eBook - ePub

Professional Development in Higher Education

A Theoretical Framework for Action Research

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Professional Development in Higher Education

A Theoretical Framework for Action Research

About this book

This study offers a theoretical framework for professional development in higher education and examines the priorities for teachers' careers in the 1990s. It may be used as a companion volume to the author's work, "Action Research in Higher Education".

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Professional Development in Higher Education by Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Praxis in higher education

The companion book, Action Research in Higher Education (Zuber-Skerritt, 1992) presents case studies of developments in learning and teaching at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, together with reflections on these case studies. This part is a brief discussion of praxis in higher education. Praxis is defined as reflective practice informed by theory.

The first introductory chapter is a brief outline of Schwab’s (1969) distinction between technical and practical reasoning, with references to my case studies in the companion book on the one hand and to principles in the theoretical framework developed in this book on the other.

Chapter 2 is a discussion of the relationship between theory and practice perceived as dialectical rather than dichotomous. In other words, practice in higher education is not seen as non-theoretical, but as being informed by educational and personal theories; and educational theory is not considered to be non-practical, but rather as useful for the improvement of practice in higher education, if it is ‘grounded’ in practice. Both theory and practice are perceived as two sides of a coin handled by the active, ‘reflective practitioner’ as ‘the personal scientist’ and the ‘critical education scientist’ (explained in Part 2).

Part 1 therefore prepares the ground for Parts 2 and 3 (i.e. for those theories in higher education which integrate theory and practice, research and learning/teaching, reflection and concrete experience).

Chapter 1

Practical reasoning

Introduction

While it is common in any discipline to distinguish between two departments, that which deals with the principles or methods of the particular discipline (theory) and that which applies them (practice), this dichotomy in itself is problematic. Practice in higher education usually means the application of educational theory, but it may also be understood as the exercise of the teaching profession in higher education; the whole action or process of learning, teaching, and staff development; or the skills gained from this process and experience.

This book takes an integrated approach to theory and practice (i.e. to educational research and the practice of learning and teaching). It adopts a metatheoretical perspective on higher education concerning alternative modes of theorising, not only about the theory of higher education, but also about the practice and the relationship between theory and practice.

In this chapter I introduce Schwab’s (1969) notion of technical and practical reasoning and its relevance to higher education. I then discuss a specific case of ‘praxis’ in higher education in relation to some theories and principles of learning and knowing (referred to in brackets and italics) which will be explained in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Technical and practical reasoning

Schwab (1969, 98) in his well-known paper ‘The practical: a language for curriculum’ distinguishes between the theoretic and the practical in curriculum, drawing upon Aristotle’s distinction between technical and practical thinking or reasoning:

By the ‘practical’ I do not mean the curbstone practicality of the mediocre administrator and the man on the street, for whom the practical means the easily achieved, familiar goals which can be reached by familiar means. I refer, rather, to a complex discipline, relatively unfamiliar to the academic and differing radically from the disciplines of the theoretic. It is the discipline concerned with choice and action, in contrast with the theoretic, which is concerned with knowledge.

Schwab (1969, 98) argues that the field of curriculum:

(a) is moribund because of its inveterate and unquestioned reliance on theory which is either inappropriate or inadequate to the tasks of solving the problems it was designed to attack;

(b) is in a crisis which is evident in the flight of its practitioners from the subject of the field; and

(c) can only be regenerated… if the bulk of curriculum energies are diverted from the theoretic to the practical, to the quasi- practical and to the eclectic. By ‘eclectic’ I mean the arts by which unsystematic, uneasy, but usable focus on a body of problems is effected among diverse theories, each relevant to the problems in a different way.

Schwab’s advocacy of the practical in education is not totally new. As Kemmis and Fitzclarence (1986) point out, it is a call for a return to an old, venerable and still-living tradition of educational thought and action, in which the ‘arts of the practical’ (i.e. the arts of moral and political arguments) are more central to thinking about education than they are in the new ‘progressive’ natural science movement in education which arose towards the end of the last century and developed throughout this century.

Aristotle had already ranked practical above technical reasoning. Technical reason and action are guided by established theories, by following and applying rules, by employing means to attain given ends, and by evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness in those instrumental means-ends terms. In contrast, practical reason and action are essentially risky; they are guided by general and sometimes conflicting moral ideas about the good of humankind; and they involve wise judgement and moral decisions which to Aristotle were the main requirements for politicians and leaders of the state.

For higher education, this means that good teaching cannot be reduced to the technical application of educational theories, principles and rules, but that it involves not only constant practical judgement and decisions about alternative strategies to achieve given objectives, but also competitions and conflicts about which objectives and what kind of objectives should be pursued at any particular time. Practical reasoning requires the arts of wisdom and responsibility.

What are the requirements of the ‘practical arts’ and how can they be developed? Schwab (1969) describes four facets of the practical arts. The first begins with the requirement that existing institutions and practices must be altered piecemeal in small progressions, rather than being dismantled and replaced, so that the functioning of the whole remains coherent. This change, in turn, requires knowledge of the particular educational context, that is, empirical studies of educational action and reaction; new methods of empirical investigation, and a new class of educational researchers. A second facet of the practical is that it starts directly and deliberately from the diagnosis of problems and difficulties of the particular curriculum, not from aspirations imposed from outside the field. A third facet of the practical requires ‘the anticipatory generation of alternatives’ instead of waiting for the emergence of the problem itself. This means developing alternative solutions to identified curriculum problems. Finally, the practical requires a method of deliberation, a sensitive and sophisticated assessment of the behaviours, misbehaviours and non-behaviours of students.

To Schwab, a commitment to practical deliberation concretely means the establishment of new forums of communication for practical research in the field of curriculum (e.g. new journals, new forms of staff development and new kinds of research). Stenhouse (1975) takes Schwab’s notion a stage further by giving examples of how to establish this new research tradition. His ‘extended professionals’ are individual teachers-as-researchers who take responsibility for appropriating curriculum research and development and for testing their theories in their own teaching practice. Kemmis and Fitzclarence (1986, 51) extend this notion of the profession as a source of critique of practitioners’ own theory and practice by suggesting that the profession become an organised source of critique of institutionalised education and of the state’s role in education:

Moreover, critical curriculum theorising does not leave theorising to experts outside the schools, nor does it constrain curriculum theorising to the work of individual teachers and groups of teachers within schools; it offers forms of collaborative work by which teachers and other educationists across institutions can begin to form critical views of education which can challenge the educational assumptions and activities of the state, not only in theory (through having critical ideas) but also in practice (by establishing forms of organisations which aim to change education — a practical politics of education).

The notion of practitioners as researchers is discussed in more detail in the companion book, and exemplified by the case studies there. In particular, the case in Chapter 6 of Action Research in Higher Education (Zuber-Skerritt, 1992) is an example of practical deliberation and critical curriculum theorising — or in other words, an example of praxis in higher education.

The case of praxis in higher education

In the remainder of this chapter, an attempt is made to explain the above case in terms of the main theories presented in the subsequent chapters of this present book. The aim is to show the relevance of these theories to practical and emancipatory action research for change and development in higher education. To begin with, the following is a brief summary of the case under consideration for the benefit of those who have not read, or who need to be reminded of the content of, the companion book.

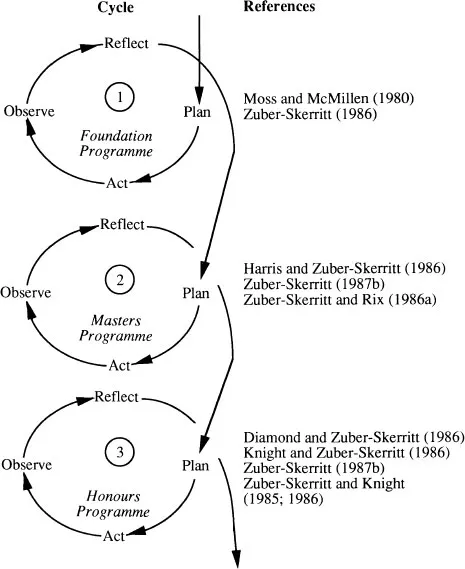

The case is me, a senior consultant in higher education working with teaching staff in the School of Modern Asian Studies (MAS) at Griffith University on action research projects on developing student learning and researching skills. The first cycle in the action research spiral consists of:

• planning strategies for helping undergraduate students become reflective, autonomous learners;

• acting (i.e. implementing the strategic plan);

• observing and evaluating the action using a variety of methods; and

• reflecting on the results of the evaluation individually and as a team, in discussions and publications, leading to the identification of new areas of concern and further action research.

The second cycle in this case consists of similar activities and processes for helping Master by Coursework students learn how to develop their dissertation research and writing skills; and the third cycle focuses on action research into developing Honours students’ research competencies, awareness of research paradigms and awareness of research effectiveness. Figure 2 (reprinted from the companion book) represents the three stages in the case with reference to publications arising from each cycle in the action research spiral.

Figure 2 The spiral of action research into developing student learning skills

The case can now be discussed in relation to the main theories included in this book, namely Kelly’s (1955; 1963) personal construct theory (Chapter 4), Leontiev’s (1977) theory of action (Chapter 5), critical education science (Chapter 6) and the CRASP model (also Chapter 6).

The case in relation to Kelly’s theory

Those people involved in the case were the convenors of the courses, the teaching teams, the students and myself as a teacher as well as an educational adviser. Each cycle has shown how each group of participants came to know and learn: students learnt to discover the processes of their learning and how they might influence them; staff learnt to discover the problems in their practice with students and how to alleviate them; I learnt to discern the processes by which students, staff and I might influence our own learning, understanding and any educational constraints.

All of us experienced Kelly’s theory in this case: that we need not merely accept and apply theories, rules and principles to our tasks (of studying, teaching, administration) in a technical manner, but that we are ‘personal scientists’ (capable of construing our own and others’ experiences, of hypothesising, testing our hypotheses, and of anticipating and predicting future events which again have to be tested and submitted to critical reflection and self-reflection). Kelly’s repertory grid technique designed to elicit personal constructs and theories is explained in Chapter 7 of this book and applied in the case studies of Chapters 4 and 5 in the companion book.

The case in relation to Leontiev’s theory

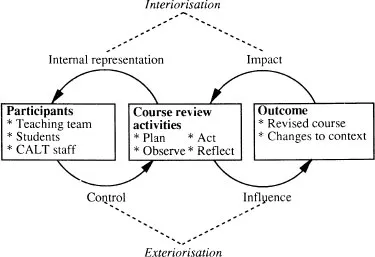

In Chapter 5 the implications of Leontiev’s theory for higher education in general will be discussed. With reference to this particular case, Leontiev’s subject-action-object model may be adapted as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The case of course reviews as action research (after Leontiev, 1977)

The ‘action’ in this case consists of the course review activities as action research (i.e. as the spiral of three cycles of planning, acting, observing and reflecting). The ‘subject’ in control of the action is the teaching staff themselves, in collaboration with the students in MAS and staff in the Centre for the Advancemen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part 1: Praxis in Higher Education

- Part 2: Theory in Higher Education

- Part 3: The Integration of Theory and Practice

- Part 4: Professional Development in Higher Education

- Conclusions

- References

- Author index

- Subject index