eBook - ePub

Hospital Policy in the United Kingdom

Its Development, Its Future

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hospital Policy in the United Kingdom

Its Development, Its Future

About this book

Harrison and Prentice aim to provide a source of reference and reflection for those who are concerned with the planning of hospitals themselves or who are concerned with the health care delivery system as a whole. The authors set out a detailed framework for analyzing hospital services in relation to other providers, based on clinical quality, costs of provision, and access. The book also contains a series of recommendations for action.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hospital Policy in the United Kingdom by Anthony John Harrison,Sally Prentice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The development of hospital policy

When the National Health Service (NHS) was established, it inherited a collection of hospital assets which no national health authority would have invested in, had one existed before the war. Surveys both before and after the Second World War identified large variations between different parts of the country in the quality and the quantity of provision. A third of consultant staff were located in London and some parts of the country, such as what is now the Anglia and Oxford Region, had virtually none. In other areas, facilities were duplicated as a result of parallel developments by local authorities and voluntary bodies.

Economic difficulties in the immediate post-war period ruled out any immediate rationalisation and modernisation. It was not until the 1960s that a serious attempt was made to reshape those assets into a national system of hospital provision. The 1962 Hospital Plan for England and Wales, and its counterparts for the other parts of the UK, represented the first national attempt to provide an acceptable standard of hospital services across the country as a whole. According to Webster (1988):

The major innovation of the National Health Service was its state-owned and exchequer-funded hospital service. For the first time comprehensive hospital and consultant care was made available to all, and without imposition of direct charges. Inadequacy of specialist services was the most glaring defect of the inter-war system of medical care. Alleviation of this defect was a primary incentive for the first tentative moves towards a national hospital plan. (p257)

The aim of the Plan (Ministry of Health, 1962) was:

to give to the hospital service of England and Wales both the physical equipment and also the pattern and setting which will everywhere place the most modem treatment at the service of patients and enable the staffs who care for them to exercise their skill and devotion under the best conditions, (piii)

The Plan proposed that each district of around 100-150,000 people should have a hospital – known then, as now, as a district general hospital or DGH – in which all but a few specialties – radiotherapy, neurosurgery and plastic surgery which would be provided at only a few sites – were represented. Within this vision of the future, small hospitals were to be retained, particularly in less densely settled parts of the country, where distances to the nearest district general hospital would be too great.

Thus the hospital service on this model would be in three tiers, with the vast majority of work done in the middle one, the district general hospital. The ‘higher’ tier would contain more specialised facilities, and obtain patients by onward referral from DGHs: most research and teaching would be carried out in such referral institutions which would normally also provide DGH services as well. The lower tier would provide a very limited range of facilities, such as care for the elderly.

After 1962, a number of planning documents appeared in which different views were put forward as to the desirable size of catchment area for a district general hospital on the one hand, and the role of the smaller hospital on the other. In 1969, the Bonham-Carter Report The Functions of the District General Hospital (DHSS, 1969) reaffirmed the notion of a general hospital, dismissing the development of separate hospitals for children, women, accidents or orthopaedics. It argued that the 1962 Plan had understated the case for concentrating medical resources and hence proposed that the average hospital size should be much bigger. Whereas the 1962 Plan had proposed catchment populations of some 100-150,000, the Committee suggested that these figures might be doubled. Given the lengths of inpatient stay then current, that meant hospitals might contain some 1,500 beds. That view did not win general support; the Bonham-Carter Report had only a modest impact on the physical size of hospitals. Few hospitals with more than 1,000 beds were ever built.

Although the 1962 Plan and the Bonham-Carter Report endorsed the notion of general hospitals providing a comprehensive service, they also allowed a role, if a modest one, to other kinds of hospital. As the Plan put it:

But many small hospitals will still be needed. Some will be retained as maternity units, though any additional provision will nearly always be at the district general hospital. Others will provide long-stay geriatric units. Others again, where a local population is remote or inaccessible, or where isolated towns receive an exceptional seasonal influx of visitors, will continue to admit medical emergencies which do not require specialist facilities. Finally, though this is not indicated in detail in the plan, many small hospitals where no beds, or at least no acute beds, need eventually be retained will be suitable for providing out patient services. (para2.5)

Later reports continued to promote the role of the small hospital. Circular DS 85/75 (Department of Health, 1975) proposed that most hospital services should be based on general and community hospitals: the latter were to have between 50 and 150 beds – much larger than most of the existing small institutions – and were to be run by general practitioners under the general oversight of consultants. The Royal Commission on the NHS (DHSS, 1979) suggested that up to one quarter of all inpatient beds might be in community hospitals.

A year later, a Consultation Document, The Future of Hospital Provision in England (DHSS, 1980) reaffirmed the validity of the district general hospital, while suggesting that some such institutions were too large:

Experience has shown that a large degree of concentration on a single site may in itself have serious disadvantages. Communications of all kinds within the hospital become more complex and difficult, as does management. Patients and relatives, as well as staff, find the hospital too impersonal. It often suffers from physical disadvantages and the need to provide air-conditioning, with high energy requirements, (p 10)

It then went on to point to other disadvantages:

Steep rises in motoring costs means that travel to hospital is more expensive for patients, staff and visitors. Ambulances and other forms of hospital transport all cost more to run. Public transport costs more. And in rural districts it is not as comprehensive, nor as frequent, as it used to be – an important factor for many elderly patients and mothers with young children, (p 11)

Accordingly, it proposed that the policy of concentration should be changed by placing less emphasis on the centralisation of services in very large hospitals and hence allowing a wider range of local facilities to be retained. It argued that small or medium-sized hospitals would continue to have a role, partly on access grounds both for patients and staff and partly to relieve pressures on the main hospital which, it argued, might become too large and hard to manage if all services were concentrated on one site.

Since 1980, the Government has published no general statement about what the form and content of district general hospitals should be, despite the scale of its commitment to building or refurbishing the existing stock. It has been left to Regional Health Authorities to form their own strategies in the light of the resources likely to be available to them and to guide district health authorities through their control over capital allocations.

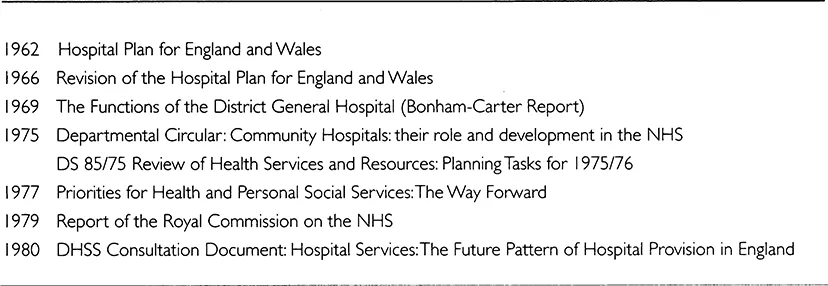

Table 1.1 Hospital planning: key dates and publications

The current pattern of hospital provision is far from conforming to the 1962 blueprint: there is a smaller number of beds doing more work as medical technology has allowed more work to be done in fewer beds than was then envisaged. As a result, although there are many fewer hospitals now than there were then, the size of district general hospitals measured in terms of beds has not risen.

Economic factors, too, have influenced the way that the Plan was implemented. The so-called IMF crisis in the mid-1970s led to major cutbacks in the hospital building programme and the 1980 Consultation Document made it clear that planning had to proceed on a piecemeal basis. To assist with this, the Department developed the nucleus hospital modular design which allowed capacity to be added in incremental but compatible stages. Furthermore, the Consultation Document recognised that in practice the district services might be spread over more than one site since the capital funds to unify them might not be available. In this way, the district general hospital became, and in some way remains, an organisational concept applied over separate sites rather than a single cluster of related clinical activity.

Nevertheless, despite the impact of economic and technological factors, the district general hospital has remained the guiding idea for hospital development up to the present day. Although opinions have altered as to how large, and precisely what its range of activities should be, the idea of a single hospital or, in the case of split sites, a single management unit, serving the majority of the health needs of a district – or part of one in some parts of the country – has remained influential, both in plans for new or replacement hospitals, as well as plans for the configuration of existing facilities. All districts in England contain a DGH and in Wales only rural Powys relies on services provided outside its own district for acute hospital care.

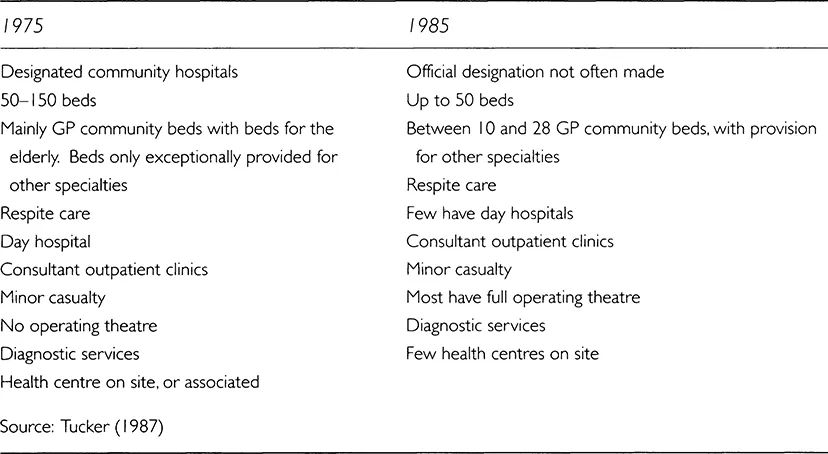

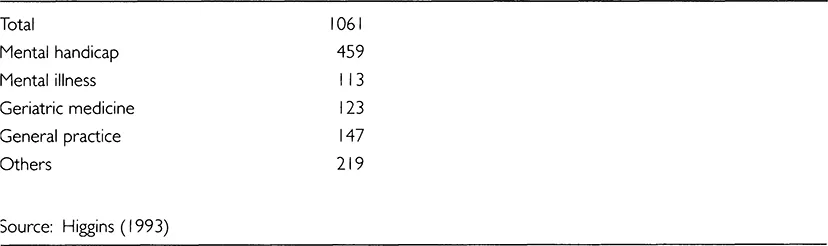

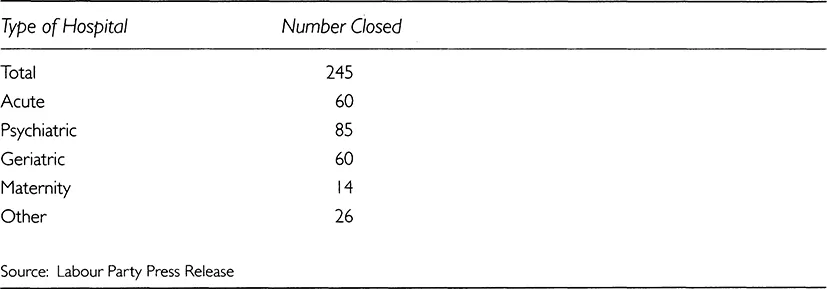

Despite the support offered in the various official reports listed in Table 1.1, the small hospital has not, except in a few parts of the country, retained or achieved the position in the health care system envisaged for it in the 1970s. Community hospitals are typically much smaller but carry out a similar range of functions to those envisaged in the 1970s: see Table 1.2. In addition, there were, as late as 1989, a large number of small hospitals caring for particular care groups: see Table 1.3. Since then, following the creation of trusts, official figures do not identify individual hospital sites. But in May 1995, the Shadow Secretary of State for Health, Margaret Beckett, drawing on figures obtained by the House of Commons Research Division, revealed that 245 hospitals had been closed between 1990 and 1994: see Table 1.4. Most of these were institutions specialising in the care of particular groups of patients. During the same period, a handful of new hospitals were opened, most replacing or modernising existing facilities.

Table 1.2 Comparison of current provision with the original DHSS guidance HSC(IS)75

Table 1.3 Small NHS hospitals, England 1989/90

Table 1.4 Hospital closures, England 1990-1994

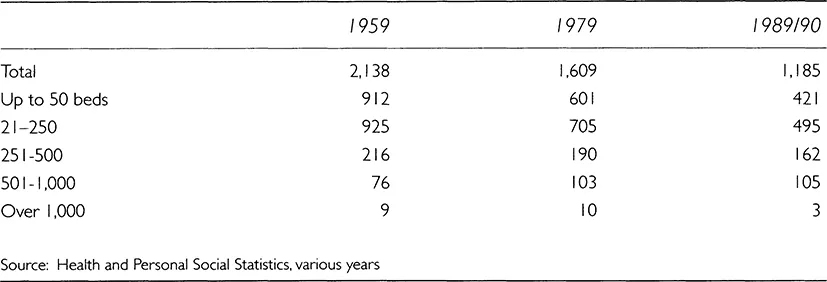

As Table 1.5 shows, the number of small hospitals has fallen, as has the number of very large units, while numbers in the middle ranges have risen in absolute terms and as a proportion of the total. According to Higgins (1993), the events of the 1980s marginalised the role of the small hospital so while a number of reports appeared on what their role might be, no national level response has been forthcoming. Instead Regions have gone their own way: some, particularly the more rural ones, aiming to retain smaller hospitals, others seeking to close down such units and consolidate all activities into central sites. As a result, some areas of the country retain a network of small hospitals carrying out some of the functions to be found elsewhere in general hospitals; in others, they have virtually disappeared.

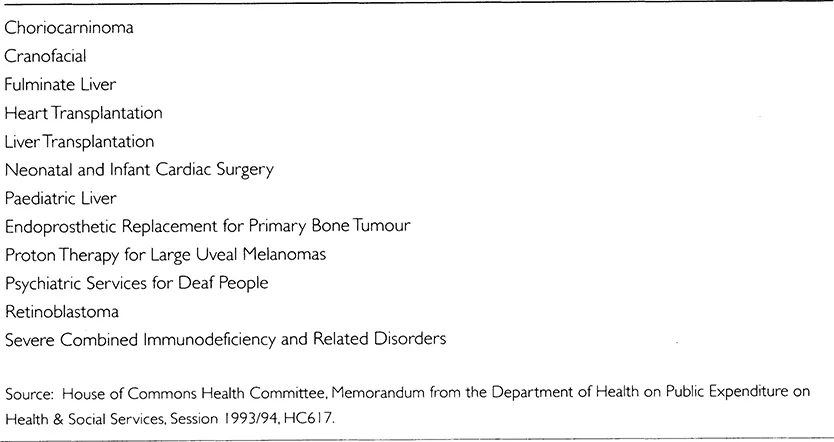

At the other end of the scale, some services such as neurosurgery and plastic surgery are only available in a few hospitals, so patients needing them must travel outside their district. Typically, they are to be found in teaching hospitals, but elsewhere energetic physicians have been able to develop specialised services within DGHs. In a few instances, the so-called supraregional services, the Department of Health has intervened to ensure their availability by channelling finances directly to them. The criteria for obtaining this privileged financial status were set out in Health Circular (83)36 as follows:

Table 1.5 Number of non-psychiatric hospitals: England

... services which, in order to be economically viable or clinically effective, need to be provided for a population substantially larger than that of any one Region.

The current supra-regional specialties are shown in Table 1.6.

Table 1.6 Supra-regional specialties

Thus the English hospital system is a hierarchical system, but it is not a uniform one. The differences to be found between different parts of the country stem partly from geography and the accidents of history. They also stem from a lack of clarity as to the appropriate division of roles between the different tiers. For example, although plans for a national system of cancer care were formulated before the foundation of the NHS, similar proposals for a hierarchical system of care were put forward by an expert committee in 1995 in the light of evidence that patients were not being referred to the specialist services their needs required. Similarly, a report by the Clinical Services Advisory Committee (1994) presented evidence that access to specialist heart surgery varied widely between different parts of the country. In these and other services for which DGHs may not be the appropriate place of care, there has been no national policy to ensure a similar level of availability throughout the country. The same is true for services within DGHs. A recent stud...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The development of hospital policy

- 2 Why general hospitals?

- 3 Systems of hospitals

- 4 Hospitals and other providers

- 5 Scale, scope and clinical quality

- 6 Scale, scope and costs

- 7 Access

- 8 The demand for hospital services

- 9 The supply of hospital services

- 10 Access: prospects and policies

- 11 What should be done?

- Annex

- Bibliographical notes

- Bibliography

- Index