeography. Much can be done by the local historian to teach himself this knowledge. He will find, if he begins (as I recommend in the next chapter) at the more modern period and works backwards from this point, from known handwriting into the relatively unknown, he will succeed in teaching himself how to read most of the documents ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1 THE LOCAL HISTORIAN TODAY

- 2 ENGLISH LOCAL HISTORIANS

- 3 THE OLD COMMUNITY

- 4 PARISH, MANOR, AND LAND

- 5 CHURCH, CHAPEL, AND SCHOOL

- 6 TOWNS: TOPOGRAPHY

- 7 TOWNS: SOCIAL AND ECONOMICAL HISTORY

- 8 FIELDWORK: THE LANDSCAPE

- 9 FIELDWORK: BUILDINGS

- 10 HEALTH, DISEASE, AND POPULATION

- 11 THE HOMES OF FAMILY NAMES

- 12 SOME SPECIAL TASKS

- 13 WRITING AND PUBLISHING

- APPENDIX I: The ranking of provincial towns 1334-1861

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX