eBook - ePub

A Smith in Lindsey

The Anglo-Saxon Grave at Tattershall Thorpe, Lincolnshire

- 123 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Contents Include: An introduction to the grave, conservation, metallurgical and other analyses, a catalogue of organic and inorganic materials, and a discussion of dates and context."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Smith in Lindsey by David A. Hinton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Acknowledgements

As I did not work on the excavation which produced the material catalogued in this report, I cannot personally thank the individual diggers who rescued it, but I am grateful to Naomi Field for her help in describing to me the difficulties under which they worked. Peter Chowne introduced me to the material, and gave me access to the archive of the excavation.

Many of those to whom I owe thanks are contributors to this volume. A number of other people have commented on the material from time to time, however, and their help is not all individually acknowledged. Many of them attended a symposium held in Salisbury in 1989. In particular, Leslie Webster of the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, British Museum, who was the first early medieval specialist to inspect the material, has been a source of advice and encouragement.

English Heritage has made grants available both for conservation of the material and for the publication of this report, and I am grateful to Helen Keeley and Christopher Scull for monitoring the work and advising about it; by happy coincidence, the latter is also a contributor. Several members of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory have been involved directly or indirectly; as well as those named in or contributors to the text, I should like to thank Michael Corfield and Justine Bayley for making the work possible.

Many people have worked on the material while it has been undergoing conservation in Lincoln, initially under the aegis of Kate Foley and then of Robert White; principal among them have been Fiona Macalister, Claire Dean, Rebecca Allman and Michelle Le Marie.

The drawings were done in Lincoln by Dave Watt, formerly illustrator at the City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit. The photographs were taken by Robert White and Keith Smith in the Lincoln Conservation Department.

The text has benefited greatly from comments by Professor John Hines, of the University of Wales, Cardiff, both as a specialist in Anglo-Saxon studies and as Honorary Edior of the Society for Medieval Archaeology; all have been incorporated, albeit mostly sotto voce.

Chapter One

Discovery and Investigation

Introduction

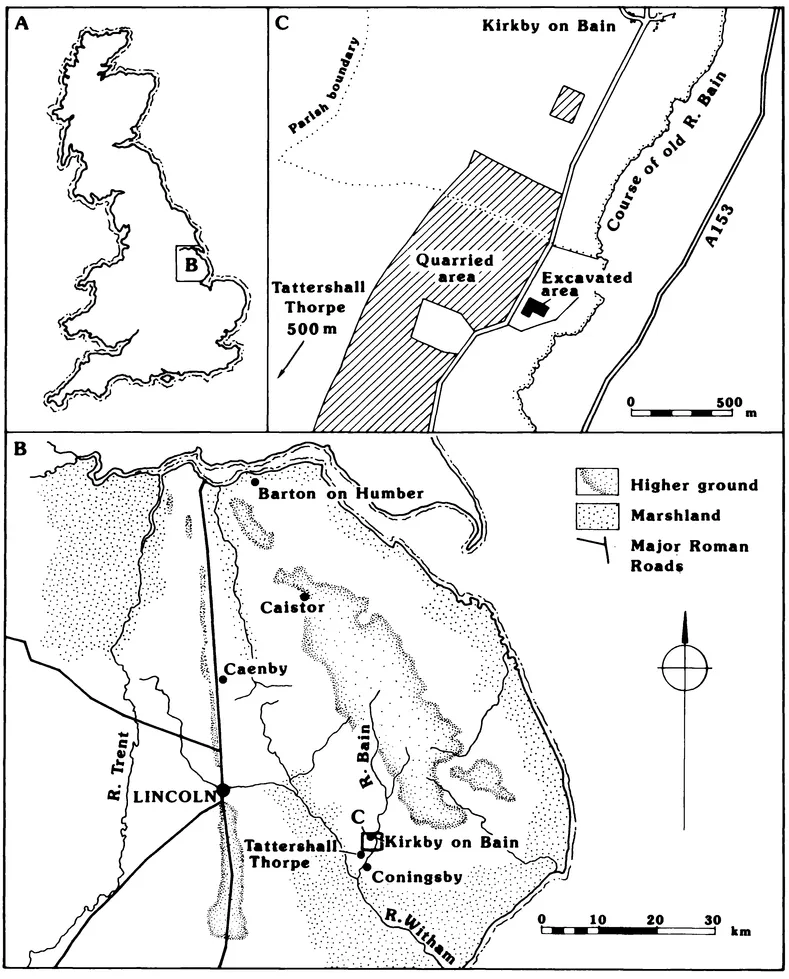

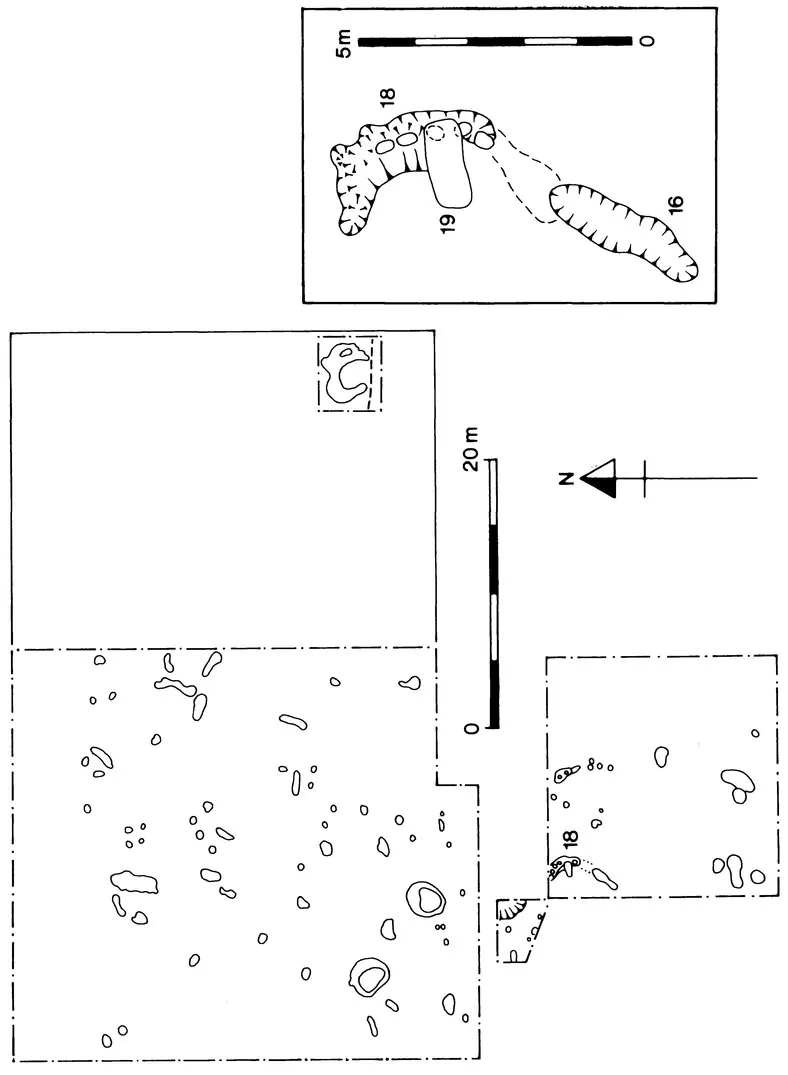

The unique early medieval assemblage of tools, other objects and fragments of metal and glass described in this monograph was discovered in February 1981 during excavations directed by Mr (now Dr) Peter Chowne, then of the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology, in advance of gravel digging in the flood-plain of the River Bain at Tattershall Thorpe, Lincolnshire (Fig. 1; National Grid Reference TF 238608). Prehistoric material, of various dates, and three Roman pits were found on the site, but the only later features were a medieval ditch and a single, sub-rectangular feature, 19, which contained the assemblage (Fiars. 2 and 3).1

There was no reason to think that Feature 19 would be complicated to excavate, but it proved to contain a large quantity of artefacts, many of which had corroded together. Because they might have been damaged by attempting to separate them in the ground, and because of the risk of their clandestine removal if left overnight, it was decided to lift as much as possible out en bloc, so that further work could be undertaken in Lincoln at the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology's Conservation laboratory. At first it was thought that the material was Roman, because of the coins that were observed, and the original site drawings are labelled 'Roman disturbance'. Only after post-excavation work began was it realised that some of the material had to be Anglo-Saxon in date.

Preliminary separation and conservation work was done in the laboratory, and the importance of the material became apparent on recognition that it comprised a number of craft tools as well as a selection of other items and scrap implying a smith's working hoard. In 1982, further advice was sought, notably from Mrs Leslie Webster of the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, British Museum, whose notes have been invaluable in the writing of this report, and from various members of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission (England), now English Heritage; their work is included in the relevant sections of the 'Catalogue' and 'Discussion'. Progress was made on the conservation, but post-excavation was not complete at the time that the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology was wound up, and in 1989 Dr Chowne, having joined the Trust for Wessex Archaeology, asked the writer if he would be interested in seeing the material.

FIG. I

Tattershall Thorpe: Site location

Tattershall Thorpe: Site location

FIG. 2

Tattershall Thorpe: Site plan

Tattershall Thorpe: Site plan

FIG. 3

Tattershall Thorpe: Feature 19 after excavation, from the north-east. The circle and post-holes are Neolithic, with the rectangular early medieval grave cutting it. Burrowing animals had caused considerable disturbance From a colour slide by N. Hawley

Tattershall Thorpe: Feature 19 after excavation, from the north-east. The circle and post-holes are Neolithic, with the rectangular early medieval grave cutting it. Burrowing animals had caused considerable disturbance From a colour slide by N. Hawley

To demonstrate the importance of the collection, a small symposium was held in Salisbury in 1989, as a consequence of which an interim report was published.2 English Heritage kindly agreed to fund further work on conservation and analysis, coordinated by and largely undertaken at the Lincoln City and County Museum Laboratory (the successor to the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology's laboratory), and subsequently to support publication of this volume. Preparation of the report became the writer's sole responsibility when Dr Chowne became Head of the Museum of London Archaeological Service in 1991.

The gravel pit was owned by Bain Aggregates at the time of the excavation; the objects passed from that company into the ownership of the Woodhall Spa Sand and Gravel Company, which generously donated them to the Lincoln City and County Museum in 1995.

The Grave

The Site Record Sheet for Feature 19 records it as immediately underlying the topsoil and cutting Features 3 and 18, the latter a Neolithic foundation trench, the former perhaps just a tree-root hole (Fig. 2). The subsoil was a patch of clay within the gravel. The feature was 1.72 m long by 0.70 m wide, and up to 0.40 m deep, with a fill of sand and small stones, and 'Remains of skeleton, bronze, iron, glass, R-B coins'. About a dozen colour slides were taken during and immediately after excavation (Fig. 3), and a similar number of black-and-white photographs. Drawings consist of outline sections and plans.

Neither the contact prints (the photographic negatives have been mislaid) nor the slides show much detail of objects in situ. None shows traces of a skeleton, but in a letter of 12 March 1981 to Mr Glyn Coppack, then Inspector of Ancient Monuments for Lincolnshire, Ms Naomi Field, then of the Trust for Lincolnshire Archaeology, described 'an inhumation . . . most of the bones had diss...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Summary/Sommaire/Zusammenfassung

- Concordances

- Index