- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Boudica Britannia

About this book

When Roman troops threatened to seize the wealth of the Iceni people, their queen, Boudica, retaliated by inciting a major uprising, allying her tribe with the neighbouring Trinovantes. The ensuing clash is one of the most important - and dramatic - events in the history of Britain, standing testament to what can happen when an insensitive colonial power meets determined resistance from a subjugated people head-on.

In this fascinating account of a legendary figure, Miranda Aldhouse-Green raises questions about female power, colonial oppression, and whether Boudica would be seen today as a freedom fighter, terrorist or martyr.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Boudica Britannia by Miranda Aldhouse-Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Archeologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Boudica’s ancestors

Some dozen Romans of us, and your lord –

The best feather of our wing – have mingled sums

To buy a present for the Emperor;

Which I, the factor for the rest, have done

In France. ’Tis plate of rare device, and jewels

Of rich and exquisite form, their values great

The best feather of our wing – have mingled sums

To buy a present for the Emperor;

Which I, the factor for the rest, have done

In France. ’Tis plate of rare device, and jewels

Of rich and exquisite form, their values great

Shakespeare Cymbeline1

Shakespeare’s British king Cymbeline was none other than Cunobelin, the great British king who ruled a huge swathe of south-east England (including Kent, Essex, Hertfordshire and beyond) between about AD 10 and AD 402. According to Shakespeare, Romans were by no means strangers to the court of Cymbeline, a point that has been made by John Creighton before me.3 Iachimo, the speaker of this passage, is himself an Italian, and he comments on how Romans and Britons are pooling their resources to purchase treasure for the emperor (probably Tiberius). The gift itself, obtained in Gaul, is described as ‘of rare device’, and therefore is perhaps of Gallic make. The importance of the passage for our investigation of Boudica lies in its presentation of Shakespeare’s image of a Britain in which Britons and Romans mingled freely before the official invasion and conquest in AD 43, with regular comings and goings between the island and the continent, although, as the play unfolds, tensions between the members of the two countries erupt into violent antagonism. The enmity between the two nations is eventually reconciled at the end of the drama in the words of the soothsayer, whose speech alludes to the uniting of Caesar’s favours with ‘the radiant Cymbeline’, and of Cymbeline, who says:

… Set we forward; let

A Roman and a British ensign wave

Friendly together. So through Lud’s Town march;

And in the temple of great Jupiter

Our peace we’ll ratify; seal it with feasts. 4

A Roman and a British ensign wave

Friendly together. So through Lud’s Town march;

And in the temple of great Jupiter

Our peace we’ll ratify; seal it with feasts. 4

Archaeological discoveries have lent increasing support to Shakespeare’s view of pre-Roman Britain; a Britain that was familiar with Rome and Roman ways long before the apparently cataclysmic events of the Claudian invasion of AD 43 and a Britain – in the south-east of the country at any rate – that, perhaps from the time of Caesar’s first visits in 55 and 54 BC, was drawing increasingly closer to the Roman orbit. It is with Caesar, therefore, that it is appropriate to begin our exploration of early linkages between Britain and Rome. Without Caesar, it is arguable that Britain would never have become part of the Roman Empire and that the stage upon which the Boudican Rebellion was enacted would never have been set. Having set that stage, the final part of this chapter examines the archaeological evidence for the Iceni and Trinovantes in the first century BC and earlier first century AD.

Julius Caesar’s Britain: a tale of two Britons

But his expedition against Britain was peculiarly remarkable for its daring. He was the first to bring a navy into the Western Ocean and to sail through the Atlantic Sea with an army to make war. The reported size of the island had appeared incredible and it had become a great matter of controversy among writers and scholars, many of whom asserted that the place did not exist at all and that both its name and the reports about it were pure inventions. So, in his attempts to occupy it, Caesar was carrying the Roman empire beyond the limits of the known world. He twice crossed to the island from the coast of Gaul opposite and fought a number of battles in which he did more harm to the enemy than good to his own men; the inhabitants were so poor and wretched that there was nothing worth taking from them. With the final result of the war he was not himself wholly satisfied; nevertheless, before he sailed away from the island, he had taken hostages from the King and had imposed a tribute.

Plutarch Life of Caesar5

The Greek writer Plutarch was born in about AD 46 and died around 120, so he was commenting about events taking place 150 years earlier than his work, and thus beyond living memory. Perhaps the most important part of Plutarch’s narrative on Caesar’s British expeditions concerns attitudes to Britain, a land beyond the world known to the Greeks and Romans, indeed a land that belonged to the realms of myth rather than reality, on the other side of Oceanus (Ocean), the great river perceived by the ancients to encircle the world known to humans.

In introducing the subject of Britain, Caesar himself speaks of it in a manner that, as has been pointed out in recent literature,6 suggests a certain lack of humanitas in terms of its inhabitants:

Most of the tribes living in the interior do not grow grain; they live on milk and meat and wear skins. All the Britons dye their bodies with woad, which produces a blue colour and gives them a wild appearance in battle. They wear their hair long; every other part of the body, except for the upper lip, they shave. Wives are shared between groups of ten or twelve men, especially between brothers and between fathers and sons; but the children of such union are counted as belonging to the man with whom the woman first cohabited. 7

Caesar, then, is deliberately constructing an image of the Britons for the audience at home that polarised them and rendered them as different as possible from the Romans. Caesar was not the only one to record the painted bodies of the islanders: the Augustan poet Ovid referred to them as ‘green-painted’;8 Martial mentions their paint and their blueness,9 and Propertius ‘warns his mistress not to imitate the Britons by painting her face’.10 Herodian’s comment about naked, mud-encrusted and painted Britons11 endorses a classical viewpoint that remained long after Britannia was incorporated into the Roman Empire. This reputation of the ancient British, covered in woad and dressed in animal pelts, was to remain in the British consciousness right up until our own time. In 1911 a drawing by Henry Ford was used to illustrate a book entitled A School History of England, by Fletcher and Kipling, that showed a confrontation between Romans and Britons on the English shore. The Romans are depicted as clean, white, short-haired, fresh-faced young officers, while the Britons are dark with tattoos, with long wild hair. Richard Hingley is right in his surmise that such a picture was probably profoundly influenced by analogies with the British in India, and a perceived resemblance between the Romans/English, on the one hand, and the British/Indians, on the other.12

David Braund13 draws attention to other broadly contemporary literature that similarly treats Britain as a legendary place, notably to a comment by one Philodemus of Gadara (Palestine), writing just before Caesar embarked for the island, an author who doubted the very existence of Britain or the Britons.14 It was important to Caesar that he was the first to do things; he modelled himself on Alexander, who had so dramatically extended the frontiers of the Greek world,15 and retained a sense of rivalry with the Macedonian conqueror’s memory to the time of his death. By mounting expeditions to Britain, Caesar was sending out a powerful message to Rome: that he was afraid of nothing and that he possessed the ability to conquer even mythical territory, thus presenting himself as more than human himself. Even Caesar’s conquest of Gaul was considered by his peers to be a remarkable feat: Cicero was impressed by his contemporary’s colonisation work there, among a previously unknown people.16 So how much more spectacular would be Caesar’s adventures even further to the west, beyond Ocean and the world of humans?

In planning his first reconnaissance of Britain in 55 BC, Caesar himself admitted that he left the expedition rather late in the year. But he justified this initial visit on the grounds that: ‘I knew that in almost all of our campaigns in Gaul our enemies had received reinforcements from the Britons’.17 This is an interesting statement for, on the one hand, Caesar was playing on the idea of Britain as a mythical place beyond the edge of the world but, on the other, he acknowledged that the Gauls were fully aware of the Britons and had close liaisons with them.18 Indeed, two years before the British campaigns, he made the interesting comment that a king of the powerful Gaulish hegemony of the Suessiones (around Soissons, in north-east France) had at one time controlled not only a large part of Gaul but a substantial portion of Britain as well.19 Caesar clearly had a major problem, in his endeavours to pacify Gaul, in the capacity of Gallic agitators to use neighbouring Britain as a refuge, for he refers to this situation on several occasions: for instance, in Book II of his de Bello Gallico he speaks of the rebellious Bellovaci, erstwhile allies of the peaceful Burgundian Aedui, who ‘fled to Britain when they realised what a disaster they had brought upon their country’.20

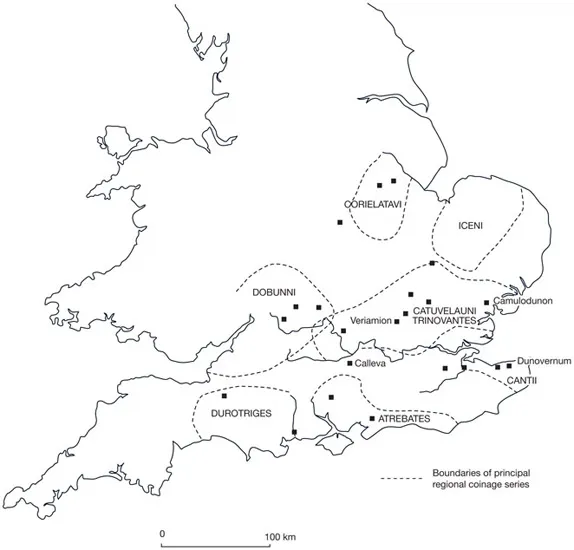

MAP 1 Southern England and Wales in the late Iron Age (the squares plot the sites of ‘urban’ centres – oppida).

Source: Millett 1995.

Two individuals are crucial to our understanding of Caesar and Britain: Commius, a Gaul of the tribe of the Atrebates, and Mandubracius, a British prince of the Trinovantes (see Map 1). Both noblemen played a central role in Caesar’s Britain, that is the area of south-east England closest to the Gallic mainland, and it is arguably their legacy that served to define the Britain inherited by Claudius in AD 43. We first hear of Commius in Book IV of Caesar’s de Bello Gallico, in the context of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Boudica Britannia

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Author's acknowledgements

- Publisher’s acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 Boudica's ancestors

- 2 Conquering a myth: Claudius and Britannia

- 3 Client-kingship in the Roman Empire: Prasutagus and Boudica

- 4 Other Boudicas: ‘big women' in Iron Age Europe

- 5 Femmes fatales: Boudica and Cartimandua

- 6 The role of the Druids in Boudica's Rebellion

- 7 Rape, rebellion and slaughter

- 8 Aftermath: retribution and reconciliation

- 9 The Icenian wolf: legend and legacy

- Epitaph

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates