![]()

PART 1

Best Practices in the Deployment of Renewable Energy for Heating and Cooling in the Residential Sector

![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Background

In 2007, a report entitled Renewables for Heating and Cooling – Untapped Potential was jointly prepared by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Implementing Agreement on Renewable Energy Technology Deployment (IEA-RETD).1 This report provided an overview of renewable energy for heating and cooling (REHC) technologies and discussed the applications, market status and research needs and priorities for these technologies. The report also included a study of current programmes supporting REHC deployment in 12 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and a short discussion of good practices and lessons learned for each tech type of policy instrument.

The Renewables for Heating and Cooling – Untapped Potential report concluded that REHC technologies can offer net savings (based on life cycle cost) compared to conventional heating systems, but that the economic viability of these systems varies greatly by location. The study found that well-designed programmes for market development do exist and that there is potential for many countries to increase their current use of REHC technologies. The study concluded with several recommendations urging governments to develop programmes to increase REHC technology use. It also recommended ‘a review of best practices and lessons learned’ by leading countries in developing programmes to support REHC technologies and a sector-specific analysis to evaluate which approaches are most appropriate for each of the residential, industrial, commercial and institutional sectors.2

Building on, and following, the recommendations of the earlier work, this current project was commissioned under the IEA-RETD to examine the REHC technology status in a set of countries, identify and investigate significant residential-sector REHC support programmes in these countries and develop and analyse a set of best practices from these programmes.

This book summarizes the work performed during the above-described project. As part of the project, a stand-alone companion document, Renewable Heating and Cooling Best Practices Guide, was developed for programme developers at all levels. This latter document makes up Part 2 of this book.

1.2 Objectives

The overall objective of this project was to develop materials ‘to assist policymakers in developing robust, effective, sustainable programmes that can overcome the most common barriers that occur in deploying REHC in the residential sector’.3 More specific objectives were:

• To assess REHC programmes in the residential sector and identify those that have been the most effective.

• To profile the resulting best practices in portfolio planning and programme design, implementation and evaluation.

• To create a guide of practical steps and methods to implement the best practices.

• To effectively communicate and disseminate the best practices and guidance to appropriate audiences, including policymakers.

1.3 Project scope

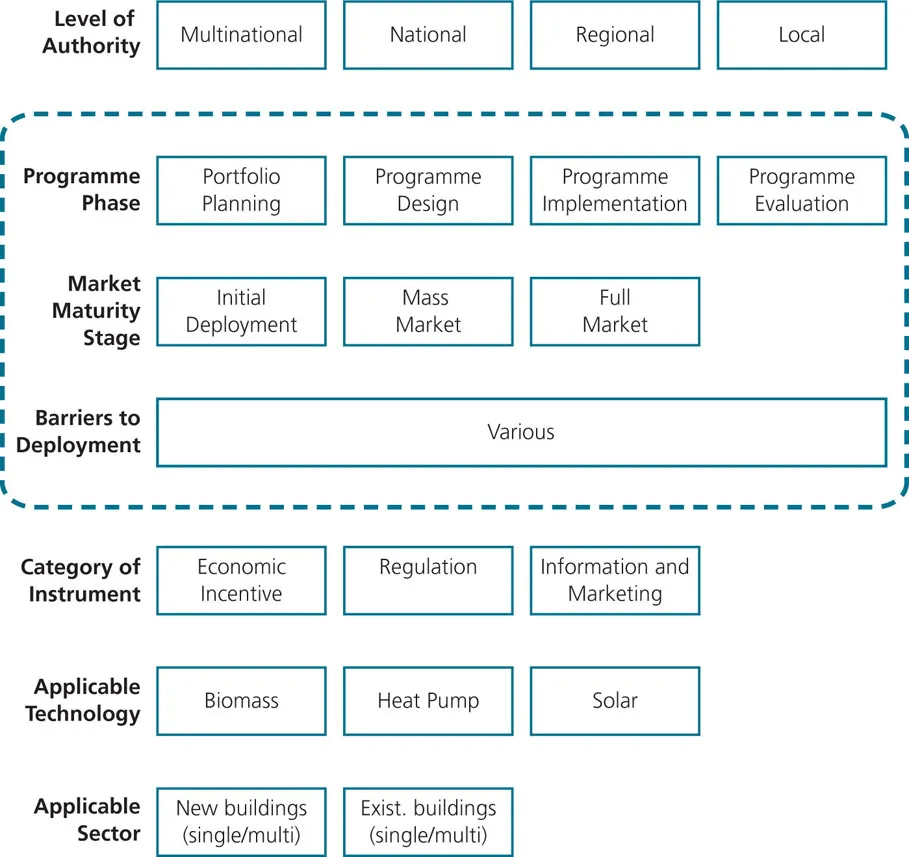

As illustrated in Exhibit 2, the scope of this project is defined in several dimensions: audience level of authority, programme phase, stage of market maturity, barrier to deployment, instrument category, target technology and applicable sector. The dimensions inside the dashed box: programme phase, market maturity stage and barriers to deployment, were used to organize the best practices in Part 2.

Exhibit 2 Project scope dimensions

1.3.1 Audience level of authority

The Best Practices Guide (Part 2) developed during this project is intended for personnel responsible for renewable energy portfolio planning and programme development, implementation and evaluation at all levels of authority: multinational, national, regional and local.

1.3.2 Programme phases

REHC programme design and implementation can be divided into four phases:

1 Portfolio planning encompasses initial problem definition and goal clarification, setting objectives, consideration of options and alternatives, identifying intervention points, identifying stakeholders and conducting consultations (if necessary), and selecting instruments.

2 Programme design can be done by the funding agency or a third party. Ideally, the programme design is based on the work done during the portfolio planning phase.

3 Programme implementation can also be done by the funding agency or a third party. During this phase, the programme is implemented.

4 Programme evaluation closes the loop by assessing progress against objectives, and reassessing both programme logic and processes. The programme is then modified as required. Evaluation is usually best done by individuals not involved in the programme design and implementation.

This project targeted all four programme phases.

1.3.3 Market maturity stages

Programmes designed to develop REHC markets can be categorized in the following manner:

• ‘Initial deployment’ programmes are appropriate for a market that is the initial stage. In this type of market, the public is largely unaware of the technology, the technology is not readily available and installation and maintenance support is difficult to find. REHC programmes for this market stage include demonstration and pilot projects. Training for retailers and installers is also appropriate.

• ‘Mass market’ programmes are aimed at a market that has passed through the initial deployment stage. The technology is becoming better known to the public, is being sold by retailers, and competent installers can be readily found. Appropriate REHC programmes include ‘carrot’ programmes, such as economic incentives, and ‘guidance’ programmes to educate both the public and industry members. In some specific situations, such as under certain political conditions, ‘stick’ measures may be appropriate, although these are more typically found under ‘full market’ conditions.

• ‘Full market’ programmes target well-developed markets. In these markets, the public is knowledgeable about the technology and its benefits, the technology can be easily obtained and an adequate number of well-trained installers are in place. ‘Carrot’ measures may still be appropriate, but ‘stick’ measures such as mandatory installation regulations may be appropriate for bringing non-participants into the market.

Note that it is not unusual for different REHC technologies to be in different market stages in a given geographical area.

This project targeted all three market maturity stages; however, most programmes examined were aimed at either ‘mass market’ or ‘full market’ stages.

1.3.4 Barriers to deployment

REHC technologies face a variety of barriers to wide-spread use. These barriers can be categorized in a number of ways. One method uses five ‘A’s:

1 Acceptability: Some REHC technologies may not (yet) be as easy to use as conventional technologies. Maintenance costs might be higher, reliability might not be as good or use may not be as convenient.

2 Accessibility: Laws, regulations or codes may make REHC installation or use difficult. For example, building codes may require expensive inspections of solar water collectors on roofs.

3 Affordability: Many REHC technologies are more expensive to install than conventional technologies. Financing for REHC technologies may be harder to acquire than for conventional technologies.

4 Availability: REHC technologies may have limited availability or lack qualified installers.

5 Awareness: The benefits of REHC technologies may not be well known, or potential users may not know how to obtain the technology.

Programme best practices vary not only by programme development phase and market stage, as described above, but also by barrier.

1.3.5 Instrument categories

Methods of involving public and industry in REHC programmes can be divided into three categories: economic incentives, regulations and information and marketing. Another common method of categorizing support instruments is with the descriptive terms ‘carrots’, ‘sticks’ and ‘guidance’. These categorization methods often, but not always, correspond to each other in a one-to-one manner.

• Economic incentives (often called ‘carrots’) include grants, loans, rebates and tax credits. Economic disincentives such as fines, on the other hand, would be ‘sticks’ (see below).

• Regulations (often called ‘sticks’) include building codes and laws requiring minimum installations. In some cases, regulations can be ‘carrots’ in that they make installing a REHC technology easier.

• Information and marketing (often called ‘guidance’) includes public awareness and education campaigns, quality assurance standards, support resources and training.

All three instrument categories were examined in this project.

1.3.6 Target technologies

The target technologies for this project are:

• Active solar thermal for air and water heating or cooling.

• Biomass (pellets, wood and wood waste).

• Geothermal (ground-source heat pumps).

• Heat pump technologies based on ambient air heat (air-to-air and air-to-liquid).

Active solar thermal systems

Active solar thermal systems can use either glazed or unglazed solar collectors.4 Unglazed collectors are employed in applications such as swimming pools and crop drying. Because this report is focused on the use of renewable thermal energy for space heating and domestic hot water, unglazed collectors have not been examined.

Glazed solar collectors can be divided into two major types: flat-plate collectors and evacuated tube collectors. Flat-plate collectors are appropriate for lower demand hot water systems, where the higher water temperatures produced by evacuated tube collectors could be dangerous. They are also often more appr...