eBook - ePub

Life-span Developmental Psychology

Introduction To Research Methods

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Life-span Developmental Psychology

Introduction To Research Methods

About this book

What are the changes we see over the life-span? How can we explain them? And how do we account for individual differences? This volume continues to examine these questions and to report advances in empirical research within life-span development increasing its interdisciplinary nature. The relationships between individual development, social context, and historical change are salient issues discussed in this volume, as are nonnormative and atypical events contributing to life-span change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life-span Developmental Psychology by Paul B. Baltes,Hayne W. Reese,John R. Nesselroade in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Field of Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology deals with behavioral changes within persons across the life span, and with differences between and similarities among persons in the nature of these changes. Its aim, however, is not only to describe these intraindividual changes and interindividual differences but also to explain how they come about and to find ways to modify them in an optimum way. In addition, developmental psychology recognizes that the individual is changing in a changing world, and that this changing context of development can affect the nature of individual change. Consequently, developmental psychology also deals with changes within and among biocultural ecologies and with the relationships of these changes to changes within and among individuals.

Chapter One

Why Developmental Psychology?

A Rationale for Developmental Sciences

What are the advantages to organizing and building knowledge about behavior around the concept of developmental psychology? The case for a developmental approach to the study of behavior is similar to the arguments developed in other sciences for using:

knowledge about sociocultural history to better understand present political events;

knowledge about paleontology to understand the nature of current world geography;

knowledge about the length and frequency (life history) of cigarette smoking to predict the probability of adult lung cancer;

knowledge about past stock market trends to predict next year’s stock market situation and the value of a given portfolio;

knowledge from archaeology to develop a fuller understanding of modern civilization; and

knowledge about the summer climate in California to predict the quality and taste of California’s fall wines.

The developmental psychologist, in a parallel fashion, is interested in questions centering around the description, explanation, and modification of processes that lead to a given outcome or sequence of outcomes. Examples of questions about the description, explanation, and modification of processes and outcomes are:

Is cognitive behavior the same in various age groups, or does it change from infancy through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood?

If there are stages of cognitive functioning, why do they follow one another, and what mechanism explains the transition from one stage to another?

Are there sex differences in adult personality traits, and, if so, how do they come about?

Is schizophrenia in adulthood related to early life experiences, or does it develop instantaneously due to stress in adulthood?

What are the tasks that characterize adult development (for example, marriage, parenthood)? Is successful mastery of these tasks related to early life experiences, and how can a given life history be designed to maximize adult functioning?

How and when is achievement motivation formed? To what aspects of parenting behavior does it relate, and what do parents have to do in order to increase achievement motivation in their children?

In all of these examples, both from other developmental sciences and from developmental psychology, there are two primary characteristics: a focus on change and the study of processes leading to a specific outcome. Specifically, the sample questions presented suggest:

1. The phenomenon under study by a developmental scientist is not fixed and stable but subject to continuous and systematic change that needs description.

2. Because phenomena come about not instantaneously but as a result of processes, it is useful to know something about the present and the past when explaining the nature of a phenomenon, predicting its future status, and designing a context for optimization or modification.

Phenomena, then, are not fixed; they are changing. Furthermore, both the past and the present are a prologue to the future. Most scientists have acknowledged the usefulness of such a “historical,” process-oriented developmental approach to the study of their subject matter. It is worthwhile to think a bit about other sciences that focus on change and time-related phenomena (history, archaeology, astronomy, and others).

All time- and history-oriented sciences share with developmental psychology a number of rationales and complexities of methodology. For example, when attempting to understand why some adult persons are extroverts and others introverts, a developmental psychologist may design a methodology to “retrospect” into the past in order to find key antecedents to the emergence of extroversion/introversion behavior. Such retrospective methodologies are not easily developed and validated. In our rapidly changing world, it is often possible only to approximate ideal methods, using so-called quasi-experimental (Campbell & Stanley, 1963, 1966) methodology. The same methodological complexity is confronted by the astronomer, the archaeologist, or the political historian, in at least equally dramatic fashion.

As will be seen later, it is occasionally desirable for the developmental psychologist to look to other “historical” disciplines for ideas about adequate research methodologies, since these disciplines are often more advanced. The development of sequential cross-sectional or longitudinal strategies, for example (see Chapter Fourteen), has a precursor in demography that goes back to the 18th century. Similarly, the term development has been widely discussed in the biological sciences, and the biologist’s view of development has strongly influenced the meaning of this term in the behavioral sciences. As another example, the recently suggested use of path-analysis techniques (see Chapter Twenty-Four) as a way of testing hypotheses about long-term developmental chains has its roots in other “historical” disciplines such as epidemiology and sociology.

Describing, Explaining, and Optimizing Development

Before the methods of developmental psychology are described, the task of developmental research will be outlined. This exercise is aimed at helping the reader to focus on the questions developmental psychologists typically ask (Baltes, 1973).

Definitions of a concept or a discipline always reflect personal biases, and most researchers are somewhat reluctant to freeze a theoretical idea or orientation by specifically defining it. For the present purpose, a definition of developmental psychology is proposed that is methodology-oriented and that views developmental psychology less as an independent body of knowledge than as an orientation toward the way behavior is studied:

Developmental psychology deals with the description, explanation, and modification (optimization) of intraindividual change in behavior across the life span, and with interindividual differences (and similarities) in intraindividual change.

Intra individual change is within-individual change; inter individual differences are between-individual differences. The focus of a developmental approach, then, is on examining within-person (intraindividual) variability or change and the extent to which such variability is not identical for all individuals. If intraindividual change is not identical for all individuals, it shows between-person (interindividual) differences. Although these terms may appear clumsy and confusing, their widespread use by behavioral scientists interested in methodology makes it desirable to include them here as key concepts.

The task of a developmental approach, however, does not stop with naturalistic description of the course of change. The aims of developmental psychology include the pursuit of knowledge about the determinants and mechanisms that help us understand the how and why of development: what causes the change? This aspect of knowledge-building is often called explicative, explanatory, or analytic, because its goal is to find causal-type relationships and thus to go beyond descriptive predictions of the nature of behavioral development. The decision as to where description ends, when explanation starts, and which form of explanation is acceptable to a given scientist will always be an arbitrary one. As a matter of fact, philosophers of science question the logical merit of such a distinction on the grounds that description and explanation go hand in hand and are intrinsically confounded. For didactic purposes, however, the distinction is useful because it helps us present a perspective on research strategies and particular emphases in theory-building.

The proposed definition of developmental psychology further states that developmental psychologists are interested not only in description and explication but also in modification and optimization of the course of development. This task requires that we discover which interventions or treatments are powerful change agents. A useful benefit of this aim is that knowledge that may be generated for its own sake may, by its application, serve society in its attempts to design an optimal context for living.

The simultaneous knowledge of what behavioral development looks like (description), where it comes from and why it comes about (explanation), and how it can be altered (modification) makes for a full-fledged body of knowledge. Accordingly, useful developmental methodology consists of methods that permit us to describe intraindividual (within-person) change sequences and interindividual (between-person) differences in these patterns of change, as well as assist us in our search for explanatory and modification principles.

Developmental psychology is a fairly recent scientific field. Therefore it is understandable that its methodology is often insufficiently formulated or inadequately adapted to the unique features of its basic approach. In fact, to give one example, many of the classic experimental designs (such as analysis of variance) have been developed within the framework of interindividual differences and not intraindividual variability. The best developmental designs, however, are the ones that yield descriptive and explanatory information about intraindividual change patterns.

Summary

A developmental approach, in any science, is based on the belief that knowing the past allows us to understand the present and to predict the future. In psychology, this belief leads to a developmental psychology that deals with the description, explanation, and modification (including optimization) of intraindividual change in behavior across the life span, and with interindividual differences in intraindividual change. For these purposes, methods are needed that permit description of intraindividual change and interindividual differences in the nature of intraindividual change, and that assist in the identification of causal mechanisms (explanation) and modification principles (optimization).

Chapter Two

An Illustration of the Developmental Approach: The Case of Auditory Sensitivity

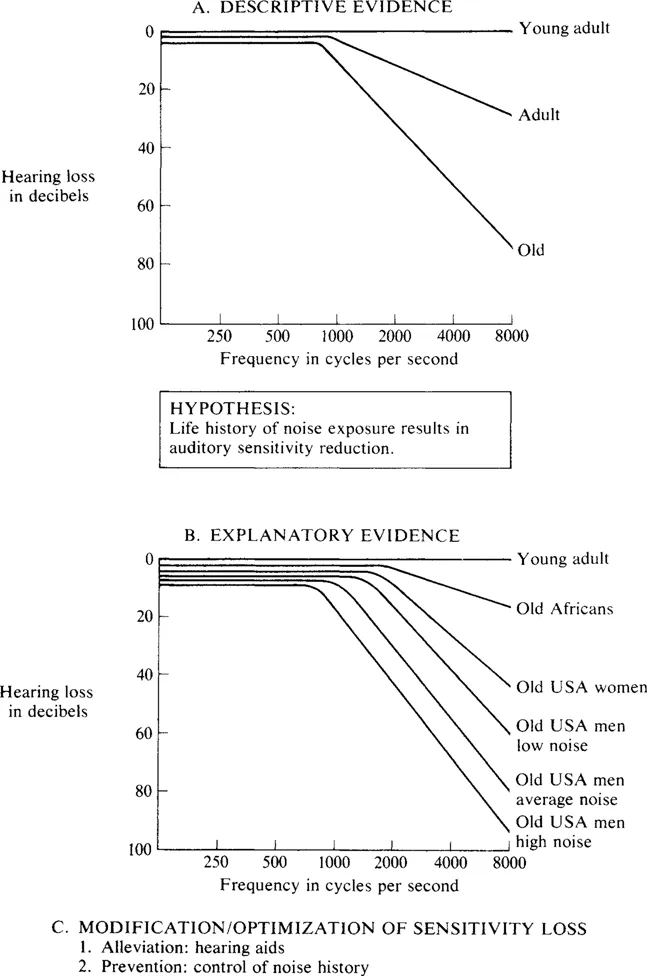

The area of auditory sensitivity provides a good example to illustrate the goals of describing, explaining, and modifying a developmental phenomenon. This area of research has been well summarized by McFarland (1968), using data from a number of studies, including those by Glorig and Rosen and their colleagues. Figure 2-1 illustrates the key arguments.

Description

Auditory sensitivity, or acuity, has been measured in large samples covering a wide age range. When auditory acuity is plotted against pitch of tones, a fairly robust age-difference pattern can be seen. Specifically, Part A of Figure 2-1 shows the loudness (in decibels) required for a particular tone to be detected. In general, it takes more loudness for an older person to hear a particular tone than for a young adult to hear it. The louder a tone has to be in order to be heard, the less is the person’s auditory sensitivity.

There is a definite age-related decrease in sensitivity, especially for the higher pitches (frequencies of 2000 cycles per second and higher); that is, as shown in Part A of the figure, auditory sensitivity seems to exhibit a definite developmental trend in that the loss is neatly correlated with tone pitch or frequency. (For a summary of design questions involving the distinction between age changes and age differences, see Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen.) Thus, auditory sensitivity is not fixed for a given person but changes with time. Moreover, as shown in Part B of the figure, there are interindividual differences in the developmental trends obtained. For example, women tend to show less of a decrement than men.

Figure 2-1. Descriptive and explanatory research on auditory sensitivity in adulthood. Based on data from McFarland (1968).

Explanation

Part A of Figure 2-1 describes average change in hearing acuity in adulthood. A series of studies has been conducted to shed light on the causes of this robust age-related change pattern in auditory sens...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Part One The Field of Developmental Psychology

- Part Two General Issues in Research Methodology

- Part Three Objectives and Issues of Developmental Research in Psychology

- Part Four Descriptive Developmental Designs

- Part Five Explanatory-Analytic Developmental Research

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index