![]()

CHAPTER 1

A short history of British magazine publishing

Christine Stam

In these early years of the twenty-first century colourful magazines are everywhere. We see them in newsagents, in supermarkets, on buses, trains, aeroplanes and anywhere readers have spare time to enjoy them. They entertain us, enlighten us, challenge us (occasionally), sometimes anger and frustrate us. Printed weeklies, monthlies and quarterlies make a popular contribution to the culture of Britain today; many would argue that a world without print-on-paper magazines would be a dull place indeed, whatever the trend towards digital editions might bring.

…a world without print-on-paper magazines would be a dull place indeed, whatever the trend towards digital editions might bring

King William III and his wife Mary were on the throne in 1693 when The Ladies Mercury, the very first weekly ‘periodical’ aimed specifically at women was introduced. Printed in London on two sides of a single sheet of paper, it promised to address the issues of ‘love, marriage, behaviour, dress and humour of the female sex, whether virgins, wives, or widows’. It lasted four weeks but began an industry that expanded rapidly in the nineteenth century, thrived in the twentieth century then began its diversification in the twenty-first century. Today, in the age of digital publishing and the internet, the printed publication might be considered a dying artefact. Will the reign of a future King William see the end of magazines as we currently know them?

This chapter investigates the evolution of magazines during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries and aims to show how such an inexpensive, everyday item affected the sociocultural makeup of a nation. In turn, magazines themselves are heavily influenced by the society of the day. It will show how a publication which starts to become out-of-date as soon as it leaves the printing press, by necessity, must foreground the social and cultural ethos of the moment. We will see how the development of transport and communication systems impacted on distribution channels and how technological developments have consistently affected the industry.

In simple terms, the UK magazine market may be divided into three areas:

■ consumer

■ business (also known as trade, professional or B2B)

■ customer (contract or custom).

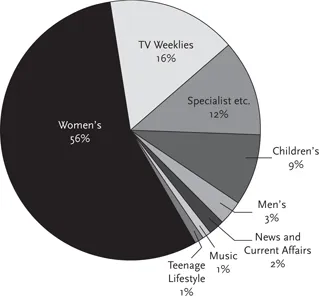

Figure 1.1 Consumer magazines: revenue market share

Source: Adapted from Marketforce ABC Market Summary Report (Jan–June 2012)

Suffice to say here that consumer, or mass publishing holds by far the greatest market share today: women’s titles being the dominant source of revenue. The tradition of these reaches farthest back into the past and therefore this chapter will be dominated by the magazines that the general public read. Although B2B and customer publishing are included, their significance is discussed in greater detail elsewhere in this book.

IN THE BEGINNING (1731–1838)

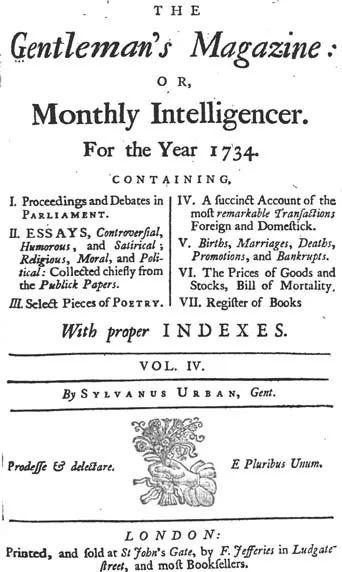

Although various forms of printing onto paper and material have been around for thousands of years, the German Johannes Gutenberg is credited with the invention of the first workable, movable type, printing press in the 1440s. William Caxton brought the technology to England in 1476, setting up a printing press in Westminster and producing the first mass copies of books such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It took a further 250 years, however, before the first printed magazine appeared. The Gentleman’s Magazine was founded in London by Edward Cave in 1731, surviving for almost 200 years, until it finally closed in 1922. Cave coined the nomenclature ‘magazine’ for his publication after the French magasin, meaning ‘warehouse’ (originating from the Arabic makhazan) and, unknowingly, generated the modern industry of today. His was a monthly digest of commentary and news on any topic in which the educated public might be interested: from parliamentary debates to ‘select pieces of poetry’. Prior to his innovative and perhaps accidental introduction, specialised journals and transitory periodicals, such as The Ladies Mercury, had existed but had failed to capture the imaginations of the public at large.

Photo 1.1 Edward Cave’s eighteenth century The Gentleman’s Magazine was the first printed publication to use the term ‘magazine’

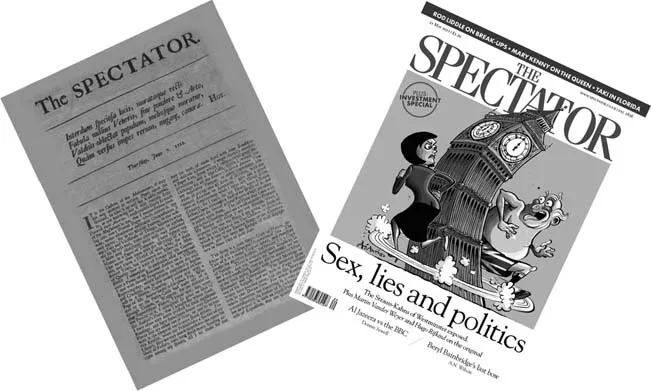

During this period, one of the most significant advances in printing technology became available. Lithography was developed in Germany by Alois Senefelder in 1796 and the basic principles of this 200-year-old method are still used today in the production of most magazines (see Appendix 1). Other examples of the deep-rooted historical nature of the magazine industry may be seen in the titles introduced in the eighteenth century. In 1709 Richar Steele founded a literary and society journal, calling it The Tatler. Two years later, after the closure of this enterprise, Steele went on to co-found another periodical, The Spectator which catered to the emerging middle classes. While neither of these august publications are the direct ancestors of today’s titles through uninterrupted lineage, they are good examples of how magazines decline and die, only to metamorphose and evolve in future generations.

During the latter half of the eighteenth century the ‘magazine’ format, with its miscellany of content and consistency of availability, became more widely adopted. Women’s periodicals adapted to the changes and their numbers increased, with more than a score of these new types of publications appearing before the end of the century. The most notable of these were The Lady’s Magazine (1770–1837) and The Lady’s Monthly Museum (1798–1832); two publications upon which many of the early Victorian women’s periodicals were modelled.

Photo 1.2 Three hundred years of The Spectator magazine. Richard Steele and Joseph Addison’s original version of 1711 and a recent cover from the modern publication (2011)

The Spectator

■ Co-founded by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison, the first title by that name appeared in 1711. Published six days a week (excluding Sunday) it offered comment and opinion on matters of the day. It ran for 555 issues until December 1712. Each copy was about 2,500 words and it had a print run of approximately 3,000 but a readership in the region of 60,000, due to its popularity in the London coffee houses. (Today’s online blog, Coffee House, harks back to the early history of the magazine.) The magazine was aimed mainly at the interests of England’s tradesmen and merchants. While claiming to be politically-neutral, it did, in fact, espouse Whig (predecessors of the Liberal Party) values.

■ The title was revived for six months in 1714.

■ On 5 December 1828 Robert Rintoul, a liberal-radical, launched the modern The Spectator insisting, as editor, on having total power over its content. Thus began the tradition of the paper’s editor and proprietor being one and the same person; an arrangement that lasted into the twentieth century.

■ The Spectator is now the oldest continuously published magazine in the English language. It is published weekly and has a circulation of about 64,0001. (Not so very different to the original readership in 1711.)

■ Over the years the political leaning of the magazine has been influenced by the editor/proprietor. In the latter half of the nineteenth century it gradually became more conservative; then reverted to liberalism in the early twentieth century. Editors in the latter half of the twentieth century indicate the political direction the magazine took: Ian Gilmour (1954–59), Ian Macleod (1963–65), Nigel Lawson (1966–70), Boris Johnson (1999–2005), all prominent Conservative Members of Parliament during their careers.

THE EARLY VICTORIANS (1839–55)

One of the most notable controversies expounded in the early days of The Spectator magazine occurred when it included a hostile review of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. In 1853 the magazine held the popular author in contempt; the anonymous contributor commenting that the novel ‘would be a heavy book to read through at once … But we … found it dull and wearisome as a serial’2. This observation highlighted the unusual method by which the novels of Charles Dickens reached the general public at the time. The journals that serialised most of his works, such as Bentley’s Miscellany (Oliver Twist), Master Humphrey’s Clock (The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge) and Household Words (Hard Times) are long forgotten. In the mi...