![]()

Chapter 1

The Brave New Frontier

of Sustainability:

Where are We?

INTRODUCTION

It is often said that ‘development’ as envisioned today is largely a post-Second World War phenomenon that has moved, not necessarily progressed, through various forms and fashions. The 1950s and 1960s were the days of grand development theories all applied at the macro-scale (country, region). The Green Revolution in Asia is such an example based on modernization theory. The grand theories became less fashionable in the 1970s, and the 1980s and 1990s were the age of the ‘micro-intervention’ in development. The boundaries of state intervention and control were rolled back and efforts were instead focused on allowing individuals to help themselves. Terms such as ‘stakeholder’, ‘farmer first’ and ‘participation’ rapidly gained ground. Yet the 1980s saw the rapid expansion of one development theory that successfully managed to combine both macro- and micro-perspectives: sustainable development (SD). It is perhaps hard to appreciate it now, some 20 years or so later, but this may really be said to be different. In SD the individual is seen as central, but one could scale up from that to quite literally the globe. All were involved, no matter where on the globe one lived or what one did for a living. No one is exempt and no one can pass on the responsibility to others; not even to the next generation. Add to this a multi-disciplinary focus encompassing economics, culture, social structures, resource use, etc, and it's not difficult to see how the all-encompassing nature of SD – multi-scale, multi-disciplinary, multi-perspective, multi-definition – has ensured that it is perhaps the ultimate culmination to development theories. Indeed it is much more than the adding together of ‘development’ and ‘sustainability’ (Garcia and Staples, 2000) and at the turn of the century SD has become the dominant paradigm within development. After all, as Bossel (1999) puts it:

There is only one alternative to sustainability: unsustainability.

Put in those stark terms, who wants unsustainable development? SD made the world a place where individuals had a stake, and was not just a matter for the economists and politicians (the traditional view). As a result SD has helped spawn the wide range of ‘direct action’ groups such as those that now protest at meetings of the most industrialized countries.

In this chapter we will explore some of the issues in SD at the turn of the century. The chapter will begin by addressing the contested nature of SD, and the reason why that should occur. It will then proceed to discuss some of the methods used to track progress towards SD, with particular focus on the use of indicators as a device. A commonly expressed central element in all of this is the need for public participation; experts should not solely drive SD. Addressing a wider audience does inevitably mean that one has to work with multiple perspectives on SD. Facilitating such participation and handling multiple perspectives within it require specialized methodologies and skills. Some of these, particularly the adaptation of soft systems methodology (SSM), will be outlined. But participation does not automatically mean painless or easy transition to SD. Indeed, the practice of public participation brings problems, and some of these will be discussed at the end of the chapter.

WHAT IS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT?

Sustainable development has many definitions,1 but perhaps the most commonly quoted within the extensive literature on the subject is:

Development that meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs and aspirations. (WCED, 1987)

This definition arose out of the United Nations-sponsored World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), chaired by the former Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland. Its report, Our Common Future, (WCED, 1987) contains the above definition, and this has been repeated verbatim, or modified to suit specific institutional or individual needs, ever since. It comprises two dimensions: the notion of development (to make better) and sustainability (to maintain). The word ‘sustainable’ is often attached to other human-centred activities such as agriculture, natural resource management, health care provision, urban centres, etc. These are all elements of SD, and are based on the same underlying principle of not compromising the future, and in a sense we can refer to a ‘sustainability movement’. Indeed, the term ‘sustainability’ is often used synonymously with SD.

Like other development approaches, SD is all about an improvement in the human condition, yet unlike many of the others it does not emphasize economic growth or production. The difference from other macro theories of development rests not so much on its focus on people, because they all have that, but more on the underlying philosophy that what is done now to improve the quality of life of people should not degrade the environment (in its widest bio-physical and socio-economic sense) and resources such that future generations are put at a disadvantage. In other words, we (the present) should not cheat the future; improving our lives now should not be at the price of degrading the quality of life of future generations. At the same time, the ‘sustainable’ element to SD does not imply stasis. Human societies cannot remain static, and the aspirations and expectations that comprise a part of ‘needs’ constantly shift (Garcia and Staples, 2000). How all of this has been set out in definitions is a fascinating discussion in itself, with almost every organization involved in SD putting its own spin on the wording and phraseology that reflects its own mission and vision. While this may be exasperating, we agree with Meter (1999) that ‘one of the joys of the sustainability movement is to learn how many different definitions people use of the term sustainability’.

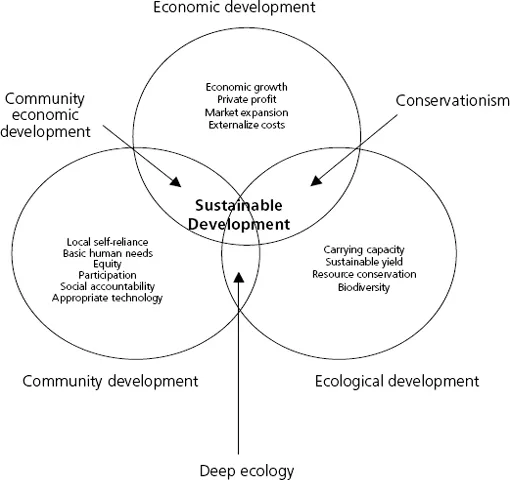

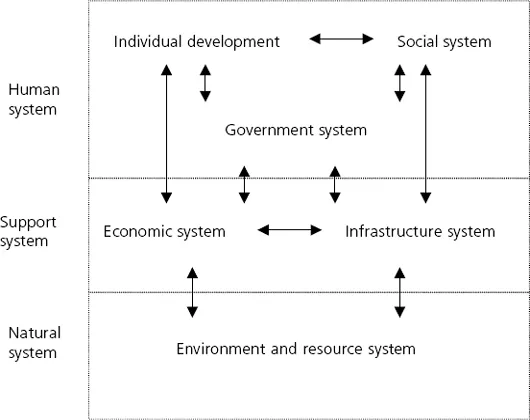

SD is classically portrayed as the interface between environmental, economic and social sustainability (Goodland and Daly, 1996), and the ideas inherent in SD are often presented in visual terms. Indeed, a study of the visual devices used in the literature (SD art) and the ideas behind them could be a fascinating topic for analysis in itself. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 are two forms in which this relationship has been visually presented. In Figure 1.1, perhaps the most common type of presentation of SD, there are three interlocking circles, with SD representing the point where all three overlap. This diagram has had much appeal in the literature, perhaps because of its stress on circularity and non-linear inter-linkage. By way of contrast, in Figure 1.2 the components and relationships are presented in a more mechanistic form, as boxes and arrows respectively. Here we see an emphasis on linear, almost mechanical, linkages.

However, although a desire for ‘improvement’ of the human condition and a concern for future generations (or ‘futurity’) rest as twin pillars at the heart of SD, the detail of what all this implies in practice has been open to much debate. As with all development approaches, one is always left with the basic question as to which people we are talking about. Just who is supposed to be developing sustainably? Where are they in terms of ‘space’ (meaning more than just physical location, but also including socio-cultural dimensions)? Part of this is the ever-present question as to what exactly ‘development’ and ‘improvement’ means to them. Extending this further raises questions as to the timescale involved. How many generations ahead should we consider?

Figure 1.1 The interactions between ecological, economic and social (community) development

As one may guess, answers to all these questions can depend a great deal upon who is asked for an opinion (Meppem and Gill, 1998). Perspective is critical, and as soon as more than one person in included then, by definition, this becomes multiple. Globalization may have helped induce some uniformity in perception and aspiration, but the extent of this is surely debatable, and in any case the likely outcome is a ‘ratcheting up’ of expectation rather than a levelling down (Deb, 1998). Yet SD is all about equity (Templet, 1995), not just in inter-generational terms (‘don't cheat our kids’), but also within the same generation.

Indeed, the very soul of SD is that it is participatory. It is not something that can be imposed by a small minority of technocrats or policy-makers from above. Instead, SD should involve people from the very beginning. This is embodied within Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development:

Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens. Each individual should have . . . [information], and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. (UNCED, 1992; cited in Curwell and Cooper, 1998)

Source: after Bossel, 1999

Figure 1.2 The six key sub-systems of human society and development

Some even see SD as impossible without a parallel emphasis on good governance. Yet while this is laudable, it can be difficult in practice. With the best of intentions, can we really include everyone's views? Do we not inevitably hear those with the most power or those with the loudest voice? The result may be feelings of disenfranchisement, and perhaps the emergence of the direct action groups mentioned earlier.

The lack of a common understanding of SD, beyond very broad mission statements such as that of the WCED, seems to have been a source of frustration for some (de Kruijf and van Vuuren, 1998). At one level, if SD is founded upon a requirement to address the local perspective then it would seem to be unlikely that a global consensus will ever emerge. But can we determine a community's SD without correlations to larger scale, including global, processes (Allenby et al, 1998)? If nothing else, SD is a shared responsibility, and some express a desire to apply some common understanding across similar systems (de Kruijf and van Vuuren, 1998). Whilst appreciating that a system is the outcome of an individual's understanding, multiple perspectives can trip us up if we are not careful. A system is quite literally defined by the person experiencing it, and it will be different to different stakeholders. Solow (1993) has also decried what he sees as the ‘expression of emotions and attitudes’ that have dogged discussions of SD, with ‘very little analysis of sustainable paths for a modern industrial s...