1.1 What is economics?

Economics only became an independent discipline around the year 1900. That was precisely when classical economics turned into neoclassical economics. Economists of those days tried to shape the new discipline along the lines of the natural sciences with the help of mathematics. They used the language of laws, mechanics, and equilibrium, as in physics, and they employed metaphors from biology, such as evolution and circulation of blood in the body. Image 1.1 shows a physics model of the economy, in which water flows represent the flow of resources and goods. Such a model was called a MONIAC (Monetary National Income Analogue Computer), and the one in the photos was a gift from the municipality of Rotterdam to Erasmus University Rotterdam in 1954.

1.1.1 Definition

There are many ordinary definitions of economics. Economics is said to be all about money. Or it is taken for granted that it studies markets and not other allocation domains as well. Or people assume that it analyses businesses and how they can maximise their profits. Others recognise a broader role for economics as studying the provisioning of the oikos, the classical Greek word for household: the oikos as the household of the state and communities.

Economists have often been characterised in not very flattering ways. A famous characterisation parallels the definition of a cynic by the 19th century Irish poet and novelist Oscar Wilde. This portrays economists as people who know the price of everything but the value of nothing . . . . This characterisation has a grain of truth, which is precisely why the Nobel Prize for economics was awarded much later than the original Nobel Prizes. And not from the legacy of Alfred Nobel, but initiated and financed by the Central Bank of Sweden as ‘The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel’, much to the dismay of the Nobel family who have distanced themselves from this additional ‘Nobel Prize’. It took some time before economics was recognised as a real science, and it is still disputed by some as window dressing for supporting business interests over societal interests.

Most economists, including myself, make a distinction between neoclassical economics, followed by about 90 per cent of economists, and heterodox economics, a variety of other approaches, followed by the remaining 10 per cent. I was trained as a neoclassical economist and was given a very brief and incomplete overview of heterodoxy by two lecturers. These short insights stimulated me to study heterodox schools of thought by myself. Later, I sent a clumsy paper I had written as an activist researcher in my first job to Amartya Sen, whose work I greatly admired. To my surprise, I received a friendly and encouraging short letter back. I did my PhD on the ethics hidden in economics. Now, I hold a professorship in Pluralist Development Economics at the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam and teach students from all over the world about pluralist economics. This is what this book is about: a pluralist introduction to economics.

Image 1.1 MONIAC at Erasmus University Rotterdam

Despite the mathematisation that began in the 1950s, economics is part of the social sciences. It studies human behaviour in production, consumption, entrepreneurship, labour, investment, and distribution. This behaviour is not only located in markets but also occurs through economic agents’ interactions with the state (in particular through paying taxes and receiving public services) and in communities – the community economy. So, economics is part of the social sciences and uses a plurality of theories and methods, both quantitative and qualitative, to explain a variety of economic behaviours in markets, the state, and communities. And for those who insist on a definition, here is one: economics is the study of how human beings interact for the provisioning of their livelihoods in markets, the state, and communities.

1.1.2 Purpose

What is the purpose of studying economics? The answer was formulated half a century ago by Joan Robinson, a well-known British economist working from the 1940s to the 1970s:

The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.1

Is economics a means–ends study, analysing how people use certain means to achieve particular ends? Well, to some extent yes, because the means are not endless. Most of the means to provide for oneself and ones’ dependents (children, the elderly) tend to be scarce. Not absolutely, but relatively. One would easily trade a scarce good like a diamond ring when lost in the desert and craving for water, while other goods seem abundant, such as clean air. But we make these goods scarce through pollution and waste. Scarcity is not an absolute but a relative limitedness of resources, influenced by economic agents. It is not an independent given, outside the agency of people. And therefore, economics goes beyond a means–ends study. That is because nothing is fixed. Scarcity, ends, and means are not fixed over time and space.

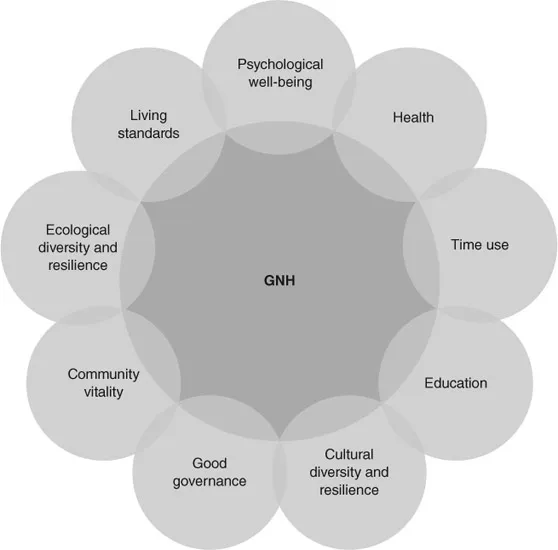

Innovation creates new means every day, from new ways of communication (remember how slow your first computer was and imagine how many additional features your cell phone will have in 5 years’ time) to innovative forms of food production (for example, algae fields in the sea, a rich source of proteins), to new forms of power (the successful lobbying by industry for a newly created virtual market in pollution permits rather than regulation). Also the ends are not fixed. Nobody cared to save money for a smart phone before the new millennium. And who is not influenced by advertisements in her choice of coffee, jeans, or movies? While at the same time, some people choose to live less materialistic lives, valuing social time or a spiritual life over more consumer goods. Sometimes, a whole nation decides on such a shift, for example Bhutan, which has moved its system of National Accounts towards a broader system of National Happiness (see Diagram 1.1).

1.1.3 Values

There is one more concept key to the description of economics: efficiency. Efficiency is an ethical value, like equality and fairness. If you have to clean your house, you generally prefer to get it done as quickly as possible with the least effort, that is, efficiently. Narrow efficiency concerns the maximisation of output with the minimisation of input. But what is efficient at one level – cleaning your house in the shortest possible time and with minimal effort – may be inefficient at another level – using electricity for a vacuum cleaner leading to CO2 emissions, and using chemical detergents, contributing to water pollution. So, efficiency can ideally only be assessed at the economy-wide level and even beyond, to include society and nature. This enlarges the definition: broad efficiency is the minimisation of waste throughout the economy or even society or the entire world. Just like scarcity, efficiency is manipulated by economic agents. For a company, firing workers may be efficient, but not for the economy as a whole, which sees itself confronted with rising unemployment. And, since means and ends are not fixed, efficiency has a dynamic meaning as well. So, investment may be costly now but makes production more efficient in the long run, for example through training workers or installing new software on office computers (and often through both).

Moreover, there are other economic values apart from efficiency, because economic processes go beyond simple means–ends relationships. These other values are important in themselves in social interaction, but may also have positive effects on efficiency. Such other values include fairness (if workers feel they are exploited they will not work diligently), trust (if a customer does not trust a supplier she will change shop), pride (which stimulates achievement), and equality (poor, unemployed people don’t have the money to buy the products offered for sale by those who have the capital to produce them). In short, as John Maynard Keynes phrased it in 1938:

Economics is essentially a moral science and not a natural science. That is to say, it employs introspection and judgments of value.2

And yes, we use numbers, mathematics, and statistics, in addition to rhetoric, stories, case studies, and logic, to do economics. Economics has a peculiar place in the social sciences: it is both abstract and moral, both quantitative and qualitative, and concerned both with human means and ends as well as with material processes and money flows. This brings us to the third and last key ingredient of economics, next to scarcity and efficiency: money. Real world economies use money. Money is anything that allows its holder to purchase goods. But lots of economic interactions do not use money: regulation, economic rights, satisfaction with achievements, innovation, trust, and, of course, unpaid work. So, money is a dominant measure used in economics, but it is not the only measure of economic activity, and often not the most important measure. Money is not an end in itself but is a fungible means: money allocated to school fees can easily be diverted to buy a bargain of a car. And as a means of accumulation, money leads to a perverse effect, namely, that some mistake it for an end in itself. But empirical studies show that high incomes and wealth correlates only very weakly or not at all with firm sustainability, economic stability, human development, or happiness.

Diagram 1.1 Gross National Happiness

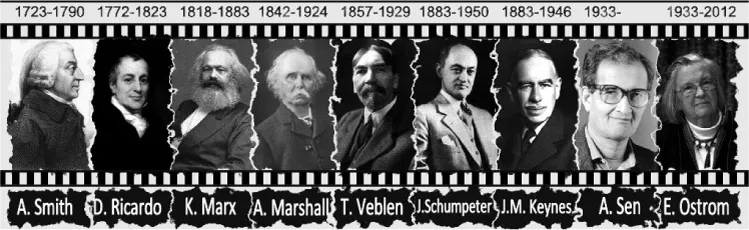

This textbook shows that economics is more than markets, money, and mathematics. This is illustrated by the contributions of the key economists in the history of economic thought. Their portraits are shown in Image 1.2. The annex to this book provides a brief overview of each of these economists’ contributions. In addition to these nine key figures, the annex also features three contemporaneous economists from the Global South who have helped make economics a truly global science.

1.1.4 Pluralism

Pluralism refers to the conviction that a plurality of theoretical and methodological viewpoints is valuable and contributes to the advancement of science. Since present views may be false, it is sensible to have a plurality of views available. And different social contexts may require different explanations: it is not always a matter of theories being wrong or right, but more or less adequate to explain certain phenomena in certain contexts. Pluralism is therefore a matter of open minds and ensuring a variety of perspectives. It involves recognition of variation in real-world economies; of the economic lives of men and women; of people living in rich and in poor countries; and of the functioning of markets as well as of states and the community economy. This sounds self-evident, but since one theory and its methodology has come to dominate economics since the 1980s, the majority of economists have been trained in this single view – neoclassical economics. A recent survey among American economists with a PhD degree has demonstrated that the great majority of them accept key neoclassical assumptions as the foundation of economics as a whole: economic agents as utility maximisers, having unlimited wants, and the importance of mathematical modelling.3

Next to neoclassical economics, we find a plurality of other theories and methodologies, also referred to as heterodox economics. For any theory, we can only determine its value by comparing it to other theories, so that by using them we learn which one works best for which type of problem under which conditions. And perhaps we will find out that some theories are far less applicable to real-world situations than others, across a variety of contexts.

Image 1.2 Nine key economists

In this book, I present the four key economic theories, ranging from the broad, less precise, and more connected to the real world to the specific and more abstract: social economics, institutional economics, Post Keynesian economics and neoclassical economics. These four theories are very much alive today, with their own journals, associations, policy think tanks, conferences, and research groups. I have chosen this mix of theories because they offer, I think, a wide and representative range of economic pluralism at the introductory level.