![]()

1

WE THE PEOPLE

Systemic and ideological contradictions, as well as tensions between a diverse range of contemporary responses to the US Constitution and the broader context of American democracy, were identified as the central themes for We the People: The American People and Their Government, an exhibition developed by the National Museum of American History for the American Bicentenary commemorations in 1976. We the People focused on cultural politics as well as the culture of politics in order to address a wide variety of opinions about the role of government in society. It put into exhibition form what political scientist David McKay (2009: 16) has called the ‘most important feature of the American political culture’, which is its ‘ability to accommodate apparently deep divisions over the role of government in society, without challenging the constitutional order or what many have defined as “Americanism”’. Visitors to the exhibition would have been expected to have a response similar to that expressed by a first-time (Canadian) visitor to the US, who recalled: ‘it wasn’t the idea of exceptionalism that I discovered in ’68 …. It was a hundred sects and factions, each apparently different from the others, yet all celebrating the same mission’ (cited in McKay, 2009: 17).

In addition to seeing this contemporary diversity reflected in the exhibition, visitors were encouraged to understand that historically a generally strong expression of support for the US Constitution and high public expectations of the democratic process have existed alongside an attitude of considerable disillusionment with particular processes and institutions that is reflected in a widespread preference for a limited, or ‘small’, government. According to a Smithsonian Institution press release announcing the exhibition’s upcoming opening:

We the People will be a history of American government in three parts – ‘Of the People’ asking who we are and have been in census, symbol and association with the rest of the world; ‘By the People’, how we campaign, vote and influence our government, and ‘For the People’, how our system of government assures our health, education and general welfare, responding to objectives established in the Constitution of the United States. The exhibit will open in early Spring, 1975.

(Smithsonian Institution Office of Public Affairs, 1975b)

We the People was displayed at the National Museum of History and Technology (in various forms) from 1975 until 1995. At 20,000 square feet and costing over US$900,000,1 it was a large and high-profile exhibition that hosted between 2000 and 6000 objects throughout its lifetime.2 The dynamism, topicality and political engagement of We the People was emphasized by newspaper reports of the formal opening of the exhibition, which was held to honour the incoming members of the 94th Congress. The event was attended by a raft of other political players as well, and guests included Mayor Walter Washington, who had been elected that same year as the first home rule mayor of the District of Columbia. We the People also played a key role in consolidating an identity for the relatively new museum, which had opened in a state of the art building on the National Mall a decade earlier, in 1964. This chapter explores how the aims of achieving political engagement and experimenting with emergent museological practices were progressed through the development and design of this exhibition.

Dedicated to provoking a conversation about political culture, We the People encouraged its visitors to consider the relationships that exist between museums, ‘the people’ and various levels of government. The exhibition presented museums as an important component of political culture on the grounds that they were shown to be institutions that are supposedly independent of the influence of political authority and committed to representing the diversity of the American experience.3 It was also an acknowledgement of the role that the Smithsonian Institution (created through legislation passed in 1846) had played in the period since American Independence, and demonstrated the ongoing influence of previous Smithsonian employees, including George Brown Goode. A natural historian, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in charge of the United States National Museum from 1885 (Kohlstedt, 1988; United States National Museum, 1892) and a proponent of the ‘modern museum idea’ (that he also called the ‘new museum idea’), Goode was a staunch advocate of the idea that museums had the capacity to provide places of public education and social reform (see Goode, 1894; 1895: 71–72; 1889: 268).4

Goode understood ‘scientific’ institutions such as the Smithsonian as functioning in ways analogous to the US Constitution in the sense that both provided a ‘conservative yet flexible frame of mind’ (Belz, 1969). Sally Gregory Kohlstedt, a biographer of Goode, has argued that he ‘appreciated a political historiography which stressed interest groups, leadership, power, and cultural federalism because these concepts applied readily to the scientific institutions he chose to study’ (Kohlstedt, 1988: 20). Goode’s adoption of what we might today call a ‘utility of culture’ approach, whereby government sponsorship was seen as an appropriate way to advance science, was not universally supported by his contemporaries. Questions of political interference (and the Smithsonian’s obligations to Congress) have also continued to be an issue for the Smithsonian Institution (which I address subsequently throughout this book, and specifically in relation to The West as America in Chapter 5). We the People’s debt to Goode, however, was more closely aligned with his commitment to the more independent political dimensions and activities of the National Museum, which he clearly recognized as an activist institution capable of generating social and intellectual outcomes within the broader community. In an essay called ‘The Museum of the Future’, Goode reflects that comments made by Sir Henry Cole, founder of the British Department of Science and Art, are ‘as applicable to America of to-day as to Britain’:

If you wish your schools of science and art to be effective, your health, the air, and your food to be wholesome, your life to be long, your manufactures to improve, your trade to increase, and your people to be civilized, you must have museums of science and art, to illustrate the principles of life, health, nature, science, art, and beauty.

(United States National Museum, 1892: 431)

We the People positioned national museums (as its particular focus) as active agents capable of articulating the complexity that is associated with the relationships between the Smithsonian, political authority and the experience of everyday Americans. Setting aside the historical connection between museums and the colonial enterprise (which I address through other chapters, particularly Chapters 3 and 4), museums, like universities, have often been considered bastions of independent liberal thought, where intellectual freedoms (and open communication which aims to make knowledge widely available) are to be protected as fundamental public goods. Museums have often similarly been funded through public funds or state appropriations, and held accountable to generic outcomes similar to those articulated by Cole (above) that are, despite being difficult to define and assess, commensurate with key public missions, such as increased public access, the education of civil servants and teachers (as well as children), and the production of research solutions for problems of national need (Rhoten and Calhoun, 2011: 4).

Certainly, it was a sense that obligations arising from the structural and financial patronage of the Smithsonian Institution by the US Congress had been contravened that contributed to the role that museums played in the history wars of the 1980s and 1990s. The difficult and often historically entangled imbrications of museums and governments and the ongoing debates over the intellectual freedoms and responsibilities of curators and researchers were also important elements of the earlier context in which We the People was developed. And while the political aspirations of We the People may have been more modest than those articulated by Cole and singled out for praise by Goode, the curators nonetheless identified the exhibition as an important way to communicate changing public ideas about topical issues such as the youth vote (which was legislated in 1972).

In addition to its intention to address and engage with the socio-political context in which the museum operated, We the People represented a particular museological moment that was responsive to increased levels of interest by the general public in the condition and nature of contemporary relationships between Americans and their government. This means that while the centrality of the US Constitution to the exhibit emerged from the requirement to commemorate the US Bicentenary, it also provided a platform from which to explore connections between government, government agency and authorities, mainstream and marginal populations, and citizenship practices (including protest and reform movements). Importantly, the exhibition presented the museum as a central enabling agent in the transactions occurring across these sectors. This theme is the main focus of both this chapter and the next one, in which I contend that the exhibition consciously and successfully conveyed the idea that museums can function as institutions that both (and simultaneously) represent and challenge dominant ideas about political nationalism. The exhibition was also proactive in declaring the contribution it made to different understandings of key terms and experiences, including citizenship and belonging. I explore this proposition by analysing the ways in which We the People represented (often emotive if not contested) contemporary socio-political events, and by investigating the approaches employed by curators who had to build additional material collections for the exhibition. I also explore various responses to the exhibition as recorded and acted upon by the Division of Political History.

FIGURE 1.1 Youth vote display at The Right to Vote exhibit, 1972–1974

Source: Division of Political History Collection, National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image 72–10834

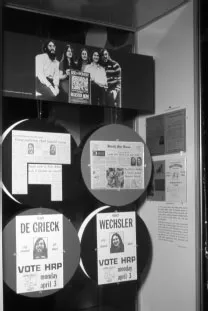

The second section of this chapter contextualizes We the People more broadly in relation to the development of the Museum of History and Technology. The actions leading up to the opening and naming of the new museum in 1964 gave a new prominence to the field of American history and drew attention to changing ideas about the purpose and function of museums. This meant that many of the approaches and innovations featured in We the People were logical extensions of practices and strategies that had been explored by curators and designers in the creation of the new Museum of History and Technology building and opening exhibits. We the People’s emphasis on political reform movements and protest had, for example, been features of the previous Human Rights Commemoration exhibition (1968) and The Right to Vote exhibition (1972–1974). Curatorial approaches employed in these earlier exhibitions had signalled a sharply increased interest in the incorporation of new technologies and ideas about ergonomics and building use. New techniques also embodied a heightened awareness of the educational remit and public outreach programme of the museum, and demonstrated growing interest in what the Museum of History and Technology’s first director, Frank Taylor, referred to as the ‘exhibit function’.In the final instance, We the People and its particular treatment of the political history of America can only be understood through an investigation that moves beyond the exhibition’s connections with America’s bicentenary celebrations. Specifically, it needs to be explored in relation to the changing socio-cultural and political landscape outside the museum, and in relation to the history of the development of the Museum of History and Technology (and Division of Political History) in the years leading up to the opening of the museum.

FIGURE 1.2 The Right to Vote exhibit installation, 1972–1974

Source: Division of Political History Collection, National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image 72–10827

The Museum as a space for dialogue between ‘the people’ and ‘their government’

Despite the exhibition’s main function of delivering nation-building activities for the American Bicentenary commemoration, and the more incidental role it played in defining an identity for the museum, We the People has not been the subject of academic analysis. My initial plan for studying the exhibit was to approach the institutional records of the Museum of History and Technology (now called the National Museum of American History) and the Smithsonian Institution to investigate the image of nationalism and citizenship that was conveyed by the exhibition. However, I soon recognized that We the People produced a more complex and nuanced understanding of the relationships between politics (the state), culture (the national museum) and a diverse constituency (including marginalized populations) than can be understood from a straightforward consideration of the exhibition’s national significance. The exhibition’s sophistication resulted from the ability of curators to balance the centrality of the US Constitution against the current and historical socio-political events that the displays both documented and reflected.

We the People presented the dialogue between ‘the people’ and ‘their government’ (as a contemporary as well as historical set of negotiations) in order to facilitate audience discussion about the legal rights and responsibilities, as well as the lived experiences and challenges associated with American citizenship as formalized in the Constitution.5 While it had a lot in common with The Right to Vote exhibit (which I discuss in the last section of this chapter), as the exhibit that immediately preceded it and that most closely related to its focus on political petitioning, reform and popular protest, We the People sought to engage with and represent a more challenging and less legalistic understanding of citizenship. Unlike The Right to Vote, which had focused on both the apparatus of formal citizenship (ballot boxes and voting machines), and the outcomes (rather than the process) of constitutional amendments pertaining to citizenship, We the People emphasized the ways in which citizenship is understood and experienced informally.

FIGURE 1.3 The Right to Vote exhibit, 1972–1974

Source: Division of Political History Collection, National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image 72–10833

The exhibition’s attention to contemporary and historical grassroots political reform movements, as well as institutional (legal and juridical) elements of American citizenship indicates that We the People did not simply produce a morally instructive or aspirational experience that sought to inform visitors how to be better Americans. In addition to illustrating debates between ‘the people’ and ‘their government’, the exhibition’s focus on the US Constitution effectively brought culture – that is, the museum itself – into the mix as an additional and active agent that both contributed to and is affected by negotiations over people, place and belonging, as topics which are often at the heart of debates over citizenship and nationalism.

In certain circumstances the museum, under the stewardship of its curatorial and management staff, became an advocate for particular causes (Mayo to Clayton, 24 May 1974a).6 This investment led to claims of partisanship on some occasions from members of the general public (for example, a complaint that all the protest exhibitions in We the People ‘were from the left’ (Stevens, 1979)). Responses such as these demonstrate that We the People did not simply represent the debates and dialogue between the national government, the national museum and the American people who are represented by both. Instead, it was unique in its ability to provoke such discussions from time to time. The emphasis on dialogue that was apparent in the curatorial approach to collecting and representing contemporary socio-political events built on the ideas of individual curators. It also reflected the interests of senior staff within the organization, including the first director of the Museum of History and Technology and S. Dillon Ripley, who became secretary of the Smithsonian Institution shortly after the Museum of History and Technology opened in 1964 (he held the post until 1984). These staff b...