![]()

1

THE IMPORTANCE OF PROFESSIONAL COLLABORATION

“Are we done yet?” This is a common refrain from teachers who feel forced into teacher team meetings that feel artificial or in which precious time is wasted. When we think about collaboration in the workplace, many of us can draw upon negative instances of when it didn’t work. Anecdotes of collaboration time being used to tell “war stories,” unstructured time without a clear purpose or agenda, and personality conflicts overtaking shared learning are all too familiar. If we have been fortunate enough, we can also recall deep and enriching joint work that led to purposeful growth and learning. Instead of minutes crawling by, time flies with engrossing discussions and collaborative practice, both of which have relevance to instructional decision-making and student learning.

Every teacher in every school deserves the opportunity to engage in professional collaboration aimed toward bolder and deeper learning for school improvement. This is not about finding ways to get teachers to “buy in” to so-called professional learning communities that embody none of the terms in the phrase (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008). Often, they are not professional, nor are they learning opportunities, nor are they characterized by community. In part, this is because school improvement efforts and policies have framed teacher collaboration in technical-rational terms, ignoring the ways in which teachers feel either compelled toward or repelled by joint work. Many districts and schools have established teacher collaboration opportunities in order to support changes in teaching and learning, but these collaborative experiences often do not meet their intended goal. Although some teachers have transformative experiences by collaborating with others, a large number do not. And when positive instances of collaboration exist, they may not last.

In this introductory chapter, we establish why professional collaboration is critical at this time, more thoroughly explore what it is, and discuss how it can make a difference. Building on research and practice, we share the ways in which teachers are moved toward joint work because of the motivation, inspiration, and energy that they personally—and collectively—gain from collaborating to improve student learning. We explore how collaborative settings can provide a space for working through the inevitable challenges that accompany the changing nature of teaching in the midst of various forms of accountability across the globe. Collaboration can also be a vehicle for teachers to negotiate complex environments with shifting policies, changing student populations, and new social and political realities beyond the school. Professional collaboration can be transformational in schools if it is oriented toward equity and excellence, thoughtfully engages evidence on student learning, is embedded into day-to-day schooling practices, and is carefully sustained. Ultimately, moving toward bolder and deeper learning for school improvement is built upon harnessing the power of teachers to work together for equitable and excellent schools.

Professional Collaboration as a Key Reform Lever

In the past two decades, collaboration has been viewed as a critical lever for school improvement. Teacher collaboration, especially, is increasingly viewed as an essential ingredient for improving teaching and learning around the world (Harris, Jones, & Huffman, 2017). One longstanding assumption about its impact is that any activity that reduces teacher isolation will be beneficial, in part because it improves teacher morale (Little, 1990). Moreover, professional collaboration is predicated on the belief that teaching is a profession and that teachers have expertise, skills, and knowledge to drive their own professional learning and development (Campbell, Lieberman, & Yashkina, 2017). In theory, there would be equal emphasis on professional and collaboration in these efforts, with careful attention paid to the quality of collaboration that teachers are experiencing and the actual impact on students and school improvement. Actual practice varies, however. The press for teacher collaboration takes place in specific times and places, and implementation has evolved as educators have responded to broader accountability policies and public pressures to improve student achievement.

Although we talk about it as a monolithic entity, collaboration takes different forms in different countries, in large part due to differing perceptions of its value and the time allocated to it (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018; Jensen, Sonneman, Roberts-Hull, & Hunter, 2016; Kelchtermans, 2006). In contrast to the United States, where teachers average 27 hours of teaching per week, teachers in other systems spend anywhere from 10 to 23 hours per week on teaching, leaving more time for professional learning and development (Jensen et al., 2016). Collaboration activities have also been shaped by national and state accountability systems that have defined what school improvement goals are to be prioritized. In the United States, for example, policies driven by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 focused on increasing student achievement in math and English language arts, and critics believe that they led to a narrowing of the curriculum. This narrowing, not surprisingly, had implications for how schools structured their collaboration and, within these spaces, what counted as important data for continuous improvement. Furthermore, federal accountability policies focused on incentives, sanctions, and mandates, and this meant that schools faced high-stakes pressure to improve performance. Many schools and districts in the United States implemented professional learning communities (PLCs) to enable teachers to examine data on student achievement and to chart plans of action collectively.

In other countries, collaboration has taken different forms and served different purposes, often connected to national or local reform agendas. Just as in the United States, many countries expect that teachers will draw on evidence to improve teaching and learning (Stoll, Brown, Spence-Thomas, & Taylor, 2017). In Scotland, efforts to close the achievement gap have involved collaborative teacher action within and between schools (Chapman, Chestnutt, Friel, Hall, & Lowden, 2017). New Zealand is also promoting cross-school collaboration and has focused inquiry among teachers and leaders (Timperley, Ell, & LeFevre, 2017). In British Columbia and in England, networking teachers for inquiry has been integral to systemic educational reform efforts (Kaser & Halbert, 2017). Singapore has implemented professional learning communities as part of a systemwide and state-led initiative (Hairon & Goh, 2017). Ontario, Canada, has supported teacher collaboration systemically as well, but with more of a ground-up approach to incentivize teacher-led professional learning (Campbell et al., 2017).

As school improvement and accountability mechanisms evolve across the globe, how educators are able to practice professional collaboration is also shifting. In their book Collaborative Professionalism, Andy Hargreaves and Michael O’Connor (2018) talked about how the idea has evolved from Shirley Hord’s (1997) conceptualization of professional collaboration for continuous inquiry, to DuFour’s (2004) notion of PLCs, which emphasized teacher teams centered on student achievement, to its current iteration that broadens what counts as learning and collaboration as professional practice across the globe.

Hargreaves and O’Connor (2018) noted that the current generation of professional collaboration reflects five shifts in what is emphasized within collaborative practice:

- From focusing on narrow learning and achievement to embracing wider purposes of learning and human development.

- From being confined to episodic meetings in specific times and places to becoming embedded into teachers’ and administrators’ everyday work practices.

- From being imposed and managed by administrators and their purposes to being run by teachers in relation to issues identified by themselves.

- From serving the purpose of accountability to serving the needs of students.

- From “comfortable” cultures to constraining structures and then to integrated structures and cultures that promote challenging yet respectful conversations about improvement.

(p. 101)

On the whole, these broader shifts represent an expansion of what counts as learning for both students and adults, driven by student needs that are holistically rather than narrowly defined. These shifts also reflect the understanding that to truly use professional collaboration as a lever for educational improvement, individual and collective learning must be integrated with practice as a day-to-day feature instead of ad-hoc or in weekly set-aside meetings.

In their study of professional learning in four high-performing systems (British Columbia, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Singapore), Jensen et al. (2016) noted that “collaborative professional learning is built into the daily lives of teachers and schools leaders” (p. 4). More importantly, every educator is responsible for not only their own learning but also the learning of their colleagues. Collective learning and capacity building are emphasized. This is reinforced by reviews of international research, which suggest that effective PLCs exhibit key characteristics such as shared values and vision, collective responsibility, reflective professional inquiry, and collaboration (Kelchtermans, 2006; Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006; Vangrieken, Dochy, Raes, & Kyndt, 2015; Vescio et al., 2008).

There is also some evidence suggesting that professional collaboration, especially among teachers, can support positive student achievement (Goodard et al., 2010, cited in Ronfeldt, Farmer, McQueen, & Grissom, 2015; Saunders, Goldenberg, & Gallimore, 2009). Ronfeldt and colleagues (2015) found that “Teachers and schools that engage in better quality collaboration have better achievement gains in math and reading” (p. 475). In addition, the researchers concluded that quality professional collaboration can also lead to teacher learning and improvement: “Teachers improve at greater rates when they work in schools with better collaboration quality” (p. 475).

Several reviews of research on professional collaboration make it clear that not all collaborative practices are created equal, however. Studies examining qualities of teacher collaboration suggest that focusing on curriculum, instructional decision-making, and analysis of student data are more likely to promote student achievement gains (Ronfeldt et al., 2015; Vescio et al., 2008). Additionally, when there is frequent collaboration that is structured around inquiry protocols and student data and led by trained instructional leaders, teams are more likely to support improvements in student learning (Gallimore, Ermeling, Saunders, & Goldenberg, 2009; Saunders et al., 2009).

The Role of Data Use in Professional Collaboration

As practice and research continue to delve into how professional collaboration can support school improvement, teacher development, and student learning, data inquiry has become a necessary tool for understanding student learning needs and informing cycles of continuous improvement (Datnow & Park, 2014). Just like any tool for educational improvement, the use of data is constructed within a larger structure and culture and made sense of by individuals and groups that take part in professional collaboration. The literature on data use in schools offers a clear delineation between high-stakes, accountability-driven data use, which emphasizes complying with external pressures and bureaucratic demands, and data use for continuous organizational learning and improvement.

Firestone and González (2007) explained that an accountability-driven culture focuses on student test scores, tends to have a short-term time frame, and excludes teacher and principal voices. Data are used mainly to identify problems and monitor compliance. In contrast, they noted, data use for continuous improvement focuses on student and organizational learning and instructional improvement, is long-term in scope, and includes teacher and principal voices. Data are used to identify and diagnose problems. Educators who are focused on continuous improvement actively seek out a wide range of data and do not limit themselves to data linked to accountability mechanisms. The limitations of benchmark assessment data and teachers’ interest in creating a more complete portrait of student achievement leads teachers to draw on a wide range of data to inform instructional decisions. The sources of data that teachers actually rely upon go well beyond these measures and include teacher-created assessments, curriculum-embedded assessments, writing portfolios, results from student work with online instructional tools, and of course their own observations of student learning.

When data are used during professional collaboration to foster inquiry, to critically examine instructional practices, and to identify opportunities to learn for both students and teachers, the information can be a useful tool for reflection and improvement (Horn & Little, 2010; Huguet, Farrell, & Marsh, 2017; Nelson, Slavit, & Deuel, 2012; Park, 2018; Schildkamp, Poortman, & Handelzalts, 2016). At the intersection of professional collaboration and data use, however, lies a black box with regard to how these practices actually unfold, evolve, and are enacted by teachers. We need a greater understanding of how teachers engage in professional collaboration with data use, taking into consideration not only the technical and procedural aspects of these practices but also the cultures in which they take place, the emotions they evoke, or the ways in which educators make sense of them. We have very few studies that “zoom in” on teacher practice (Little, 2012), and thus, despite the attention to data-driven decision-making in K–12 educational reform and policy, we know little about what teacher collaboration looks like in practice, especially with respect to the use of data. As such, key questions remain: What conditions support professional collaboration? And what role should data—or information on student learning more broadly—play in professional collaboration? This book helps to answer these questions and fill these gaps in our understanding.

Our Framework and Approach

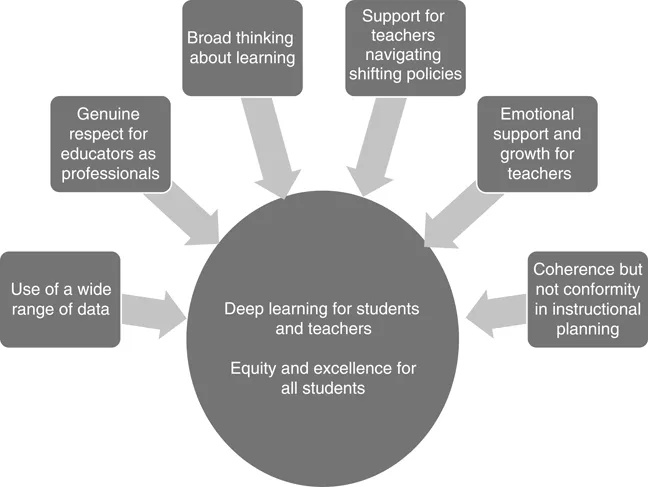

Figure 1.1 Purposeful Professional Collaboration: A Framework for Teacher Learning in Equitable and Excellent Schools

In this book, we use in-depth empirical data to conceptualize professional collaboration. As described in Figure 1.1, to be purposeful, these efforts must embody a range of key qualities, from a focus on equity and excellence to respect and support for teachers as professionals and human beings.

We situate our work with the work of other scholars who believe in the potential of teacher joint work to foster meaningful improvements in teaching, learning, and equity. We adhere to a model of professional collaborative practice where both the notions of teacher professionalism and collaboration are equally emphasized. Borrowing from Hargreaves and O’Connor (2018), we define the professional aspect of professional collaboration as

exercising good judgment, being committed to improvement, sharing and deepening expertise, and getting neither too close to nor too distant from the people the profession serves. The collaborative aspect of professionalism refers to how members of their profession labor or work rather than merely talk and reflect together.

(p. 4)

We believe that talking and reflection are important aspects of collaborative learning, but this must be coupled with actions that directly lead to improving student learning and equitable outcomes. Furthermore, professional collaboration needs to be sustainable and not contribute to teacher burnout or lead to the deprofessionalization of teachers (Apple, 1986; Kelchtermans, 2006). Reforms aimed at co...