![]()

Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay

DAVID M. ROBINSON AND STUART HARRISON

This article has its origins in a paper on Cistercian cloisters presented by David Robinson at the 2004 Rewley House conference on the medieval cloister in England and Wales. Subsequently, it was felt that a JBAA volume dedicated to cloisters would be deficient were it to ignore the very significant work done by Stuart Harrison in enhancing our understanding of white monk cloisters, and that this was the perfect opportunity to bring together the complementary skills of both authors. The paper comes in two parts, an essay and gazetteer.

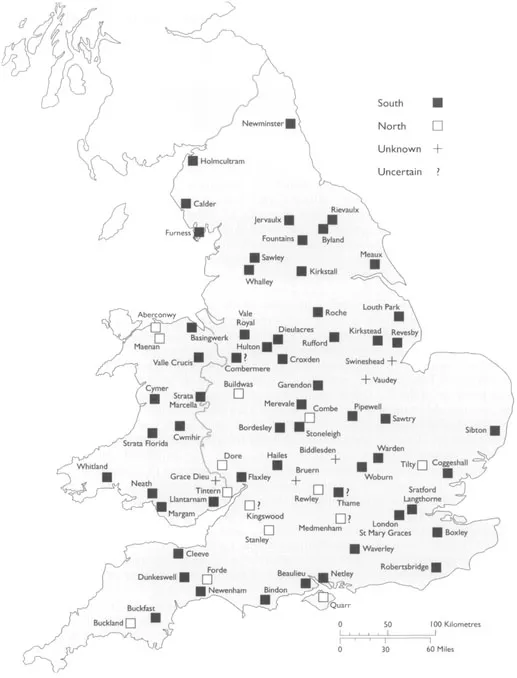

PERHAPS the most powerful expression of the success achieved by the Cistercian order in medieval Europe was the extraordinary proliferation of its houses.1 After two centuries of sustained growth, by the beginning of the 14th century there were more than 700 Cistercian abbeys situated in virtually every corner of the Christian west.2 The total number of foundations in England and Wales eventually stood at about seventy-five (Fig. 1). There were eleven more abbeys in Scotland, and another thirty-five or so in Ireland.3 Given such large numbers, on the face of it there seems to be considerable potential for comparative architectural study over a very wide area. Indeed, this has been a consistent strand running through Cistercian studies for well over a century. Expectations have been heightened by a recognition of the remarkably strong centralised governance of the order, and by the belief that the fierce drive for self-identity within the movement must have encouraged the adoption of a distinct architectural aesthetic. Time and again, however, scholars have warned of reading too much into the veneer of uniformity which is sometimes thought to characterise Cistercian building.4 In particular, we must remember that despite the fullness of the order's early narrative and legislative texts, covering widely disparate facets of 'white monk' life, the content is astonishingly vague on the question of architecture.5 Apart from a single reference to bell towers, there is, as Christopher Holdsworth has pointed out, 'not a word about the size and shape of the buildings in which the monks were to live and pray'.6

With this all-important caveat firmly in mind, the purpose of this paper is to look at one rather neglected aspect of Cistercian architecture, namely the cloister garth.7 We pay particular attention to the surrounding arcades, though other prominent characteristics of the generally four-square open court are also considered. The content focuses very much on the Cistercian cloisters of England and Wales, and to this end is underpinned by the comprehensive gazetteer which follows on from this essay. The paper also presents the opportunity to bring together an important portfolio of English and Welsh arcade reconstructions, a number of them published

FIG. 1. Cistercian abbeys in England and Wales: map to show position of known cloisters Pete Lawrence for Cadw, Welsh Assembly Government

here for the first time. Our horizons are, however, by no means restricted to these shores. On the contrary, for a fuller appreciation of chronological developments, as well as for an understanding of the significance of individual garth features, it is essential we consider something of the wider European Cistercian context.

The essay is arranged in four principal parts. First, there is an introduction to the basic qualities of the Cistercian cloister, concentrating on its physical attributes while keeping an eye on conceptual interpretations of the space. The second and third sections provide a chronological overview of the development of Cistercian cloister arcading in England and Wales, before and after c. 1300. Finally, we consider a number of significant architectural features of the garth, focusing primarily on 'lanes', lavers, collation seats and their associated arcade bays.

Qualities of the Cistercian Cloister

SUCH is the dominance of the cloister (claustrum) in medieval monastic planning that it is easy to take its ubiquity for granted. In many ways, the success of its four-square architectural form — especially in northern climes — remains a puzzle. Walter Horn described it as 'one of the great mysteries of medieval architecture'.8 Nevertheless, the cloister was adopted by virtually every European religious order, almost without question and regardless of any specific ideals. It is rightly seen as the single most inventive and 'enduring achievement' of monastic building.9

With one or two significant modifications to the surrounding buildings, the cloister eventually proved fundamental to Cistercian monastic planning. It was a place, as we shall see, in which important liturgical expressions of the community were enacted. Cut off from the outside world both physically and spiritually, the central open court or garth served as a haven of tranquillity at the heart of the abbey complex.10 On all four sides were passages, usually covered with lean-to roofs, known as cloister walks, galleries, or alleys. Fronted by handsome rhythmic arcades of a generally uniform character, these walks served the practical function of linking church to chapter-house, chapter-house to refectory, and so on. Moreover, they provided an ideal backdrop for processions and other ritual events.

Physical Qualities

THE basic principles underlying the form of the monastic cloister were already well established by the early 9th century, as is witnessed by the celebrated plan of the Carolingian abbey of St Gall.11 In particular, the St Gall plan shows the cloister to the south of the church, tucked into the angle between nave and transept. In the event, this was the pattern followed by the vast majority of medieval religious houses, and is far and away the most common arrangement among abbeys of the Cistercian order. It was true, for example, of the order's great mother house at Cîteaux (Côte-d'Or), and likewise at St Bernard's abbey of Clairvaux (Aube) (Fig. 2).12 In so far as one can tell, it also seems to have been the case at the majority of the early foundations in Burgundy and neighbouring Champagne.13 Nevertheless, it is clear that on occasion particular factors led to the abandonment of the preferred norm. Either through choice, or the lack of it, communities were sometimes prepared to opt for a cloister north of the church.14 This occurred quite early at Cîteaux's elder daughter at Pontigny (Yonne), for instance, and there is no shortage of other examples spread across all areas of France, as at Flaran (Gers), Fontfroide (Aude), Obazine (Corrèze), Silvacane (Bouches-du-Rhône), Le Thoronet (Var), and Vaux-de-Cernay (Seineet-Oise).15 Beyond France, well-known examples of northern Cistercian cloisters include Eberbach and Maulbronn in Germany, Moreruela and Poblet in Spain, Alcobaça in Portugal, Melrose in Scotland, and Höre in Ireland.16 Even so, we are prepared to speculate that fewer than 30 per cent of white monk abbeys followed this pattern.

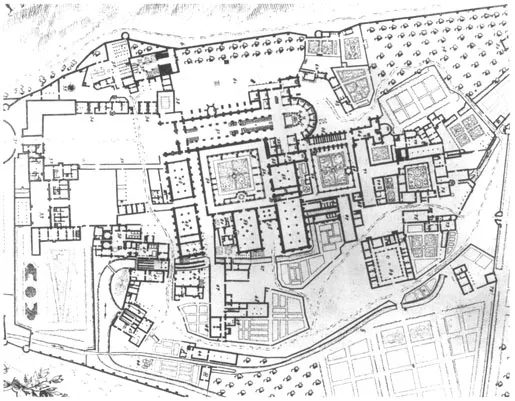

FIG. 2. Clairvaux Abbey (Aube): detail of a ground plan by Dom Nicolas Milley, 1708 Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Among the houses of England and Wales, northern cloisters were certainly in a minority (Fig. I). No more than thirteen have been recorded so far — compared to fifty-seven southern examples — representing a figure of just under 20 per cent.17 Interestingly, none of these thirteen was located in the north of England. The majority lay in the west, and perhaps the south-west in particular. The better-known sites with proven northern cloisters include Buildwas, Combe, Dore, Forde, Stanley, and Tintern.18 By and large, the literature which mentions this fact tends to attribute it to topographical factors, and especially to the practicalities of water supply and drainage.19

Turning to the shape and size of the garths themselves, the first point to note is that the Cistercians clearly showed a preference for a symmetrical four-square monastic layout, as depicted for example on surviving early plans of Cîteaux and Clairvaux (Fig. 2).20 Yet beyond this we have no real way of knowing what instruction founding communities may have been given on setting out their cloisters at an appropriate scale. In any case, it should be remembered that both the shape and size of any particular garth could be modified over time, in line with a major rebuilding programme on the abbey church or monastic buildings.

In attempting to summarise the conclusions which may be drawn from the material in England and Wales, it may not be unreasonable to think of most Cistercian cloister garths as sitting within a median range, few of them varying by more than 20 per cent larger or smaller from a 100 ft square.21 The outstanding exception at the larger end of the scale was the garth at Byland, which measured a staggering 145 ft (44.2 m) square and covered a total ground area of 21,025 sq. ft (1,953 sq. m). In terms of broad comparison, it is instructive to compare this garth with those at the two wealthiest Benedictine houses in England. In this respect, the cloister at Byland was larger than that of Glastonbury, and was only marginally exceeded by the beautiful 13t...