1.1 Opening

Biofuel cropping systems are shaped by energy and agricultural policies. Following the implementation of ambitious biofuel policies during the first decade of the twenty-first century, biofuel production in many industrial and emerging countries has thrived. After Brazil had shown the way, mainly with its successful Proálcool program for ethanol, the United States of America (USA), Canada, the European Union (EU), Australia, Argentina, China, India, and many other countries developed policies to stimulate domestic biofuel production. The main justifications for the policies, and the support for biofuel producers that was part of the package, were energy security, greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction, rural development, and import substitution.

Introduction of the biofuel support programmes generated widespread criticism. Researchers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and others questioned whether the production of biofuels would really help to reduce GHG emissions and whether the price to be paid was too high. The direct costs included subsidies to farmers to produce biofuel feedstocks, as well as investment subsidies, tax exemptions, and loans, and also indirect costs such as increases in food crop prices and competition for land, water, and farm inputs.

Clearly, it is not self-evident that bioenergy is environmentally (or socioeconomically) superior to fossil energy. Consumers may object to bioenergy products because of concerns about the impacts of their production. Well-to-wheel studies demonstrate that bioenergy systems vary substantially in their reliance on fossil inputs and consequently in their contribution to reduced GHG emissions (e.g., Edwards et al., 2006) – one major rationale for governments promoting these fuels and for consumers using them.

The production of renewable feedstocks can also cause negative impacts. Much attention has been directed to the possible consequences of land-use change, referring to well-documented effects of forest conversion and cropland expansion into previously uncultivated areas, with possible bio-diversity losses, GHG emissions, and degradation of soils and water bodies (e.g., Aubry et al., 2011). Sustainability concerns relating to the feedstock supply systems include direct and indirect social and economic aspects, including land-use conflicts, food security impacts, and human rights violations (Berndes and Smith, 2012).

It is surprising that there is still so much debate about biofuel production. The performance of biofuel chains has been well analysed and reported. Does this not provide sufficient information? Why is the debate so complex and why are satisfactory answers so slow in emerging? After all, biofuel production levels up until now have been quite limited, and the required volumes of feedstocks have been far less than the wastage in food chains or the amounts of food grains fed to livestock. Further, the area of land devoted to the production of feedstocks for biofuels is a small percentage of the total arable land currently in use while further arable areas remain unused.

Part of the answer may be in the quick development of biofuel production, especially in the USA and in the EU. Also, the prospects of further growth may cause concern, while the political and economic support for biofuel production might play a role as well. Finally, feared negative impacts – including the perceived contributions to the strong food-price increases during 2007–2008 – have raised awareness of the possible implications of fully developed biofuel industries.

Consequently, it is valuable to describe and analyse biofuel cropping systems worldwide. This book will do this in a balanced way. We believe there are reasons that past studies have come to such divergent conclusions. Also, we are convinced that it is important to devote time to the description of biofuel production, including the preparation of the land, the cultivation of the crops, and the conversion of biomass into biofuels. Local information (e.g., on soils, cropping systems, farm organisations) helps to explain the diversity and complexity of the conditions under which biomass is produced and converted. It can also shed light on the effectiveness of prevailing biofuel policies and the way these impact biofuel production. Most importantly, this book will help us understand how biofuel production does (or does not) fight poverty, combat hunger, and affect food production and the conservation of forests and biodiversity.

But before we do so, this chapter provides an overview of the issues that have been raised with respect to biofuels (see Section 1.2) and the lessons learned from the analysis of their production (see Section 1.3).

1.2 Points of concern

Not sustainable

In the concept of sustainability, three dimensions can be distinguished: environmental, economic, and social. In different ways, biofuels have been criticised for not being an environmentally sustainable way to reduce GHG emissions. Early studies criticising biofuel chain performance focussed on net energy production (which supposedly would be negative, requiring more energy than could be produced), low energy yields, and high costs. An excellent example of such discussions is given in the paper by Farrell et al. (2006), defending the potential role of corn ethanol in replacing fossil gasoline and reducing GHG emissions, and the array of letters following this paper (and others) in Science later that year.

With respect to GHG emissions, a new dimension was added to the debate when, in 2008, two papers were published on the indirect effects of biofuel production on emissions. Searchinger et al. (2008) and Fargione et al. (2008) demonstrated how changes in land requirements could provoke the conversion of uncultivated areas, thereby causing the release of large amounts of carbon stored in vegetation and soils. Both papers have been highly influential, launching a debate (on land-use change caused by biofuel production) that continues into the second decade of the twenty-first century.

The land-use debate is characterised by three elements that need to be distinguished clearly. First, one needs to determine how much land is devoted to the production of biofuel feedstocks. Second, impacts of the changes on general land use need to be assessed. Most of these effects will occur in regions at (considerable) distance from the place where biofuel crops are cultivated. Therefore, we speak of indirect effects or indirect land-use change (ILUC). Indirect effects usually refer to an expansion of agricultural area, which would be caused by the need to compensate for the loss of land that formerly was used to produce food.

The third element of the land-use debate that needs to be addressed is the amount of carbon that is released from ILUC. This depends not only on the area of land that is converted but also on the amount of carbon that was stored in vegetation and/or soil organic matter and their loss, and is particularly significant in tropical areas.

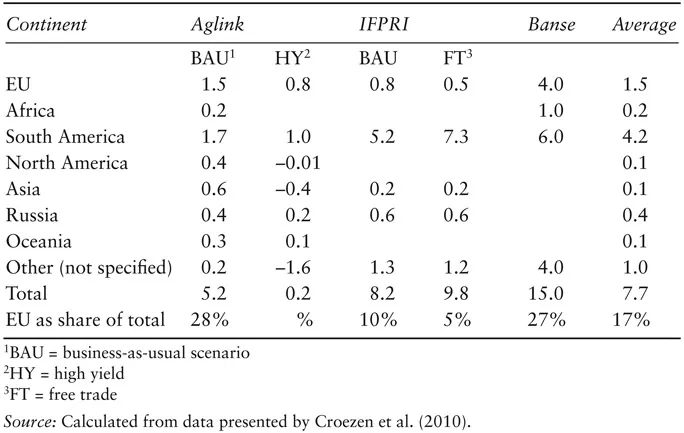

Land-use change in practice is extremely difficult to assess, as biofuel production is presently still a very small part of total global crop production (although in some regions it is significant at the local level). Consider, for example, assessments that have been made of the area that will be needed for the EU to realise its biofuel targets in 2020. Table 1.1 presents an overview of the outcomes of three modelling exercises. The area of land needed to produce biofuel feedstocks for the EU has been estimated from 0.2 to 15 million ha. On average, nearly 8 million ha might be needed in 2020. Most land will be found in South America, as large quantities of sugarcane and soybean will be imported from Brazil, Argentina, and so forth. Domestic production in the EU is expected to cover less than 30% of the extra feedstock requirements.

Crop-yield development is one of the dominant factors determining future land use. Differences between optimistic and less optimistic scenarios (assuming normal or extra yield improvement, depicted by the business as usual [BAU] and high yields [HY] scenarios of the Aglink model, respectively) clearly show the impact of yield improvement. Impacts of trade policies, depicted by two scenarios of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) model, are smaller.

Table 1.1 Land needed to satisfy current EU biofuel targets in 2020 (million ha)

A special point of concern for biofuel feedstock production is the need for agricultural inputs such as fertilisers, water, and agro-chemicals. It is feared that substantial expansion of biofuel production may go at the expense of input availability; this could threaten food production. A major concern is the demand for phosphorus fertiliser – a finite resource that is being mined. Also, water problems may be aggravated by large-scale biofuel crop production, which may cause serious problems in areas that are already drought-prone.

Not profitable

A second point of debate on biofuels is their relative profitability. According to OECD-FAO (2009), biofuel production is increasingly driven by quantitative mandates. These either take the form of blending requirements or minimum biofuel quantities to be used in the national transport sectors. This applies not only to biofuels produced in the USA and the EU but also to countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and many others, including biodiesel development in Brazil. Without mandates, biofuel production is in many cases not profitable.

In many countries, the revenues from fuel excise taxes flow directly into the treasury. In some countries, however, revenues from fuel excise taxes are used to invest in transport infrastructure (OECD, 2008). Some Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries give input subsidies to enhance the use of agricultural inputs. In the EU, farmers using fallow (set aside) land to produce bioenergy feedstocks receive a small subsidy. Other support measures include the reduction in infrastructure costs, capital grants, guaranteed loans, capital allowance schemes, and direct subsidies per unit of biofuel produced (Steenblik, 2007).

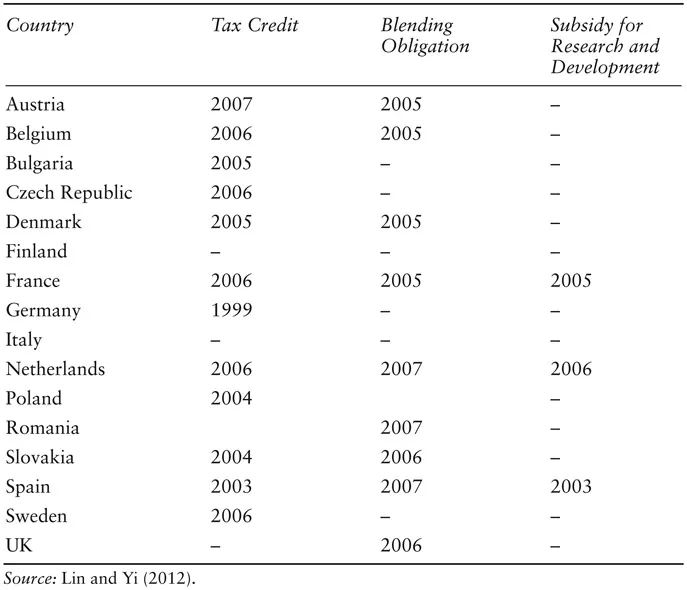

The need for economic support to allow biofuels to compete with their fossil counterparts has been widely criticised; for example, by the OECD (e.g., Steenblik [2007] and OECD-FAO [2009]). Many countries have implemented support measures, including tax credits and subsidies (e.g., for research). Table 1.2 lists policy support measures taken in the EU. Tax exemptions and blending targets are the most common measures. The earliest measures were taken in Germany in 1999 and in Spain in 2003. In most countries, however, biofuel support started in either 2005 or 2006.

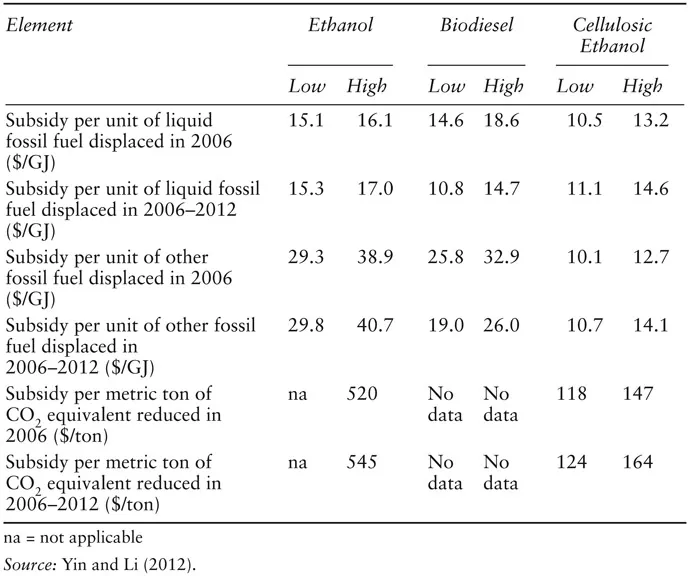

In the USA, measures to support the production and use of biofuels include direct subsidies, blending obligations, research grants, import tariffs, and tax exemptions for biofuel blenders. Support took off before 2006, and an overview of measures is given in Table 1.3. Subsidies have tended to increase since 2006, with the highest support given to the production of first-generation ethanol.

Table 1.2 Introduction of biofuel policy instruments in selected European countries

Table 1.3 Subsidies per unit of biofuels in the USA

Table 1.4 Impact of biofuel support removal on biofuel consumption (billion litres per year)

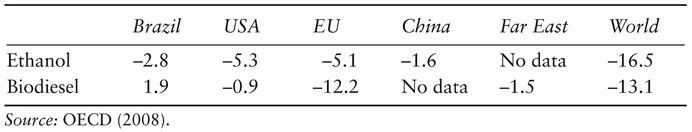

Without financial support, the consumption of biofuels would be less (Table 1.4). Elimination of import tariffs would cause relocation of ethanol production across countries, with increased exports from countries such as Brazil and higher imports in the USA, Canada, and particularly the EU. Some subsidies affect the situation in other countries. For example, biodiesel consumption in Brazil benefits from support measures taken in other countries. Removal of support would reduce biodiesel consumption in Canada by 80% (OECD, 2008).

Competition with food

Financial support for biofuel production will also affect crop feedstock prices. According to OECD-FAO (2007), biofuel production will lead to higher commodity prices, which is of particular concern for net food-importing, developing countries, as well as for the poor in urban populations, and will evoke ongoing debate on the ‘food versus fuel’ issue. Furthermore, they imply higher costs for livestock producers. The perceived role of biofuels in rising food prices has been heavily criticised.

According to OECD (2008), removal of the support for biofuels would lead to price declines for wheat, coarse grains, and oilseeds (all in the 0–10% range), and also for ...