eBook - ePub

Learning to Write

First Language/Second Language

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1983. The present volume holds the selected papers of a symposium on CCTE Conference, held in 1979 in Ottawa, Canada. The content provides an introduction and a review of major themes in Writing research and pedagogy. This is in part achieved by the papers themselves, and in part by the introductions the Editors offer to each of the four Parts. Second, the reader is continually presented with a characteristic applied linguistic interplay of research and practice, each affecting the other, in a mutual and interactive manner. Third, the issues of 'Writing as Product versus Writing as Process', or 'The Teaching of Writing Skills versus the Development of Writing Abilities' or 'The Use of Writing for Learning and Knowing' are not merely issues affecting Writing alone but language learning and teaching as a whole, and one might add, the entire process of education.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

The writing process: three orientations

The writing process: three orientations

The study of writing has about it the aura and excitement of a discipline in its early stages of growth, yet interest in writing is, in fact, not new. There is, first of all, the long-standing tradition of conventional ‘composition’ teaching, which in one sense has fathered this new field of inquiry, but which bears little similarity to its progeny. A more congenial ancestry, however, can be found in a much older tradition — the centuries-long tradition of ‘rhetoric’.

Even before Aristotle, theorists and teachers were interested in analysing the process of producing discourse as well as its products in order, initially, to formulate a set of rules that might guide those learning the art. With Aristotle, this analysis was raised to a theoretical and philosophic level: the province of rhetoric was defined (as the area of contingent human affairs); its mode of reasoning was described (probabilistic judgements rather than the pure logic of mathematics or science); and the various parts of the rhetorical process were analysed, as was the interaction between speaker and audience. The study of rhetoric was clearly established as a scientific discipline, and the history of the classical period, in both Greece and Rome, shows that the art of rhetoric and the study of that art continued to seize the imagination of the most prominent thinkers of the time, reflecting both the significance of the art in practical affairs and the central role accorded the discipline by scholars and students.

During the middle ages and Renaissance, rhetoric continued to capture the interest of the best minds and to maintain its central position within the school system. In fact, its scope broadened to include not only the art of persuading but also the art of communicating in general, and increasingly written discourse became part of its sphere.

Gradually, however, its position was eroded. A significant blow was struck when Petrus Ramus, in his attempt to rationalize the school curriculum, appropriated what had been considered the first part of the rhetorical process — ‘invention’ — for the study of logic or thinking. Until then, the rhetorical process had been conceived to include not only the organization of ideas and their expression in the best possible words but also the discovery of those ideas — a broad conception of the process which the contemporary discipline of writing has restored. Ramus’ truncation and the subsequent narrowing of attention by rhetoricians to aspects of style ultimately led to the limited conception of the process associated with the term ‘composition’. The decline of the discipline was slow, but by the nineteenth century rhetoric had become composition, and by the twentieth century, the discipline was, in E.P.J. Corbett’s words, ‘moribund, if not door-nail dead’ (1967, p. 171).

This is not to say, however, that writing was not studied in the schools; for in the meantime, as suggested above, there had arisen that very limited tradition of composition teaching which is so familiar to all of us in first and second-language situations, with its emphasis on ‘correct usage, correct grammar, and correct spelling’, and its focus on ‘the topic sentence, the various methods of developing the paragraph … and the holy trinity of unity, coherence, and emphasis’ (Corbett 1965, p. 626).

Richard Young (1978) calls this tradition ‘current-traditional rhetoric’ and he argues that its practitioners’ emphases and pedagogic techniques were all determined by certain tacit but shared assumptions concerning the nature of the composing process. Chief among these was the Romantic conviction that the creative aspects of the process are mysterious, inscrutable, and hence unteachable. What can be taught and discussed are the lesser matters of style, organization, and usage.

In the 1960’s, those involved with the teaching of writing became increasingly dissatisfied with the current-traditional paradigm and began searching elsewhere for new pedagogic techniques and ultimately for a new explanation of the process. They turned both to the classical tradition of rhetoric as well as to such contemporary disciplines as linguistics, psycholinguistics, speech-act theory, cognitive psychology, sociolinguistics, and educational theory, in an attempt to come to a new understanding or at least to formulate appropriate questions for, and methods of, inquiry. And thus, the new discipline of writing has emerged over the past fifteen to twenty years, a discipline which can increasingly be characterized by its own sets of assumptions, its own preoccupations and characteristic strategies.

The first-language articles in this volume indicate some of the common interests and underlying assumptions which bind the new discipline. (For further analysis of the new paradigm, see Young 1978; Emig 1980; Freedman and Pringle 1980; Carroll 1980). First and understandably, there is an attempt to redefine its roots, a search for a more hospitable ancestry than ‘current-traditional rhetoric’. Commonly, as suggested above, contemporary rhetoricians point to the classical tradition as their appropriate heritage (see, for example, Bilsky 1956; Weaver 1967; Hughes and Duhamel 1962; and especially Corbett 1965), and many classical insights have been borrowed from antiquity and reinterpreted for use in contemporary contexts; for example, the division of the rhetorical process into five parts, with a focus especially on the first, invention; the three different kinds of appeal — an appeal based on the moral character of the speaker, an appeal based on logic, and one based on the audience’s emotions; and the effect in general of audience and the importance of context or occasion.

Besides the classical tradition, however, the new discipline derives much of its vigour from a very different source — from an extraordinary synthesis of many of the pervasive notions of twentieth century thought. In her important essay, Janet Emig (1980) identifies many of the figures of what she calls the ‘tacit tradition’, whose ideas have formed the unacknowledged matrix from which much current work on writing draws its vitality. Specifically, these include Thomas Kuhn, George Kelly, John Dewey, Michael Polanyi, Susanne Langer, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, A.R. Luria, and Eric Lenneberg.

This continuing attempt to find its roots, to locate an appropriate heritage, has been characteristic of the new discipline. Having rebelled so defiantly against the tradition into which it was born, it seems to feel a need to define its intellectual context by locating a more hospitable tradition.

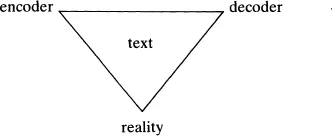

Another characteristic emphasis of the new rhetoric, one that reflects its radical departure from ‘current-traditional rhetoric’, can best be understood within the framework of the so-called communication triangle described by Kinneavy in Chapter 8. This model of discourse posits four elements in every communicative situation: the encoder or speaker or writer; the decoder or audience;the message or text; and the reality to which it refers.

As Abrams (1953) has pointed out in his analysis of literary critical approaches and Kinneavy (1971) in his discussion of discourse production, an analyst or producer of text may emphasize any one of the four different elements and further any of the many possible interrelationships. Widdowson, for reasons discussed below, insists on the primacy of the writer-audience relationship. Conventional composition teaching focussed on the message, the product, the written composition, analysing style, organizational patterns, rules of usage. The new rhetoric, in contrast, has consciously and deliberately shifted its focus to the encoder or writer, investigating especially the process of writing itself and the development of writing abilities within that encoder. (In second-language studies, these abilities may be relatively narrowly defined, but the focus is nevertheless very similar.) Thus many current thinkers have turned to the field of creativity theory for general insights into the creative process which might also cast light on composing. The four-stage model of the process described by Helmholtz (1903) and Wallas (1926) has been modified variously by contemporary rhetoricians (for example, Young, Becker, and Pike 1970; and Winterowd 1980), and considerable attention has been devoted to theoretic and pedagogic speculation about the first stage, the preparation, and especially to the kind of heuristic strategies that might be successfully employed by writers. Some have recommended contemporary versions of the Aristotelian topics (Wallace 1975), others have modified Burke’s pentad (Irmscher 1976), and Young, Becker, and Pike (1970) have developed a model based on tagmemic linguistics.

In addition to borrowing from research done in the field of creativity theory, however, those involved in the study of writing have developed an indigenous tradition of research on composing. With her seminal study, The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders (1971), Janet Emig was the first to attempt to investigate the writing process scientifically and systematically. Basing her analysis on tape-recorded pre and post-writing interviews as well as on transcribed composing-aloud sessions, Emig focussed on eight twelfth-grade students engaged in several distinct writing tasks. More recently, Sondra Perl (1979) has refined this methodology in order to explore the composing behaviours of unskilled college freshmen, while Flower and Hayes have been accumulating a massive library of what they call ‘composing-aloud protocols’, that is transcripts of writing sessions where subjects are asked to record every thought that comes to mind during the writing process. On the basis of a painstaking analysis of the transcripts of both professional and apprentice writers, Flower and Hayes have developed a powerful model of the conscious processes involved in writing.

At the same time, researchers such as Pianko (1979) and Matsuhashi (1979) have employed a different methodology: they have videotaped their subjects while they write, without any requirement that they compose aloud. After each session, they review the tapes with the writers, probing for information concerning what went on in their heads at crucial points. Characteristic behavioural sequences have thus been identified, and pauses have been measured and correlated with grammatical and rhetorical units to glean other kinds of insight into the nature of the composing process. Jones (1980a, b) has initiated the study of the writing processes of ESL students using the same techniques.

This characteristic focussing on the composing process is represented in this volume by the essays of Britton (Chapter 1) and of Bereiter and Scardamalia (Chapter 2). Each of the two essays goes beyond reporting on research, although both emerge out of large-scale projects investigating writing and its development. Beyond such research, however, Britton’s work comes out of long observation of children and discussions with teachers eliciting their observations; he draws as well on that rich intellectual context defined by Janet Emig as the ‘tacit tradition’, and in his work Britton exemplifies the wedding of abstraction with experience, the continuous interplay between intellectual generalizations and the rich texture of reality that he and the school of British educationists he is part of declare to be essential for real knowledge of the world.

Bereiter and Scardamalia, in contrast, are cognitive psychologists whose speculations in the essay included in this volume are based primarily on the results of a large-scale, long-term research project involving a great number of carefully conducted, specifically designed experiments with children in the elementary and secondary years. The subjects of these experiments were sometimes involved in conventional writing tasks, but more frequently performed carefully constructed tasks designed to reveal the kinds of cognitive strategies they had available to bring to the writing task at particular points of their development. For example, instead of being assigned a topic for a short story, pupils were asked to write a story that would conclude as follows: And so, after considering the reasons for it and the reasons against it, the duke decided to rent his castle to the vampires after all, in spite of the rumour he had heard. In another typical experiment, pupils were asked to write on an argumentative topic and, when they announced they were finished, were simply asked to write more — again and again. Such an assignment revealed that even after the children felt they had completed the task, they still had more to say on that topic and, though it seems bizarre, were quite happy to be asked to do so. Bereiter and Scardamalia have used such experiments to reveal the kinds of cognitive strategies children need to acquire in order to learn to write. The theorizing about the nature of the composing process presented in the Bereiter and Scardamalia essay in this volume is based on the findings of many experiments of this kind.

Although at first reading the language (and certainly the terminology) and approach of the Bereiter and Scardamalia essay seem radically different from that of the Britton essay, and although the starting-point and certain of the implications of their arguments are clearly different, if not diametrically opposed, beneath the differences we can perceive some of the common factors that bind the discipline. Both essays reveal a distrust of much that takes place in conventional composition classrooms and that is presented in traditional texts. Both focus their attention, as we have said, on the person composing rather than the composed product, and both place an extraordinarily high value on what this process can do for the writer especially in his relations to reality, his world-view.

Some of the differences between the essays, however, are worth dwelling on as they suggest different paths within the discipline. Britton bases his discussion on what he sees as the potential similarities between speaking and writing, arguing that we should be able to transfer the spontaneous inventiveness of speech to writing. ‘Successful writers adapt that inventiveness [from spontaneous speech] and continue to rely on it rather than switching to some different mode of operating’. Bereiter and Scardamalia, in contrast, point to the fundamental differences between conversation and composition and argue that much of the difficulty involved in learning to write derives from the fact that in order to write we must learn a whole new set of cognitive strategies that are not called for in the production of oral language.

What appears to be a more fundamental opposition, however, turns out to be more apparent than real. Bereiter and Scardamalia make a distinction between two kinds of composing: the low road and the high road. At first glance, the low-road writing seems remarkably similar to the ‘shaping at the point of utterance’ that Britton advocates. Certainly, what Bereiter and Scardamalia say about the ‘running jump strategy’, sounds reminiscent of Britton’s Newcastle boy’s introspective comments. ‘The running jump strategy … consists of rapidly rereading the text produced so far and using the acquired momentum, as it were, to launch themselves into the next sentence’. The Newcastle boy explains his process thus: ‘It just comes into your head, it’s not like thinking, it’s just there. When you get stuck you just read it through and the next bit is there, it just comes to you’.

A closer analysis, however, reveals that what Britton is advocating is not what Bereiter and Scardamalia call ‘knowledge-telling’, the simple emptying of one of our memory file holders. Britton describes shaping at the point of utterance thus:

shaping at the point of utterance involves … drawing upon interpreted experience, the results of our moment by moment shaping of the data of the senses and the continued further assimilation of that material in search of coherence and pattern; and secondly seems to involve by some means getting behind this to a more direct apperception of the felt quality of ‘experience’ in some instance or instances; by which means the act of writing becomes itself a contemplative act revealing further coherence and fresh pattern.

And he quotes at length Perl and Egendorf (1979), who talk about the writer’s continual shuttling back and forth between the non-verbal sense of what they want to say and the words on the page. Bereiter and Scardamalia describe children on the high road as those ‘who start to think about what they are writing down on paper as having relations to various other things in their minds. Most importantly, they may begin to see that there is a relationship, and not necessarily an identity, between what they write and what they mean...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- The Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One: The writing process: three orientations

- Part Two: The development of writing abilities

- Part Three: Text and discourse

- Part Four: Implications for teaching

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Learning to Write by Aviva Freedman,Ian Pringle,Janice Yalden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.