- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Evaluation and Treatment of Eating Disorders

About this book

This important volume addresses a growing problem prevalent in hospitalized patients--eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Experts present the latest findings on the theories, evaluation, and treatment of this pernicious syndrome. Clearly written and up-to-the-minute, this outstanding collection of interdisciplinary vantage points, overlapping theories, and program applications will be of great value to front-line clinicians. Also included are historical perspectives, the treatment and rehabilitation of eating disorders, characteristics of families with eating disorders, and much more.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Occupational Therapy for Patients with Eating Disorders

Mary K. Bailey, OTR, FAOTA

ABSTRACT. The role of the occupational therapist and activity therapy programs for patients with eating disorders is described. Evaluation methods are outlined with specific comments related to their implications for patients with diagnoses of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Rationale for referral to specific activity therapy services is discussed. Group protocols are included. Two case studies demonstrate the utilization of occupational therapy and other activity therapies with an anorectic patient and a bulimic patient.

The Eating Disorder Program at The Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital consists of six beds housed within a 20-bed adult (ages 18-65), intermediate-care (30-90 days), inpatient hall. All patients including those with eating disorders are provided with activity therapy programming which may include: centralized hospital or hall-based groups and individual counseling to which they are referred for specific treatment objectives, leisure skill development groups which patients select themselves for one-month "courses," and open/optional activities in which patients use facilities (ex: gym, pool, hobbies room) with staff or volunteers who assist their experimentation with new media or provide opportunities to engage in familiar leisure activities.

Referred activity therapy groups are selected by a collaborative effort of the patient and the occupational therapist who functions as the representative or liaison between the hall and the activity therapy department. Selection is based on mutual acknowledgement of problems in areas of work, leisure, self-care, or identification and expression of feelings. Cognitive, motor, and social functioning in the aforementioned areas are evaluated in a variety of ways.

Evaluation Methods

Each patient receives and completes packet of forms. Leisure activities and values are surveyed on self-report forms based on Max Kaplan's theory of need satisfaction through activity participation (Kaplan, 1960; Herbert, 1969; Schwab, 1976). One form poses questions relating to self-perceived need of or value for engagement in leisure pursuits clustered within seven constructs: new and stimulating, familiar and quiet, altruistic, self-improving, externally organized or structured, creative, social. A companion form examines recent history of participation in activities reprsentative of the same seven constructs. Self-perceived strengths and weaknesses in social skills are reported on a self-attitude survey developed by the occupational therapy department at the Dwight David Eisenhower Medical Center at Fort Gordon, Georgia. The leisure and self-attitude surveys are scored numerically by systems developed by their authors. An additional questionnaire requires short narrative statements by the patient in answer to questions regarding stress management and independent living skills: cooking, use of community resources, apartment living, and money management.

All patients participate in a one-hour group session in which they arc asked to complete two tasks. One involves the use of paper, pencil, and ruler. Four verbal directions are given before the patients begin. This is a highly structured individual task. Evaluators score (on a scale of 1 to 5) such factors as memory, distractibility, dexterity, problem-solving ability, mental imagery, ability to parallel or generalize. The last two factors are elicited during a short discussion, and the patients are encouraged to consider their own reaction to the process.

The second task involves the creation of a group mural using pastels on a large sheet of brown paper. Evaluators score the following group interaction skills: participation, leadership, assertiveness, and negotiation and compromise in theme choice; participation, awareness of others, support of others, and social exchanges during the drawing.

In the short discussion following completion of the tasks, leaders assess the accuracy of the patients' perceptions of their own and others' roles in the activity. Again, patients are encouraged to examine the differences in their reactions to the individual structured, and the group unstructured experiences. They are advised to discuss preferences, strengths, and problem areas with their activity therapy representatives as treatment schedules are developed.

Patients attend a one-hour session in the gymnasium to evaluate gross motor function. For the first 30 minutes, they are invited to choose among a number of unstructured activities: paddle ball, shooting baskets, badminton, frisbee catch, etc. A team game is organized during the second 30 minutes. Evaluators assess patients' familiarity with sports, coordination, posture, reflexive reaction, flexibility, and pace. Group interaction and team skills are also assessed as well as the patients' approach or reaction to physical competition. Further screening is done for any obvious perceptual difficulties.

Evaluation of gross motor skills is delayed for newly admitted and severely cachetic, anorexia nevosa patients. Even when exercise is medically indicated, evaluators note and limit any tendency to overexercise in the quest for "burning" calories.

Each patient also participates in a group (four to five people) evaluation/orientation session co-led by a dance therapist and an art therapist. Movement and drawings are evaluated and discussed. The resulting written report forwarded to the occupational therapist also includes recommendations regarding referral to dance and/or art therapy.

The occupational therapist interviews each patient individually (Shaw, 1982). during the 45-60-minute interview, data is gathered regarding the patient's history and status immediately prior to admission in the areas of work or school, living situation, leisure and social pursuits and preferences. Problems, strengths, limitations, and resources are mutually identified using the results of the aforementioned procedures as well as data and opinions offered by the patient. The occupational therapist and the patient establish goals for treatment and discuss resources within the activity therapy program for addressing the identified problems, utilizing identified strengths and preferences and working toward agreed-upon goals.

Programming

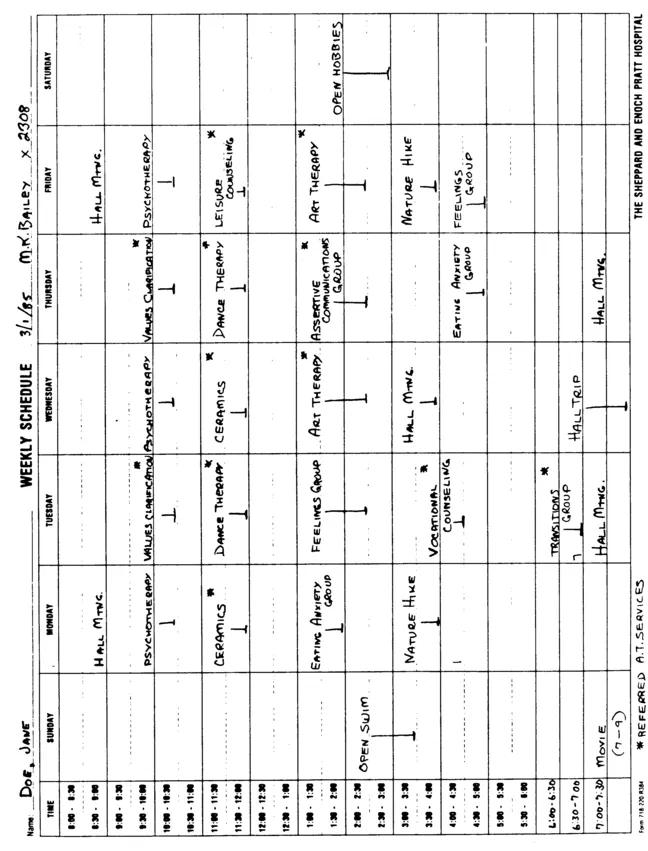

The occupational therapist is responsible for developing a schedule of activities for each patient. Referrals are written for groups, such as dance therapy, leisure education, cooking, ceramics; and/or for individual counseling, such as vocational counseling, leisure counseling, money management, apartment living. When the schedule of referred activity therapy sesions and individual or group psychotherapy is established, the new patient is counseled by the occupational therapist regarding selection of optional groups from the skill development and open activity schedules. Thus, the patient's first weekly schedule is established (Figure 1). Schedules are regularly reviewed, and progress reports are written twice monthly for the first 90 days and monthly therafter by group leaders and counselors who forward them to the referring occupational therapist. As the patients' needs change, new referrals are written, and schedules are modified accordingly.

Role of the Occupational Therapist

The assessment and programming responsibilities described above are part of the occupational therapist's role as activity therapy representative to the 20-bed hall. Additional components include documentation in the medical charts of all patients, participation in hall (patient and staff) meetings, hall staff meetings (clinical and administrative), patient evaluation and reevaluation conferences. Additional activity therapy staff with part-time resonsibilities to the hall include a dance therapist, an art therapist, a recreation therapist, and a vocational counselor. Coordination of their direct and indirect patient services is a part of the occupational therapist's role.

Additional clinical responsibilities include co-leading with a member of the nursing staff a New Comer's Group designed for orientation of all patients new to the hall. It is held twice weekly and touches on such subjects as hospital treatment philosophy, treatment team members, and hall procedures. Leaders facilitate patients' discussion of their fears and fantasies about hopitalization and how they experience the environment in the early days. Each patient attends a total of three sessions in the first and second weeks of hospitalization.

A group held twice weekly to acquaint the new patient with the activity therapy building and programs is co-led with a recreation therapist. This experiential group utilizes a variety of activities and facilities including: the greenhouse, the library, the hobbies room, the leather and ceramics area, the kitchen, and the game room. The group leaders involve other activity therapy staff as indicated in ses

FIGURE 1

sions which move from one area to another, some of which are held outdoors. At the end of each group hour, the activity is discussed by patients and staff in terms of its potential for therapeutic application. Each patient attends six to eight sessions.

The patients involved in the bating Disorder Program have a number of ongoing hall-based treatment activities included as a part of the established protocol (see article by David Roth, Ph.D, in this issue). Of these, the occupational therapist is involved in one, the Assertive Communications Group, co-led by the occupational therapist and a member of the hall's nursing staff. While patients in the eating disorder program are required to attend, the group members include other patients who reside on their hall.

Clinical Implications: Patients with Eating Disorders

Evaluation. The descriptions and dynamics of anorexia nervosa and bulimia patients are contained in other sections of this issue. In the activity therapy program, some significant patterns have emerged in evaluation procedures. Anorexia nervosa patients demonstrate little awareness of their own needs/values as measured in the leisure survey forms. Similarly, reported frequency in the related activities is far lower than is normal for women in their age group. By contrast, bulimic women often report investment in need identification as well as practice in one area of leisure activity with depressed scores for all others. It seems that they often pick one construct or area (for example, "sociability") in which to invest their energies to the exclusion of all others.

Almost without exception, women with eating disorders report dramatically lowered self-esteem with scores on the self-attitude survey lower even than those of other women with identified psychiatric disorders.

Anorectic and bulimic patients are clearly more comfortable with the very structured task described earlier as a part of the evaluation process. Their perfectionistic (Stober, 1980) tendencies lend themselves to tasks with predetermined end results, so their "perfection" is clearly recognizable. Their group interaction skills are uniformly diminished despite high level verbal and cognitive functioning, and they seem reluctant to involve themselves in a task in which they cannot control the outcome.

In the dance and art therapy assessments, body image distortions, painful self-consciousness, fear of expressive movement, sense of disconnected body parts, and immature images are among the usual reported findings (Bruch, 1982).

Programming in Activity Therapy

An Assertive Communications Group (Appendix A) (Alberti, 1974; Smith, 1975; Galassi, 1977) is included regularly in the schedule of the eating disorder patient. The basic concepts of the group address the self-esteem and control issues evident in women with eating disorders. Identification and appropriate expression of feelings in relationships are problematic for the anorectic woman who experiences only a narrow range of emotional reactions and who senses that, in any event, her feelings don't count (Bruch, 1982). As she begins to become aware of her emotions in psychotherapy, dance therapy, art therapy, and milieu groups, it is helpful to explore techniques for expression as well as to experience the curative factor of "universality" described by Yalom (1975). The anorectic woman discovers that others are sharing the pain of emerging awareness and the frustration of attempting to express feelings in a mature and effective way.

Of particular importance is anticipating and rehearsing (role playing) assertive ways to address changes in family relationships. Family therapy is a dynamic component of the total treatment program. The Assertive Communications Group provides patients with a supportive environment in which to examine and validate, review and rehearse their attempts at establishing independent and adult membership in the family ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Historical Perspectives and Diagnostic Considerations

- Behavioral Treatment of Eating Disorders

- Occupational Dysfunction and Eating Disorders: Theory and Approach to Treatment

- Occupational Therapy in the Rehabilitation of the Patient with Anorexia Nervosa

- Treatment of the Hospitalized Eating Disorder Patient

- Occupational Therapy for Patients with Eating Disorders

- Characteristics and Treatment of Families with Anorectic Offspring

- When Doing Is Not Enough: The Relationship Between Activity and Effectiveness in Anorexia Nervosa

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Evaluation and Treatment of Eating Disorders by Diane Gibson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.