![]()

1

WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY AND REASONING

Nash Unsworth

A great deal of research has demonstrated an important link between working memory capacity and reasoning (e.g., Kyllonen & Christal, 1990; Engle et al., 1999; Kane et al., 2004). Despite the large amount of evidence for this relation, the reasons for it remain unclear. In the current chapter, this link is examined primarily from an individual differences perspective, focusing on which working memory components are thought to be important for reasoning. A brief overview of working memory and individual differences in working memory capacity will be given, followed by an examination of several approaches that have been used to better understand the role of working memory in various aspects of reasoning.

Individual differences in working memory capacity

Before discussing the relationship between working memory capacity and reasoning, we will briefly describe working memory capacity, how it is measured, and review the importance of it in predicting performance on both higher-order and lower-order cognitive tasks. Working memory is considered to be a system responsible for active maintenance and on-line manipulation of information over short intervals. In our view, working memory consists of a subset of activated traces above threshold, some of which are highly active strategies for maintaining activation of those traces, and an attention component (e.g., Engle et al., 1999). Thus, our view of working memory emphasizes the interaction of attention and memory in the service of complex cognition. In order to measure the capacity of working memory, researchers have relied on complex working memory span tasks based on the working memory model of Baddeley and Hitch (1974). Beginning with Daneman and Carpenter (1980), these tasks combine a simple memory span task with a secondary processing component. Initially, the idea was that these tasks would better measure a dynamic working memory system that traded off processing and storage resources. Thus, in these tasks participants are required to engage in some form of processing activity while trying to remember a set of to-be-remembered (TBR) items. As an example of such a task, consider the operation span task that requires participants to solve math operations while trying to remember unrelated words in the correct serial order (Turner & Engle, 1989). Several variations exist of this basic paradigm, with most variations consisting of different processing tasks or differences in stimuli.

Despite all these variations, performance on these complex span tasks has been shown to co-vary with performance on a number of both higher-order and lower-order cognitive tasks. Indeed, the original work of Daneman and Carpenter (1980) demonstrated that performance on complex span tasks was highly related to reading comprehension performance as measured by the verbal portion of the SATs. These complex span tasks are also related to other higher-order processes including vocabulary learning (Daneman & Green, 1986), complex learning (Kyllonen & Stephens, 1990), as well as fluid reasoning (Engle, et al., 1999; Kane et al., 2004). This impressive list demonstrates the predictive utility of working memory capacity (WMC) in a number of research domains.

Additional work has shown that WMC is also implicated in performance on many lower-order attentional tasks. This work has demonstrated that individuals who perform well on measures of WMC tend to perform better on basic attention tasks in a variety of conditions. This includes performance on tasks such as Stroop, antisaccade, dichotic listening, and flankers (see Kane et al., 2007; Unsworth & Spillers, 2010, for reviews). Clearly, then, WMC is an important predictor of behavior in a number of different situations.

Based on this prior work we have developed a theory of individual differences in WMC which suggests that these result from multiple components, each of which is important for performance on a variety of tasks (Unsworth & Engle, 2007a; Unsworth & Spillers, 2010). In particular, in our work we have suggested that both attention-control abilities and controlled search from secondary memory are important. In this framework, the attentional component serves to actively maintain a few distinct representations for on-line processing in primary memory. These representations include things such as goal states for the current task, action plans, partial solutions to reasoning problems, and item representations in listmemory tasks. In this view, as long as attention is allocated to these representations, they will be actively maintained in primary memory (Craik & Levy, 1976). This continued allocation of attention serves to protect these representations from interfering internal and external distraction, similar to the attention-control view espoused by Engle and Kane (2004). However, if attention is removed from the representations, due to internal or external distraction or to the processing of incoming information, these representations will no longer be actively maintained in primary memory, and therefore will have to be retrieved from secondary memory if needed. Accordingly, secondary memory relies on a cue-dependent search mechanism to retrieve items (Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981). Additionally, the extent to which items can be retrieved from secondary memory will be dependent on overall encoding abilities, the ability to reinstate the encoding context at retrieval, and the ability to focus the search on target items and exclude interfering items (i.e., proactive interference). Similar to Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968), this framework suggests that working memory is not only a state of activation, but also represents the set of control processes that are needed to maintain that state of activation, to prevent other items from gaining access to this state of activation, and to bring other items into this state of activation via controlled retrieval (Engle et al., 1999). Thus, individual differences in WMC are indexed by both attention-control differences and retrieval differences. Furthermore, we have also suggested that other components are important (Unsworth & Spillers, 2010). These other components include the maximal number of items that can be held in primary memory (or the focus of attention; Cowan, 2001), the ability to rapidly update the contents of working memory and switch items in and out of the primary memory (Oberauer, 2002; Unsworth & Engle, 2008), as well as binding operations that are needed to momentarily bind items (Halford, Cowan, & Andrews, 2007; Oberauer, 2005; see Halford, Andrews, & Wilson in this volume). As will be seen below, a number of components are likely important for reasoning, and likely why WMC and reasoning tend to be so strongly correlated.

Working memory capacity and reasoning

Beginning with the work of Kyllonen and Christal (1990), research has suggested that there is a strong link between individual differences in WMC and reasoning abilities. In particular, this work suggests that at an individual task level, measures of WMC correlate with reasoning measures around .45 (Ackerman, Beier, & Boyle, 2005) and at the latent level, WMC and reasoning are correlated around .72 (Kane, Hambrick, & Conway, 2005). Thus, at a latent level WMC and reasoning seem to share approximately half of their variance. This suggests that there are clearly important links between WMC and reasoning, but also that these two constructs are not isomorphic. Note, for the most part prior research has focused more on inductive reasoning tasks, rather than on deductive reasoning tasks. However, recent work by Wilhelm (2005) suggests that inductive and deductive reasoning are perfectly correlated, and thus load on the same general reasoning factor. Wilhelm (2005) further pointed out that reasoning measures could be delineated based on their content (verbal, numerical, spatial). Given that prior research has primarily focused on inductive reasoning and the fact that inductive and deductive reasoning abilities seem to be strongly correlated, the current chapter will primarily focus on the link between WMC and inductive reasoning abilities. Furthermore, note that in the current chapter we will focus on inductive reasoning measures used primarily in the intelligence literature, rather than other types of inductive reasoning measures. See Feeney, Hayes, and Heit (this volume) for a discussion of the relation between recognition memory and these other inductive reasoning measures.

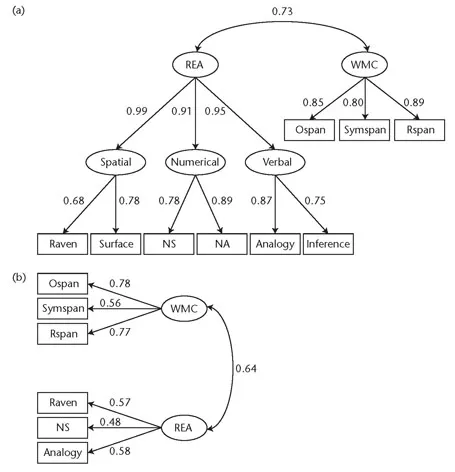

As an example that WMC is strongly correlated with general reasoning, we reanalyzed data from a prior study (Unsworth et al., 2009) that examined the correlation between WMC and multiple measures of reasoning. Important for the current discussion is the fact that in this study we used three WMC measures, each of which differed in its content, as well as six reasoning tasks that also varied in their content. Shown in Figure 1.1a is the resulting latent variable model. As can be seen, there was a higher-order reasoning factor composed of lower-order content-specific reasoning factors, each of which loaded strongly on the higher-order factor. Importantly, this reasoning factor was strongly correlated with the WMC factor. Thus, consistent with much prior research, WMC and reasoning (broadly defined) were strongly related. As a further example of this relation, we reanalyzed data from 630 participants from our laboratory, each of whom had completed three WMC measures and three reasoning measures. Shown in Figure 1.1b is the resulting latent variable model. As can be seen, WMC and reasoning abilities again were strongly related. These examples demonstrate that WMC and reasoning are strongly related and share a good deal of common variance. Furthermore, these examples demonstrate that this important relation is domain-general in nature, given that both the WMC and reasoning factors were made up by tasks varying in their content. This suggests that whatever the reasons for the relation between WMC and reasoning abilities, they are likely domain-general and cut across multiple different types of tasks.

Not only is it important to demonstrate that WMC and reasoning are related at the latent level, it is also important to demonstrate that similar relations are found at the individual task level, and to explore these task-level relations in more detail. For example, in our sample of 630 participants, the correlation between WMC and the Raven Advanced Progressive Matrices was .40. Likewise, the correlation between WMC and number series was .32, and the correlation between WMC and verbal analogies was .35. These values correspond well with the overall meta-analytic correlation reported by Ackerman et al. (2005), and suggest that the correlation between WMC and reasoning is remarkably similar for different types of reasoning tasks. Thus, it is not simply the case that WMC correlates only with matrix reasoning tasks, or only with analogical reasoning tasks, but rather that WMC seems to be related to various different types of reasoning tasks that vary not only in the type of reasoning required, but also in the content.

Further examination of these task-level correlations is important to rule out various explanations for the correlation between WMC and reasoning. For example, one common explanation for the relation between WMC and measures of reasoning is based on item difficulty, such that on the easiest reasoning problems WMC will not be taxed much, allowing for even low-WMC individuals to get the correct answer. However, as difficulty increases due to an increase in the number of rules or goals that have to be maintained, WMC will be taxed more, allowing only the high-WMC individuals to generate the correct answer (Carpenter, Just, & Shell, 1990). According to these types of views, the correlation between WMC and reasoning should be small to nonexistent on the easiest problems, but the correlation should steadily increase as difficulty increases. Given that many reasoning tasks are structured such that the easiest problems are at the beginning and the hardest problems are at the end, these views predict that the correlation between WMC and solution accuracy should increase as a function of problem number. However, prior work has found no such relation. In fact, prior work suggests a nearly flat relation across difficulty levels (Salthouse, 1993; Unsworth & Engle, 2005; Wiley et al., 2011). One limitation for these prior studies is that they typically only focused on one WMC measure and one reasoning measure (Ravens). Therefore, to examine the notion that item difficulty drives the correlation between WMC and reasoning, we examined the item correlations for the Ravens, number series, and verbal analogies with the composite WMC variable described previously. As shown in Figure 1.2a, the correlations between solution accuracy for each Raven item and WMC, although fluctuating widely, do not appear to increase in any systematic manner as difficulty increases.1 Indeed, the correlation between WMC and accuracy on the first problem was as high as with the last problem. These results replicate prior research that has specifically focused on the Ravens. Perhaps more interestingly, similar patterns emerged on both the number series (Figure 1.2b) and the verbal analogies (Figure 1.2c) tasks. In all cases there does not seem to be a systematic relation between WMC and solution accuracy as a function of item number.

FIGURE 1.1 (a) Confirmatory factor analysis for higher-order reasoning factor (REA) based on lower-order factors composed of spatial, numerical, and verbal reas...