eBook - ePub

People and Environment

Behavioural Approaches in Human Geography

- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1994. This book comprises a second edition of Human Geography, behavioural approaches, first published in 1984. The first edition attempted to synthesize the massive volume of geographical literature to have appeared mainly since 1960 concerned with both how people come to know the environment in which they live and with the way in which such knowledge influences subsequent 'spatial behaviour'. As with the first edition, the rationale for, advantages of, and shortcomings with behavioural approaches are explored at length in both substantive chapters and in a number of detailed examinations of particular aspects of life in advanced Western society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access People and Environment by D.J. Walmsley,G.J. Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Human GeographyPart 1 Introduction

Behavioural research in human geography really began in the 1960s. Its origins can be found in the dissatisfaction that was widely felt with the normative and mechanistic models of people–environment interaction that had existed before that time, based on such unreal notions as that of rational economic behaviour.

Basically behavioural approaches are non-normative and focus on the information-processing and acted-out behaviour of decision-making units (e.g. individual people, households, firms), special attention being paid to the constrained circumstances in which decisions are made. Behavioural approaches therefore focus on the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of behaviour and on the way in which individuals interpret and assign meaning to the environment. The scale and nature of such studies vary enormously. Early work tended to concentrate on overt behaviour (e.g. travel patterns) and on environmental perception (e.g. mental maps) but in recent years the scope of behavioural research in geography has widened considerably to take in the ‘scientific’ analysis of attitudes, decision-making, learning, and personality, as well as ‘humanistic’ examinations of the meaning that attaches to place and to landscape. Not surprisingly, there are parallels to be seen between what is happening in human geography and what is happening in other disciplines. Psychology, for example, has an increasing number of practitioners who argue that the discipline (1) should break away from its preoccupation with the behaviourist tradition (which essentially seeks to reduce complex behaviour to simple bonds between stimuli and responses); (2) should reduce its emphasis on artificial laboratory experiments; and (3) should look instead at behaviour as it occurs in natural situations. This viewpoint in clearly seen in ecological psychology and, in particular, in environmental psychology, and the links between these branches of the discipline and behavioural research in human geography are quite close.

One of the consequences of close links with psychology has been the adoption by geographers of psychological terminology. Very often this borrowing process has proceeded in a cavalier fashion. The term ‘perception’, for instance, is widely used and abused in the geographical literature. In many cases it describes a process that would be better labelled ‘cognition’. Loose terminology, and a fascination for what goes on in the mind at the expense of acted-out or observable behaviour, has brought behavioural researchers in human geography a great deal of criticism. It has been pointed out, for example, that the links between attitudes and perceptions on the one hand and ‘spatial behaviour’ (choices as to where people will live, shop, work, play, etc.) on the other are neither clear nor direct. More fundamentally, behavioural studies in geography have been charged with viewing the environment as given, and hence with overlooking people’s capacity to change the world. All too often, it is claimed, the focus of behavioural approaches has been on a value system that supports the status quo. In other words, behavioural approaches are often seen as being primarily concerned with the interpretation of behaviour as it is, with a result that little emphasis is given to the question of how behaviour might be changed so as to improve human well-being.

Despite these criticisms, behavioural research in geography has many practitioners. The distinction between objective and behavioural environments, that was postulated by early researchers, is a persistent and helpful one, as is the distinction between images and schemata. What seems to be needed in geography therefore is a greater attention to the philosophical and epistemological foundations of behavioural research so that a framework or paradigm can be devised that will bring together the varied efforts of all those researchers interested in people–environment interaction. Also needed is an explicit appreciation that much people–environment interaction is highly constrained, the important constraints in many cases being socially constructed (e.g. gender roles forced on people by social mores and by the mode of functioning of society as a whole).

Part One looks at the origins and growth of behavioural approaches to the study of people–environment interaction, particularly in relation to trends in other disciplines. It also outlines some of the objections that have been raised to behavioural research, and the reply that has been made to those objections. It is pointed out that the issue of how to relate form, structure, or pattern to behavioural process is one of the enduring problems in geography. Several philosophical approaches have been suggested as providing the key to overcoming this problem. Thus positivists argue that investigation of human behaviour by means of scientific method provides insights into the linkages between geographical form and behavioural process. Humanists, in contrast, are critical of scientific method because it concentrates only on what is measurable and therefore overlooks important issues like values and beliefs. Structuralists generally have no time for either positivists or humanists, preferring instead to view patterns of social life (e.g. human use of the environment) as resulting from the mechanisms (or ‘structures’) which underpin those patterns but which are not directly observable (e.g. structures in the brain, Marxist interpretations of the structure and functioning of political economies). The debate in geography between the positivists, humanists, and structuralists has at times been fairly vitriolic. Perhaps such differences of opinion belong to the past. Certainly, as Part One points out, there is evidence of a coming together of proponents of the various philosophical approaches. Both advocates of scientific method and humanists increasingly appreciate the importance of structures, whereas structuralists are coming to see that actual behaviour patterns may be one of the things that cause social life to take different forms in different places. The net effect of this discourse between the different positions is a revitalization of interest in behavioural approaches to the study of people–environment interaction.

1 People and Environment

Human geography has changed markedly since 1945 (Johnston 1979). The areal differentiation school of thought, which emphasized the delimitation of regions and the study of the characteristics that made them distinct, waned in popularity after having been the dominant geographical paradigm for much of this century. In its place came the quantitative revolution and the search for laws and theories. The application to geography of principles from both scientific method and the philosophy of science appeared to promise much (Harvey 1969a). A focus on the interrelationship between form and process, and in particular on the way in which behavioural processes brought about spatial patterns, encouraged geographers to turn their attention to model building. In human geography such models were probably best developed in what has become recognized as the locational or spatial analysis school of thought which sought to examine phenomena such as settlement patterns and the location of economic activity in terms of geometrical patterns and mathematical distributions (Haggett 1965). In many cases such model building derived its inspiration from micro-economics and was normative in approach in that it stipulated the spatial (i.e. geographical) patterns that should obtain given a number of assumptions about the processes that were supposedly operating. Commonly, the centre of attention was a set of omniscient, fully rational actors operating in a freely competitive manner on an isotropic plane. Indeed much of location theory was built around such ideas. Model building was seen by many as a way of making geography more ‘scientific’ and this was generally thought to be a good thing.

There have always been critics of normative model building in human geography and of attempts to develop the discipline along the lines followed by the natural sciences. Initially such criticisms came from two quarters: (1) an old guard of ‘regional geographers’ who defended areal differentiation as the core geographical method; and (2) those who believed that the goal of value-free, ‘scientific’ human geography was both undesirable and unrealistic (N. Smith 1979). Increasingly, however, criticism emerged from within the ranks of the practitioners of modern quantitative human geography. Disquiet focused on the fact that many normative models are grossly unrealistic in that they ignore the complexity of real-world situations and instead concentrate on idealized postulates such as rational economic behaviour. At the same time many models are overly deterministic in that there is only one logical behavioural outcome in any given situation. They are also reductionist in that they reduce everything to a question of economic returns and thereby overlook the fact that individuals have different attributes and motivations and respond in varying and very often non-economic ways to different environmental characteristics (Porteous 1977). Above all, the development of sometimes elegant models of spatial form and process, based around the notion of rational economic behaviour, has had little relevance for human geographers increasingly committed to using their skills in the solution of pressing societal problems.

It is not surprising, therefore, that dissatisfaction with the progress of the quantitative revolution in human geography, and qualms about the acceptability of normative models, have led to a number of developments within the discipline. For example, some researchers have turned away from the philosophy of science and sought guidance in moral philosophy. As a result, they have addressed themselves to questions of justice and equity in an attempt to appear ‘relevant’ (Harvey 1973). Others have abandoned the search for postulates of individual behaviour as a basis for understanding spatial form and have preferred to develop aggregate-level, descriptive approaches (exemplified by spatial interaction models) which conceptualize individual choice as a random process subject to certain overall constraints (Wilson 1971). Yet another approach, and one which is the focus of a good deal of attention in this book, has taken the view that a deeper understanding of people–environment interaction can be achieved by looking at the various psychological processes through which individuals come to know the environment in which they live, and by examining the ways in which these processes influence the nature of resultant behaviour. This does not, of course, mean that observed behaviour should be seen as the mere outworking of deep psychological processes. Such a view would be simplistic and wrong, given that the way in which people interact with the environment is often very highly constrained for one reason or another.

A behavioural emphasis in human geography is not of course entirely new: after all, the ‘landscape school’ in North American geography focused on humans as morphological agents and therefore tried to show how behavioural processes influenced landscape patterns. Similarly, advocates of human geography as a type of human ecology – a view that was very popular earlier this century – owed much to the possibilist philosophical position that stressed the significance of choice in human behaviour (Haggett 1965: 11–12). What distinguishes modern behavioural research in human geography from this earlier work is the primacy afforded to individual decision-making units, the importance given to both acted-out (or overt) behaviour and to the activities that go on within the mind (covert behaviour), a non-normative stance that emphasizes the world as it is rather than as it should be under certain theoretical assumptions, a concern to understand how socially generated constraints influence virtually all forms of people–environment interaction, and a willingness to consider those distinctly human characteristics that lead individuals to develop a sense of attachment to some places and a feeling of dislike for others. Not surprisingly, this new orientation has posed philosophical and methodological questions that have never before been tackled seriously by human geographers. Yet it would be wrong to view behavioural approaches to the study of people–environment interaction as a completely distinct branch of the discipline (possibly called ‘behavioural geography’, as advocated by some early researchers) because work in this field has tended to complement rather than supplant existing systematic branches of geography (e.g. urban geography, industrial geography). In other words, the subjects on which behavioural research has focused are often the same as those studied by both location theorists and relevance-orientated social geographers (e.g. the provision of urban services, travel patterns, migration). Even model building remains an important strategy with behavioural researchers, albeit with a positive rather than a normative research goal (i.e. a desire to understand the world as it is rather than as it should be under certain theoretical conditions). In order to appreciate the nature of behavioural approaches to the study of people–environment interaction, it is important to outline the character and significance of this work within human geography.

A behavioural paradigm?

To Gold (1980: 3), ‘behavioural geography’ (a term commonly used as a shorthand expression to signify the entire range of behavioural approaches used in the study of people–environment interaction) is a geographical expression of behaviouralism, which is itself a movement within social science that aims to replace the simple, mechanistic conceptions that previously characterized people–environment theory (e.g. the notion of rational economic behaviour) with new versions that explicitly recognize the enormous complexity of behaviour. To many, then, behavioural approaches in human geography constitute a point of view rather than a rigorous paradigm: the underlying rationale for the adoption of such approaches lies in the argument that an understanding of the geographical distribution of humanly made phenomena on the earth’s surface rests upon knowledge of the decisions and behaviours which influence the arrangement of the phenomena rather than on knowledge just of the positional relations of the phenomena themselves. In other words, morphological laws that describe geometrical patterns are insufficient for understanding how those patterns come into being. Process can only be uncovered if attention is directed to the decision-making activities of the actors involved in creating a given pattern (Johnston 1979: 117). This inevitably involves consideration of the way in which behavioural intentions can be frustrated by constraints of one sort or another.

Early reviews of behavioural approaches in human geography pointed out that two types of study were dominant: analyses of overt behaviour patterns (often travel patterns) and investigations of perception of the environment (Gould 1969). The former tended to be based on an inductive approach that sought to observe reality as a prelude to arriving at generalizations which described the behaviour under study. In this way, the emphasis was on discovering the general in the particular. This inductive approach therefore differed from normative model building which usually began from the opposite perspective with simplified assumptions about the motivations underlying behaviour. These were then used as axioms from which deductions could be made (as, for instance, when the practice of distance minimization is deduced from the postulate of rational economic behaviour). The same inductive element was evident in perception studies. The aim was to study particular instances of environmental perception so as to identify general principles, the assumption being that comprehension of the way in which an individual perceives the environment would help in understanding that individual’s behaviour. The rationale for this was set out clearly by Brookfield (1969: 53): ‘decision-makers operating in an environment base their decisions on the environment as they perceive it, not as it is. The action resulting from their decision, on the other hand, is played out in a real environment’.

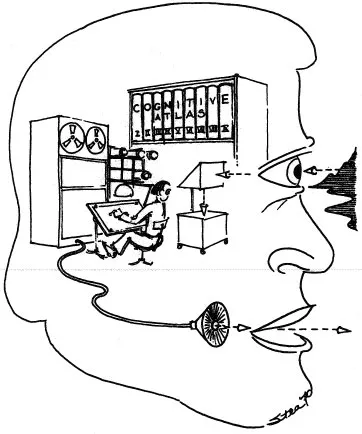

In these early behavioural approaches, no a priori assumptions were made about the perception process. Indeed, the interface between the environment and behaviour was thought of very much as a ‘black box’ through which humans formed an image of their world (Fig. 1.1). Burnett (1976) has attempted to identify some of the beliefs about the mind as a mediator between the environment and overt behaviour that are common in such black box situations and has examined the implications of these beliefs for an understanding of people–environment interaction (Table 1.1). In principle, this focus on the mind should have encouraged geographers to explore the whole issue of human consciousness. However, according to Guelke (1989: 290), by focusing on the environment as perceived in a rather simplistic sense, ‘geographers retained an essentially positivistic view of human geography’. In short, many researchers stuck with the tried and tested scientific method and focused only on what was measurable. They were therefore slow to realize the potential of those alternative approaches (often called ‘humanistic’) that emphasized human consciousness, values, subjectivity and intentionality.

1.1 A primitive view of environmental perception (Source: Stea and Downs 1970: 5)

Table 1.1 Beliefs inherent in the view that the mind is a mediator between environment and behaviour

Belief | Elaboration |

Minds exist and constitute valued objects of scientific inquiry | We are more concerned with the description of preferences and perceptions than the description of conditions of neurons and nerve fibres |

Minds are described in psychological and not neurophysiological language | Minds do not have peculiarly mental, non-material, or ghostly properties which would place them outside the realm of acceptable scientific discourse |

There is an external world of spatial stimuli with objective places outside the mind | These include things such as industrial agglomerations, central places, residential sites, etc. |

Minds observe, select, and structure information about the real world | Minds have processes corresponding to spatial learning and remembering and have streets somewhat corresponding to mental maps, perceived distances, awareness spaces, environmental cues, multidim... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part 2 Approaches to the Study of People and Environment

- Part 3 Fields of Study

- References

- Index