- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This major new text offers a clearly structured introduction to the economic and social development of Western Europe since the Second World War. A team of experts explore key aspects of postwar Europe's economy and society in a number of thematic chapters, with a regional and strongly comparative focus and these are followed by specific national studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Western Europe by Max Schulze in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Since the end of the Second World War, western Europe’s total output rose fivefold and per capita output increased more than three times. In 1946, European Gross Domestic Product per head was less than half that of the United States. By the mid-1970s, incomes in western Europe had reached about three-quarters the US levels and the gap continued to narrow thereafter, albeit at a slower rate. The growth of GDP per head may be a crude proxy for the rise in the ‘standard of living’, but there is no doubt that the increase in material prosperity was probably the major characteristic of economic and social development in western Europe since 1945.

This impression is confirmed, for instance, when we look at measures such as life expectancy and infant mortality. In 1950, the average male in western Europe had a life expectancy at birth of about 64 years; half a century later this had risen to 74 years. Similarly, females’ life expectancy at birth rose from 68 years in 1950 to 80 years by the mid-1990s. An even more dramatic change can be observed in infant mortality which fell by nearly 85 per cent between 1950 and 1994.

In contrast to the years before the war, increasing prosperity was, broadly speaking, common across western Europe – with important political implications. This book is concerned with the causes and consequences of the common European experience and is written primarily for the non-specialist reader. Each chapter provides an outline of historical development, some specific examples or case studies, and a summary of historical debate. A brief annotated bibliography at the end of each chapter offers a guide to further reading.

The structure of the book is designed to encourage readers to approach the main problems in post-war European economic development from both a thematic and a chronological perspective. There are three broad sections.

Part One traces the course of the European economy since 1945 and starts with an account of the impact of war on human and physical resources. This is followed by a discussion of post-war reconstruction and the beginnings of European economic integration. Of the next two chapters, the first explores the pattern and origins of rapid economic expansion during the Great Boom that stretched from the early 1950s to the early 1970s. The second examines the slow-down in economic growth, the problem of inflation and the rise in unemployment that occurred in the 20 years since. The extent, the causes and the economic consequences of structural change since 1945, including the issue of ‘deindustrialization’, are discussed in Chapter 6. This is followed by the analysis of the development of western Europe’s foreign trade and payments from the 1950s. The rise of the welfare state in post-war Europe and the debates about its long-term viability are examined in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 deals with the ‘institutionalization’ of economic integration in the European Community since 1958.

Part Two explores long-term forces of economic and social change. Chapter 10 analyses the causes and consequences of demographic change since 1945 and asks whether demographic behaviour in different countries converged over time to a European ‘norm’. The next chapter looks at the extent and changing nature of European immigration and examines its causes and economic consequences. Emphasizing the importance of distinct national traditions, Chapter 12 reflects on post-war educational reform in Europe as a response to perceived labour market requirements and increasing social aspirations. The next chapter offers an assessment of the social and economic consequences of technological and demand changes in transport and communications. Chapter 14, on the process of urbanization, analyses the relationship between structural change in the European economy and changes in the spatial distribution of production and consumption.

Adopting a country by country approach, Part Three considers the aims, priorities, conditions and outcomes of national economic policies in the Benelux countries, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia and Spain respectively.

Finally, the conclusion of this book seeks to place post-war economic change and integration in western Europe into a long-term historical perspective that takes account of development in the late nineteenth century and the inter-war period.

2 The Legacy of the Second World War

Economic Growth during the War

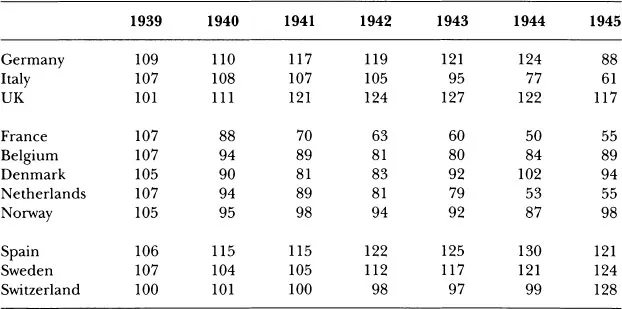

Wartime disruption both to geographical boundaries and to the price mechanism makes it difficult to give a precise account of the growth of the national economies during the Second World War, particularly in 1944 and 1945 when a lot of economic activity in continental Europe probably moved into the unrecorded informal sector. However, Angus Maddison has estimated a consistent set of real data covering our economies for this period and these are shown in Table 2.1.1 Not surprisingly, those economies which experienced land fighting ended the war with levels of real GDP below their pre-war level, whereas the war enhanced the levels of real GDP of those economies that avoided land fighting (the UK and the neutral economies).

Apart from the neutrals, the only economies which appear to have received overall sustained stimulation from the war were the UK and Germany. At their respective peaks they had a level of real GDP 27 per cent (in 1943) and 24 per cent (in 1944) higher than it had been in 1938. The decline in UK real GDP after 1943, reflecting the fact that munitions production had reached the level necessary to launch the liberation of Europe, was fairly steady, but in Germany the devastation that came with the land war which culminated in defeat brought a dramatic decline in real GDP of almost a third in 1945. By contrast the performance of the other major combatant, Italy, was consistently poor: real GDP peaked as early as 1940 (and even then it was only 8 per cent higher than in 1938) and it declined rapidly after the Allied invasion in 1943.

The occupied countries, France, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, all experienced a similar pattern of invasion and occupation leading to a decline in real GDP in 1940. Of these economies Denmark was the quickest to recover and indeed in 1944 its level of real GDP exceeded its 1938 level (although it subsequently fell back in 1945). Following its liberation in the summer of 1944 Belgium also started to revive but there was no recovery in the other occupied economies until the last year of the war. Occupation was most severe for France and the Netherlands: by 1944 both had seen real GDP reduced to about half its pre-war level and the gains made in 1945 were modest.

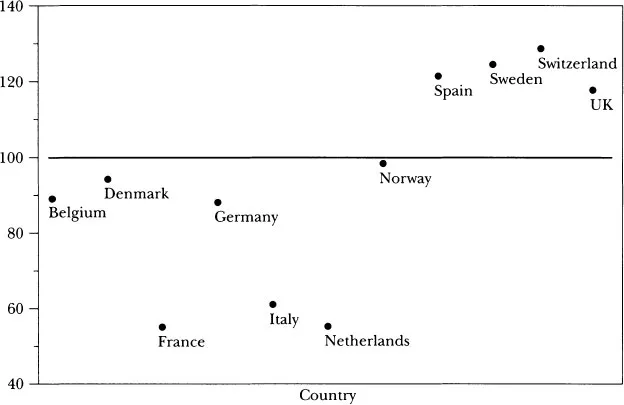

Figure 2.1. Real GDP in 1945 (1938= 100). Source: calculated from A. Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy 1820–1992 (Paris, 1995).

Table 2.1. Real Gross Domestic Product, 1939–45 (1938= 100)

Source: calculated from Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, pp. 162–3, 181, 183–4; Maddison derived his real GDP figures using a purchasing power parity method based on 1990 prices.

Furthermore, Table 2.1 overstates the actual living standards enjoyed by those in the occupied economies because it does not take into account their exploitation by Germany. The occupied economies were subject to occupation levies by Germany. France, in particular, suffered, transferring about a third of its output to Germany during the period of occupation and supplying more than 40 per cent of the total foreign occupation income received by Germany.

For Germany the foreign contribution amounted to about one-seventh of GDP and it helped to ensure that the reduction in German living standards was small.2 Germany also used its position to impose highly favourable exchange rates on other continental economies and to boost its imports of industrial and agricultural goods from the western occupied countries (for example, it has been estimated that during the occupation Belgium supplied between two-thirds and three-quarters of its manufacturing output directly to Germany); and as a last resort it could simply seize what it needed from them (indeed, many of the goods and services provided to Germany by the occupied countries were never paid for).

Of the neutral countries, the war proved beneficial for Spain and Sweden which were both important suppliers to the German economy; in particular, Swedish iron ore was a key strategic input for the German war economy. By 1945 Swedish real GDP was 24 per cent higher than it had been in 1938 and at its peak in 1944 Spain had seen a gain of 30 per cent. The geographical position of Switzerland made it more dependent on German goodwill and the curtailment of Swiss imports partly explains its sluggish wartime performance. However, 1945 brought a marked upturn in Swiss fortunes and real GDP increased sharply.

The Impact of the War on the Structure of GDP

Most of the economies involved in the war underwent a marked shift in the composition of their GDP as government expenditure expanded at the expense of consumption, investment and net exports. In the UK and Germany the expansion of the state sector mainly reflected the need to finance their massive war effort. In both countries the state came to dominate the economy, although in Germany the trend had begun before the war and its extent went much further: in 1939 about a third of German national income was already devoted to the war effort, with the UK devoting less than half that amount; by 1943 the German figure had risen to about 70 per cent (and it was probably even higher in 1944) and the UK had peaked at 55 per cent. In contrast, the weaker commitment of Mussolini to the war was reflected by the fact that at its peak, in 1941, the Italian economy devoted less than a quarter of GDP to the war effort.

In the occupied economies the expansion of the state sector reflected the enlarged bureaucracy needed to administer them and the high level of the occupation levies. Although during the war state expenditure also grew in the neutral economies, it did not come to dominate economic activity to the same extent; for example, in the case of Sweden government expenditure as a percentage of GDP increased from 9 per cent in 1938 to 14 per cent between 1941 and 1943.

In a peacetime economy consumption typically dominates GDP but the massive expansion of the government sector and the changes in output this entailed inevitably meant that consumption contracted severely, for example in the UK the share of consumption in GDP fell from 79 per cent in 1938 to 52 per cent in 1943. Germany had already experienced a marked decline in private consumption in the 1930s, from 71 per cent of national income in 1928 to 59 per cent in 1938, but this did not prevent real per capita consumption falling a further 30 per cent between 1938 and 1944 (compared to a 14.5 per cent decline in Britain between 1938 and 1943). However, until 1943 most of the increase in German government expenditure came not from squeezing domestic consumers but from squeezing the consumers in the occupied economies. This in turn added to the burden on the occupied economies: in France, for example, consumption was less than half of its pre-war level (Belgium and the Netherlands suffered similar, if slightly less severe, fates whilst Denmark was the least affected of the occupied economies).

Investment often contracts in wartime because the danger of damage by enemy action makes any new investment extremely risky, and war also acts to discourage and curtail trade (shipping blockades and the bombing or sabotage of key transportation links being an important form of economic warfare). Furthermore, both investment and trade came to be dominated by the war needs of the state. In both Germany and the UK civilian house building was squeezed in order to increase the allocation of investment resources to war production. The UK lost its continental market...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- PART ONE: THE EUROPEAN ECONOMY SINCE 1945

- PART TWO: LONG-TERM FORCES IN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGE

- PART THREE: NATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICIES

- Key Dates and Events

- Notes on Contributors

- Index