- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on more than fifty interviews in both the US and the Netherlands, Wendy Chapkis captures the wide-ranging experiences of women performing erotic labor and offers a complex, multi-faceted depiction of sex work. Her expansive analytic perspective encompasses both a serious examination of international prostitution policy as well as hands-on accounts of contemporary commercial sexual practices. Scholarly, but never simply academic, this book is explicitly grounded in a concern for how competing political discourses work concretely in the world--to frame policy and define perceptions of AIDS, to mobilize women into opposing camps, to silence some agendas and to promote others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

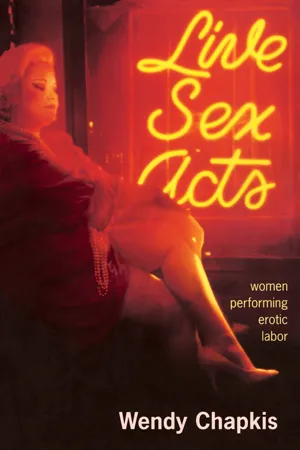

Yes, you can access Live Sex Acts by Wendy Chapkis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section III

Strategic Responses

Chapter 5

Prohibition and Informal Tolerance

Women’s experience performing erotic labor is highly determined by the conditions under which the work is performed. Under some circumstances, a worker’s control may be so radically diminished as to approximate slavery or indentured servitude. For abolitionist critics of prostitution, such cases serve as compelling evidence that the commercialization of sex is an inherently abusive transaction. From the perspective of prostitutes’ rights advocates, on the other hand, what makes prostitution abusive in some but not all instances is a question of the conditions under which the work takes place (the relations of production) rather than the terms under which the sex takes place (for money, love, or pleasure). These two very different perspectives have produced opposing strategic responses.

Those who view prostitution as an inherently abusive practice generally support prohibition of the act and punishment of some or all parties involved. In contrast, those who view prostitution as a form of labor tend to advocate policies designed to enhance worker control through decriminalization, regulation, and worker self-organizing. These competing perspectives have been advanced not only by those located comfortably outside the trade (such as academics, social activists, politicians, and policy advisors) but also increasingly by current and former prostitutes.1

The United States offers a useful example of the difficulties of achieving the abolition of prostitution through policies of prohibition. In the U.S., almost all forms of prostitution are currently illegal, but prostitution remains widely practiced throughout the country.2 Efforts to eradicate the sale of sex have proved to be as expensive as they are ineffective. In one recent study of American prostitution policies, legal scholar Julie Pearl uncovered the disturbing fact that in the 1980s, many of America’s largest cities spent more on enforcing prostitution laws than on education, public welfare, health care, and hospitals.3 The city of Los Angeles, for example, spent thirteen times as much on controlling prostitution as it did on health-related services.4 These expensive attempts to control commercial sex through prohibition have been also highly inefficient in curbing the practice: fully eighty percent of those arrested for prostitution in large U.S. cities are not held for prosecution, and only half of those brought to trial are found guilty.5 In other words, despite large investments of police time and resources in the entrapment and arrest of sex workers, very few are even temporarily removed from the streets.6

Police officials interviewed in Pearl’s study expressed serious doubt that “even a tripling of current law enforcement efforts could make a dent in the prostitution problems of their respective cities.”7 Nonetheless, they generally continued to support prohibitionist policies. Law enforcement’s enthusiasm for prohibition, then, appears relatively unrelated to its effectiveness in actually eliminating or even controlling prostitution. One California District Attorney suggests that while criminalization of prostitution may not work to abolish the practice, it plays an important role in creating a general climate of law and order:

When you talk about legalization, the overall problem is how you see the community and what kind of direction it will go in. Legalization is the first step in my mind to bringing other activities with it, where people will say, “Well, if prostitution is okay, then everything is relative.” You can then rationalize just about every kind of behavior even if it’s dangerous.8

In addition to any symbolic moral function it may play, prostitution prohibition also has a direct payoff for police. Prostitution arrests are relatively safe and easy to make and can improve the image of law enforcement in communities beset by crime. In the United States, in the 1980s, the majority (over seventy percent) of violent crimes committed in large cities did not result in arrest.9 This dismal crime-to-arrest ratio was improved, at least on paper, by cracking down on “victimless” crimes such as prostitution. During the same period in the same areas, arrests of prostitutes rose by one hundred and thirty-five percent.10 Energetic enforcement of prostitution laws thus served to create the impression of an active and efficient police presence even as it diverted scarce resources away from the control and prosecution of violent crime. As Pearl notes:

Prostitution cases raise the “closed by arrest rate” for total crime indices. Prostitution is one of the only offenses for which nearly one hundred percent of “reported incidences” result in arrest. To the extent that total arrest rate indices are elevated by the inclusion of this high percentage for prostitution, they engender a false account of overall police protection.11

An even more serious indictment of prohibitionist policies lies in their negative effect on the very population the laws ostensibly were created to protect: women understood to be “trapped” in the trade. Prohibitionist policies in the United States, as elsewhere, are the product of social purity and anti-trafficking campaigns, and were designed to prevent the exploitation of women in prostitution. However, efforts to protect workers by abolishing their places of employment or by arresting them (and their clients) have not served to enhance their general safety or well-being. Indeed, once prostitution has been criminalized, those charged with “protecting” prostitutes—the police—become a problem to be avoided instead of a resource upon which to draw. The resulting antagonistic relationship between prostitutes and police is a particularly serious problem in a profession in which participants face extremely high rates of violence.12 Fear of arrest also encourages hasty and euphemistic negotiations between prostitutes and clients which can undermine a worker’s authority and thereby her ability to protect herself. And, finally, laws against prostitution and “pandering” complicate workers’ efforts to share crucial information about safer working methods and dangerous customers. One member of the Prostitution Task Force of the California National Organization for Women argues:

Fear of the pandering law works to the detriment of prostitutes, as it discourages them from sharing information openly which may help them work more safely, to tell others of a safer, more pleasant place to work, or to educate each other or the public about their work in a manner which differs from its usual negative connotation.13

For these reasons, the California chapter of NOW passed a resolution in 1994 supporting decriminalization of the sex trade. The organization concluded: “Laws prohibiting prostitution are a prime factor in perpetuating violence against prostitutes.”14

This recognition that prohibitionist policies can threaten the safety and well-being of prostitutes has led some abolitionist activists to emphasize strategies targeting clients and third parties (business owners, landlords, and pimps) rather than workers. Cecilie Hoigard and Liv Finstad, for example, argue that because prostitution is a form of sexual violence, criminalizing the clients must be a priority:

Prostitution is like a piecemeal rape of women. Therefore, it is our view that prostitution should be defined as a crime of violence…. The demand can be … restricted by criminalizing those who represent the demand-side of the purchase.15

Over the past decade, this strategy has become increasingly popular in abolitionist countries such as the United States.16 In the 1980s, many U.S. cities passed laws allowing for the seizure of cars used in prostitution offenses.17 The intent was not simply to shift the burden of punishment from worker to client, but also to discourage prostitution through the public humiliation of those paying for sexual services. In Portland, Oregon, for example, motorists whose cars had been seized were not only obliged to pay fines of about $300, but were also required to have all parties on the vehicle registration— including wives or employers—sign off before a car could be released. The intent of this provision was made clear by one Portland police officer: “If you choose to use your car in this type of activity, you’re going to have a lot of explaining to do at home.”18 Over four hundred cars were seized in that city in a single year.19 In Washington, D.C., where similar laws are in force, a city council spokesperson complained that the law was so effective that the police “say they don’t have enough space to store the cars.”20 Of the 124 cars which were seized in that city in 1992, about half were simply forfeited, suggesting how serious the problem of stigmatization is for many clients.

Humiliation is also the explicit objective in many neighborhood vigilante efforts at curbing prostitution. One member of a San Francisco neighborhood group opposed to prostitution proudly reported, “I have personally called employers if there’s a logo on a company car or truck circling the block in search of women…. In two cases I know of, the men have been fired.”21 Through such efforts, punishment precedes not only (eventual) conviction but even arrest. Working prostitutes typically oppose these strategies. As a delegate to the First World Whores Conference argued:

First of all, arresting johns is bad for business. Secondly, it pushes us further underground where we’re more vulnerable. And thirdly, it misses the point: we want as much right to sell sex as men have to buy it; we don’t want punishment for them—we want rights for us.22

While prostitutes and johns are the primary targets of prohibitionist policies, other parties involved in commercial sex, such as landlords and business owners, also have been the object of public harassment and legal action. In the past few years, U.S. law enforcement officials increasingly have been employing so-called “Red Light Abatement” procedures (involving the seizure of property rather than the arrest of participants) to close commercial sex establishments. Police have found that the simple threat of loss of property often inspires landlords to take swift action in evicting tenants suspected of running brothels or engaging in other forms of illegal sexual commerce. Whether the procedure is effective in curtailing prostitution, however, is less clear. Shortly after the strategy was employed in one California city, the local paper reported:

Workers are neither leaving Santa Cruz, nor leaving the sex business because of the crackdown. They’re just going into less conspicuous, independent work. “They’re not rooting us out,” elaborated one woman, “they’re driving us underground, where it’s more dangerous.”23

As the U.S. example suggests, policies of prohibition appear to be ineffective as well as costly, and compromise the safety of those working in the trade. As a result, other countries increasingly are moving in the direction of legalization or decriminalization of the sex trade. No country has so fully embraced informal alternatives to prohibition as the Netherlands. While prostitution itself is legal in that country, third-party sexual commerce (such as brothel prostitution) is formally prohibited but informally tolerated.24 This “tolerance policy” (gedoog beleid) has resulted from coalition governments composed of Socialist, Christian Democratic, and Liberal (fiscally conservative) parties with radically differing views on “social problems” such as drugs and prostitution. Socialists and Liberals increasingly have embraced policies of formal decriminalization and regulation, while the Christian Democrats have held firm to an abolitionist morality without insisting on prohibitionist policies. The resulting strategy of tolerance has allowed the state to formally condemn prostitution and drug use while investing few resources in their prohibition and has ensured the survival of coalition governments across ideological differences.

The de Graaf Foundation, a Dutch research and documentation center on prostitution, notes that such tolerance policies have been relatively successful in controlling the Dutch sex trade, but they also have required authorities to make “creative use of roundabout methods or else operate in outright opposition to the legal code…. As long as no one went to the courts to stop it, a great deal could fall under the concept of ‘tolerance.’”25 Zoning policies, for instance, have been used to informally concentrate sexual commerce. Disgruntled residents of impacted areas have been offered state subsidies to relocate should they so desire.

But, as the de Graaf Foundation suggests, informal decriminalization requires not only the cooperation of authorities, neighbors, and businesses, it also depends on a willingness of all parties to turn a blind eye to the formal legal prohibitions on organized prostitution. In one Dutch city, Rotterdam, wh...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Section I: Sex Wars

- Section II: Working It

- Section III: Strategic Responses

- Afterword: Researcher Goes Bad and Pays for It

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index