![]()

Part I

Historical context and introductory concepts

![]()

Introduction to Part I.1:

historical context

Siân M. Griffiths

We start by using Hong Kong as a case study in historical development of public health and healthcare systems. Public health in Asia is introduced to us through the eyes of Professor S. H. Lee who was the Director of Health in Hong Kong between 1989 and 1994. An inveterate advocate of public health, Professor Lee is well known across the region – and indeed the world – not only as teacher and mentor of the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr Margaret Chan, but as a campaigner for health promotion and public health.*

As a former British colony, Hong Kong has much in common with other countries in Asia formerly under colonial rule, both benefiting from, and disadvantaged by, their colonial legacy. Whilst many structures are robust, the process of colonial handover back to China has also created inertia in the healthcare system as new forces come into play. For example, whilst primary care services in the UK have continued to develop and have taken up a greater role in public health service delivery within an integrated model, primary care in Hong Kong remains fragmented, mainly out of pocket and the population is prone to doctor shopping rather than being steered into secondary services through the gatekeeping role of the General Practitioner (GP). The majority of public health services continue to be provided by the Department of Health through the model of maternal and child health, school health and other clinic-based services, and population-based data necessary for assessing health outcomes are not routinely collected. As such, Hong Kong is similar to many other Asian countries in that its healthcare development has been influenced by history and its development closely tied to political and socio-economic changes. As a region, Asia has the highest number of countries that rely on out-of-pocket payment for health services and as such getting sick can be a catastrophic event not only for individuals but their families.

Taking a historical perspective, Professor Lee wrote from experience about the changes he has seen and some of the important formative events in public health. For example, he describes the impact of trade on patterns of infectious disease, in particular the epidemic of bubonic plague at the end of the nineteenth century, which stimulated the development of health services for all groups in the community, including the previously excluded Chinese locals. He describes the important scientific contribution made by Dr Yersin from the Institute of Pasteur in France and Dr Kitassato from Japan who together discovered the aetiology of plague whilst working in Hong Kong. Consequently, the importance of hygiene in the home and freedom from rats was underpinned by the public health policy of ‘Keeping the House Clean’. The need for good public health systems and control of infectious diseases was further underlined by the Temple Street outbreak of cholera in the 1960s, showing once again the need for good water through sanitation and illustrating the principles elucidated by John Snow and the Broad Street pump incident in nineteenth-century London. Further illustrations of the need for robust public health systems include the response to the influx of Vietnamese refugees who flooded into Hong Kong in boats in the 1970s, and by the SARS epidemic in 2003. SARS demonstrated the global nature of infectious disease, spreading from the index case in the Kowloon hotel not only into the local community but by air travel to Vietnam, Canada and mainland China within a few days. Professor Lee, as a member of the HKSAR Inquiry team, helped formulate the response to the epidemic, which focused on better communication, building resilience, enhancing research and increasing capacity with the founding of the Centre for Health Protection.

Hong Kong, with its rapid growth and need to build health systems to accommodate increasing urban populations, is an exemplar for what is occurring in many areas of global transition, facing rapid socio-economic changes and development with increasing wealth, but also facing the difficulty of providing equitable health services in social systems that leave the market to play a significant role in healthcare provision. Culturally determined choice of services is another important part of service provision and Professor Lee describes the importance of the role of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) – described later in the book in Chapter 41 – which is encouraged as part of the official policy not only in post-handover Hong Kong and in China, but across other Asian countries through the work of the WHO.

* Sadly, he passed away in January 2014, before he could see his chapter in print.

![]()

Historical perspectives in public health

Experiences from Hong Kong

S. H. Lee1

Introduction

History helps us understand the policies and problems we face today. This chapter will describe the history of public health in Hong Kong over two periods. The first period will cover the early days before World War II (1840s–1940s), and the second will examine public health after the end of World War II and be further divided into three phases, with each phase having its own distinct historical events. Phase 1 covers 1945 to 1960, Phase 2 covers the 1970s and the 1980s, and Phase 3 covers the 1990s to the present.

Early colonial medical service

Hong Kong was ceded to Britain under the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842. Lord Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary, described Hong Kong in 1841 as ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’. Sir Henry Pottinger, the first Governor of Hong Kong, reported in 1843 that ‘the island was visited by a great deal of severe and often fatal sickness. The major infectious diseases were dysentery, cholera and malaria, commonly known as “Hong Kong Fever”. Hong Kong Fever carried off 24% of garrison troops and 10% of European residents.’

The Hong Kong Government Gazette of May 1841 stated that the population consisted of some 7,450 fishermen and villagers. The newly arrived British traders were concentrated to build docks and warehouses on the waterfront. The construction work attracted many labourers from the Pearl River Delta.

Back then, tropical diseases were common among the British garrison force. In 1843, 24 per cent of the British garrison force and 10 per cent of the European residents had died of fever (malignant malaria), which gave Hong Kong an unwelcoming reputation for being the ‘White Man’s Grey Evil’.

In 1843, a government medical service was formed. In 1849, the Government Civil Hospital at Sai Ying Pun, which catered to police, civil officers and prisoners, was opened. The Chinese seldom used these services, partly because of their inability to speak English, but mainly because of their mistrust in Western medicine. With the support of Governor MacDonald, the first hospital for the Chinese, the Tung Wah Hospital, was built in 1870. In 1893, a missionary hospital, the Nethersole Hospital, was opened.

Early epidemics in Hong Kong prior to World War II

Bubonic plague

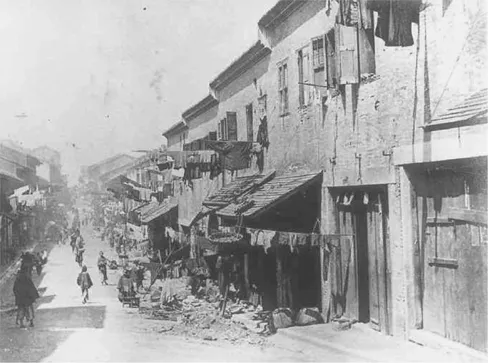

From 1894 to 1923, Hong Kong was severely affected by the bubonic plague. In the early days of the twentieth century, many working people from China came to Hong Kong to look for jobs. They usually concentrated in the western part of the island, in a district known as Tai Ping Shan Street (see Figure 1.1). The housing conditions, and the environmental hygiene and sanitation, in that district were very poor, which facilitated the easy spread of the disease.

Historically, there had been three pandemics of plague. The first two were commonly known as the plague of Justinian and the Black Death. The third was a major pandemic that began in China’s Yunnan Province in 1855. This pandemic spread to all inhabited continents and ultimately killed more than 12 million people in China and India alone.

In 1894, the bubonic plague also struck Hong Kong. The epidemic spread quickly among the overcrowded population of Tai Ping Shan. Hundreds of sick and dying patients filled the Tung Wah Hospital. After two months, the death rates dropped below epidemic rates, but the disease continued to remain endemic in Hong Kong until the late 1920s.

Figure 1.1 Tai Ping Shan Street in 1880 [1]

Following the spread of the plague, the Sanitary Board organized cleansing teams which consisted of medical officers, policemen, garrison members and volunteers to launch white washing and disinfecting processes in the infected areas. The year 1894 could be described as the ‘saddest and most disastrous year in history’, and a commemorative plaque was erected in a park near Tai Ping Shan Street to remind people of this epidemic.

The epidemic lasted for over twenty years, with 21,867 people being affected and 20,489 dying from the disease, a high mortality rate of 93.7 per cent. The practice of quarantine started in the early phases of the epidemic. Patients were isolated in a naval ship known as Hygeia. But the patients did not like being kept there and wanted to go to the Tung Wah Hospital instead. Although Hong Kong suffered severely from this epidemic, an important contribution was made with the discovery of the aetiology of the plague and development of effective measures against the epidemic. Dr Yersin from the Institute of Pasteur in France and Dr Kitassato from Japan came to Hong Kong and worked together to discover the aetiology of the plague. The importance of keeping the house clean and free from rats was fully realized, and the concept of ‘Keeping the House Clean’ began then.

Smallpox

Smallpox was also prevalent. A smallpox hospital was set up at Kennedy Town from the Tung Wah Infectious Disease Hospital. The disease remained a public health problem until the early twentieth century.2

Public health after World War II

Phase 1 (1945–1960)

This period saw the emergence of many infectious diseases and the expansion of public health services. The problems of refugees coming from China to Hong Kong covered two periods. The first period was in the late 1930s when many soldiers from the Nationalist army in China fled to Hong Kong during the Sino-Japanese War.

The second period was after World War II in the 1950s. In the immediate post-war period, many local residents who had fled Hong Kong because of the Japanese occupation had returned to Hong Kong. Overcrowding, poor environmental hygiene and sanitation, shortage of water supply and the spread of infectious diseases were the major public health problems at the time (see Figure 1.2).

The predominant infectious diseases were tuberculosis, cholera and common childhood infectious diseases, such as diphtheria, poliomyelitis, whooping cough and measles. The public health strategy adopted was to improve environmental hygiene, sanitation and water supply, and to develop maternal and child health services, which inclu...