- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Illegal Leisure

About this book

Illegal Leisure offers a unique insight into the role drug use now plays in British youth culture. The authors present the results of a five year longitudinal study into young people and drug taking. They argue that drugs are no longer used as a form of rebellious behaviour, but have been subsumed into wider, acceptable leisure activities. The new generation of drug user can no longer be seen as mad or bad or from subcultural worlds - they are ordinary and everywhere. Illustrated throughout with interview material, Illegal Leisure shows how drug consumption has become normalised, and provides a well-informed analysis of the current debate.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Why are more young Britons taking drugs?

Competing and confusing explanations

Introduction

In this opening chapter we describe the persuasive evidence that far more young people from all social backgrounds are trying a range of illicit drugs. We also ask why we currently have no satisfactory explanations as to why this social transformation has occurred. Traditional sociological and psychological explanations of 'deviance' in adolescence are found wanting, being increasingly caught out by social change. Unfortunately in the absence of any persuasive, authoritative explanations of this widespread drug taking, lay discourses, constructed through the media, have come to dominate the debate. Fundamental to this 'war on drugs' type discourse are a number of misconceptions. 'Blaming' youth and perceiving drug taking as bad, dangerous and tied to delinquency and crime are all foundation stones of this inadequate explanation.

We must understand how this 'everyday' misconception has arisen since it currently distorts the way adults in general and politicians in particular misrepresent the nature of most young people's drug taking.

Blaming youth

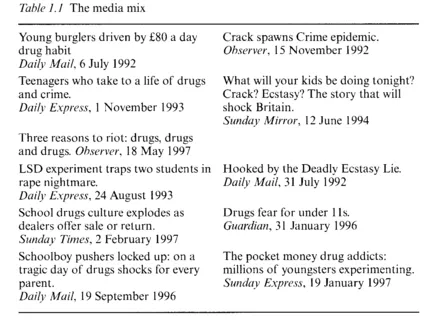

The youth–drugs–crime–danger media mix

The blaming of youth for the ills of society is nothing new. Indeed it is such a well-documented and recurring activity (Cohen, 1973; Pearson, 1983; Goode andBen-Yehuda, 1994) that it probably has important social functions beyond stigmatising particular youthful behaviour. Perhaps blaming the young should be listed as a milestone whereby once uttered, 'the trouble with kids today' (Muncie, 1984) is the password which signals the pathology of a mid-life crisis.

There is little to be gained, however, from blaming adults for blaming youth. The quality and depth of public debate is largely determined by the media. The events and experiences they choose to highlight and elevate, when faced with a barrage of real events and press releases from professional opinion makers be they agents for stars, propagandists for a particular issue or whoever, are significant. This process is extremely complex and often contradictory. How the news is made and its impact on public perception is a subject in its own right (Moores, 1993).

The reason we must start a book reporting on a scientific study of young people in such a 'political' way is quite simple. The key themes in this book – youth, drugs and crime – are the very same topics which have dominated domestic or home affairs in Britain and Northern Ireland through the 1990s. The fourth leg of what is almost an 'official' matrix, a potent mix, which journalists use to frame any youth–crime–drugs story is danger.

We must go back to the 1980s to understand how this process acquired its enormous potency. The early and mid eighties saw the development of what was then an epidemic and is now an endemic, heroin-using population. Around 100,000 young adults from across the UK but notably in the Scottish cities and urban London and north-west England became involved. Most were under-qualified, unemployed and their needs neglected in a period of Thatcher-led economic and social reconstruction. That so many people from the country's poorest marginal communities became heavily involved in heroin was, at the time, regarded as an enormous social problem. Major public policy initiatives were launched and new 'ringfenced' resources were targeted at the problem. Initially the main reason for this was that a real and significant link between regular heroin use and acquisitive crime was established. By and large the criminologists, politicians and the public agreed about this. A series of 'convincing' television documentaries from Panorama and World in Action teams made the case watertight. The drugs-crime link was made (Parker et al., 1988).

The heroin users, particularly the injectors, continued their notoriety with the arrival of AIDS and the evidence, particularly from Scotland, that needle sharing had infected large numbers of young adult injectors. The fear of an HIV/AIDS epidemic, partly transmitted by drug users, sustained drugs stories until the end of the decade but this time emphasising the drugs-danger or indeed drugs-death linkages.

A major public health campaign 'Heroin screws you up' was launched in the late 1980s. It portrayed the heroin user as a junkie, as dirty, sick and dangerous. The junkie lived in the shadows of stairwells in high-rise flats. He would rob you or pressure you into taking heroin and then infect you with death. Significantly this is exactly the image of heroin users that the young people in this study held in their early adolescence. They had watched this portrayal as children and it had been one of the first messages they received about drugs. It probably had more effect on them than on its intended audience of 'at risk' young adults.

The drugs—crime and drugs—danger sides of the mix were in place, having evolved from real events and real processes. There were indeed connections between heroin use and certain sorts of crime and between users' injecting practices and HIV/AIDS. These linkages were sustained and reinforced by a steady flow of stories about both ordinary and extraordinary people who died of drug misuse and/or AIDS.

For just a brief period at the end of the 1980s there was a sense that, if not slain, the dragon had at least been temporarily repelled and drugs stories fell away. Indeed there was space for the media, orchestrated by senior police officers, to create the 'lager louts' (ACPO, 1988). This time the peaceful tranquillity of English shire towns was being destroyed by drunken young men who had jobs and money to spend. They thus had no excuse and their behaviour, in fact borne of long tradition (Tuck, 1989), was temporarily held up as an example of modern moral decay. The towns in question have somehow survived intact!

It was still not school-aged children who figured in the next wave of concern. The media at the end of the 1980s began to run with two other matrix themes. 'Crack' stories from the USA, alongside dire warnings for Europe, of a drug with highly addictive powers leading to a trail of prostitution and drug-driven crime, ran into the new decade (Mott, 1992). That the crack stories spread far more quickly than cocaine use owes much to the power of the media. Crack stories epitomised the ideal news item since drugs-crime and danger were all present in abundance, and indeed if crack cocaine incidence had followed the earlier heroin 'spread' these stories would have been well founded (Parker and Bottomley, 1996).

The other big drugs story which snowballed into the 1990s concerned ecstasy (Henderson, 1997). Despite its extensive use socially and therapeutically in the USA during the 1980s ecstasy only reached public consciousness in the UK near the end of the decade. It was first headlined because the social context for its use, the 'rave' dance scene

in the UK, was initially not just found in night-clubs but in large 'unofficial' parties held secretly in unlicensed venues such as warehouses and aerodromes. Like new age travellers and protesters, young 'ravers' were not acceptable and indeed attracted specific legislation such as the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. It is now illegal to hold an 'unlicensed' rave and police can prevent the movement of people thought to be journeying to such an event (Smith, 1997; Measham et al., 1998).

The more worrying aspect of ecstasy was its role in a series of highly publicised deaths among young 'ravers'. This added youth to the media mix. 'Ravers' were not from the excluded zones where long-term junkies lived. They were younger, of both sexes and from all social classes. They were often articulate and argued their case. They didn't get drunk and fight each other, they danced and hugged each other. The official reply was that ecstasy is a Class A drug, you are breaking the law, committing a crime, and ecstasy is very dangerous. At best, it will lead you into a dependent drugs career and further crime; at worst it will kill you.

The media mix becomes public policy

Over the first half of the nineties blaming youth and reducing complex social issues to simplistic soundbites went beyond media constructions. It became a device of government. It is perhaps unfair to say that this was led by the Home Office since most civil servants at least were not impressed by the policies and behaviour of Michael Howard who was Home Secretary from 1993 until 1997. He leaves a dreadful legacy in much drugs, penal and criminal justice statute and policy. His attack on youth began in the early 1990s but crystallised at the 1993 Conservative Party Conference when he castigated 12–14-year-old 'persistent offenders' for the rising crime rates and sense of insecurity (genuinely) felt by the public. The then Home Secretary had read his tabloids:

We're all sick and tired of reading about young hooligans who've endlessly stolen cars, burgled houses and terrorised communities. We'll set up separate secure centres for 12–14-year-olds who at the moment can't be locked up at all and we must get on, pass the legislation, build these centres and take these thugs off the streets, that's what we've got to do.

The blaming and objectification of young people continued on several fronts. Each summer when public examination results for 16-and 18-year-olds were announced and standards measured by pass grades showed an improvement, the media suggested that the exams must be getting easier. The government response most years was to concur and call a review or enquiry into standards. On the moral front young women from poor communities were accused of getting pregnant to jump public housing waiting lists. Perhaps to discourage sexual activity another Conservative MP called for the censorship of teen magazines like Sugar on the grounds that they provided 'inappropriate' sexual knowledge and encouraged promiscuity.

Although happy to moralise about discipline and punishing the young, the government, through the first half of the 1990s, chose to 'ignore' all the indicators that showed that, for the first time in the UK, a range of 'recreational' drugs was becoming readily available and was being widely used amongst school-aged children, particularly those who were 14–16 years of age. The three key government departments in England, the Department of Health, the Home Office and the Department for Education and Employment, rarely spoke together about this issue and when they did it was often with acrimony, criticising each other's responses. The Department for Education during this very same period withdrew previously earmarked funds to employ school drugs co-ordination officers from local authorities. The Home Office spent large sums of money on a wasteful cosmetic approach to drugs education in Phase I of the Drugs Prevention Initiative. The Department of Health did however commission a piece of research on how to better co-ordinate responses to local drugs problems. Across the Divide (Department of Health, 1994) did at least prompt interagency co-operation, but significantly, in calling for information sharing and partnership between a wide range of professionals and agencies, it made no mention of the divide between young people and their 'professional' elders. There was to be no input from youth itself. The young were defined as objects to be changed not subjects with knowledge, views and ideas about the use of illicit drugs.

As evidence of drug use amongst the young increased and demands for action reached new heights the government decided to repackage its 'strategy'. It too followed and promoted the addition of youth to the matrix of drugs, crime and danger. To admit that a lack of coordination and corporate strategy was part of the drugs problem was an honourable admission and in late 1994 it was decided that the main government departments should have their political heads banged together. John Major claimed that he was the headbanger, 'the drugs menace remains and trends are worrying. Consequently, earlier this year, I ordered a comprehensive review of our domestic drugs strategy. . . . It proposes the most far-reaching action plan ever on drugs' (HMSO, 1994).

That the previously intransigent signed up to the subsequent strategy Tackling Drugs Together, which was, with some small differences, to apply to all the countries of the UK, counts as a major achievement. That a Conservative government should outline a new strategy demanding information sharing, clear objectives, interdepartmental co-operation, and regular monitoring, made this a directive laden with irony. Models of good practice were then, and remain, realities found only at the regional and local level. As a consequence little changed, certainly for central government relating to England, in respect of drugs policy and action until a change of government in mid 1997.

Tackling Drugs Together was important because it allowed central government to shift the responsibility for inertia from its own Whitehall world to the local level where multi-agency teams and partnerships must now wage the 'war on drugs'. The first premise was that young people are 'at risk of drug abuse' and succumb because of peer-group pressure. Secondly drugs are dangerous and a menace. Thirdly, because drug use leads to crime, local communities are themselves at risk, this time from the drug users. 'Media mix' speak had won the day. Youth now joined 'drugs-crime' and 'drugs-danger' and that was official as John Major, the then Prime Minister, made absolutely clear in announcing this strategy in a speech to the Social Market Foundation (9 September 1994). He chose 'yob culture' as the soundbite he wanted the media to headline. So Tackling Drugs Together was about offenders and crime indeed, 'no single crime prevention measure would be more significant than success on the front against drugs'. Drugs and crime were part of the 'yob culture'. The objective must be to 'make a real effort to build an anti-yob culture'.

In short, Tackling Drugs Together, whilst it did support prevention and treatment initiatives, was primarily part of what was the law and order 'two nation' rhetoric of a doomed Conservative government. This discourse was in reality led not by John Major but by Michael Howard. So potent is this approach felt to be in winning votes, hearts and minds that it was hijacked by the Labour Party in opposition and then prioritised as policy upon its election in 1997. The war-on-drugs rhetoric of government was thus maintained but by appointing a drugs Tsar to lead its anti-drugs strategy new ministers were further enabled to distance themselves from taking responsibility for a failing strategy or alternatively presenting a more controversial one.

The essential problem with current government policy on drugs in the UK is that it cannot deal with complexity. It cannot distinguish between types of drugs, types of drug users, diverse reasons for taking drugs and the fact that the drugs-crime and drugs-danger relationships are both real and illusory depending on these other factors. Cannabis may as well be heroin, a weekend amphetamine user a crazed addict, a young woman who gives a friend an ecstasy tablet a drugs baron.

The construction of public policy on such insecure foundations as a media-defined matrix has been totally inappropriate. Youth and the nature of adolescence is deliberately and purposefully misdefined. Throughout the 1990s government has ignored research evidence, civil service and judicial wisdom and, in refusing to recognise that dealing with complexity is a skill required to govern, has failed to understand youth. The Conservative administration of the 1990s took no heed of evidence produced by its own administrators, for instance that transitory 'delinquency' in adolescence can and must be managed differently from persistent long-term offending (see Graham and Bowling, 1995; Hagell and Newburn, 1996). It was no more sophisticated in presenting the country with a drugs strategy. Tackling Drugs Together was knee-deep in simplistic rhetoric which actually instructed resource-starved, local inter-agency partnerships to function on misconceptions. It is some consolation that many local actors recognised this and devised more realistic strategies through local Drugs Action Teams.

The political discourse has an energy of its own. It promotes public fear and anxiety about crime, drugs and youth which in turn it then uses to interfere simplistically, and with apparent public consent, in drugs and criminal justice policy and practice (Hough and Roberts, 1998). This process, because it can barely be challenged, thus spins along reinforcing itself. The UK has distinguished itself from other European administrations, for example in Germany, by politicising drugs, crime and the state of youth. So politically and electorally important is the simplistic rhetoric that a coherent, complex approach to dealing with drug use in a rational way becomes impossible to contemplate, let alone publicly announce. We will return to drugs policy in the final chapter.

How many young Britons take drugs?

There are potentially three types of data sets or associated techniques to help us answer this question: official statistics; social surveys and qualitative studies of young people's lifestyles and leisure activities. The third approach, once so widely and imaginatively used, has, for reasons to be discussed later in the chapter, become less central in respect of understanding youth.

Official statistics

Because they are produced annually official statistics are useful in identifying trends. In relation to drug use the three best official indicators are: the number of drug users known to (mainly) treatment agencies; the number of drugs-related offences known to the police and the criminal justice system and the amounts of controlled drugs seized by Customs and Excise and the police. Unfortunately in terms of identifying drug use amongst adolescents all three indicators are of limited value. The regional 'in-treatment' data bases are dominated by older, problem drug users in treatment. Thus we find substantive information about heroin, methadone, cocaine and poly drug users in their 20s or 30s but understandably far less information about very young 'recreational' drug users. Clearly there is a small number of teenage, hard (primarily heroin and methadone) drug users identified in these data bases but certainly until the late 1990s our main conclusion must be that adolescents in the UK are either not having significant problems with their current drugs of choice or are not being referred to or choosing to visit these heroin-dominated services (e.g. the Community Drugs Team, the Drug Dependency Clinic, etc.). This said there are worrying signs (Parker et al., 1998b) that, at the time of writing, heroin is finding its way into the drug-taking repertoires of a small number of young people, particularly from poorer communities.

Drugs-related incidents reported to the police are not collated and published. Instead only those individuals...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Why are more young Britons taking drugs? competing and confusing explanations

- 2 The North-West Longitudinal Study

- 3 Alcohol: 'our favourite drug'

- 4 Patterns: an overview of drug offers, trying, use and drugs experiences across adolescence

- 5 Pathways: drug abstainers, former triers, current users and those in transition

- 6 Journeys: becoming users of drugs

- 7 Towards the normalisation of recreational drug use

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Illegal Leisure by Judith Aldridge,Fiona Measham,Howard Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.