![]()

1

More than a feeling

The study of emotion and its development

Trying to define emotion

The aim of this book is to examine the features and possible causes of children’s emotional development, from infancy to adolescence. Yet what exactly does that entail? Although most of us know what we’re talking about when we talk about our own emotions, it is notoriously difficult for psychologists to define the concept of emotion. The definitions they offer often seem rather abstract. For example, in their authoritative review of studies of emotional development in the Handbook of Child Psychology, Saarni, Campos, Camras, and Witherington (2006) proposed the following ‘working definition of emotion’: ‘Emotion is … the person’s attempt or readiness to establish, maintain, or change the relation between the person and his or her changing circumstances, on matters of significance to that person’ (p. 227; quoted from Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004). Saarni and her colleagues go on to distinguish the concept of feeling from the concept of emotion, and argue that what laypeople refer to as their feelings is not the core of emotion.

It is certainly true that the student of emotional development must study many different things, beyond an individual’s self-reported feelings. Emotion is felt and expressed through physiological reactions and physical actions, and interpreted through thoughts and words. Nonetheless, there is some danger that, when acknowledging the complexity of the process of emotional development, we might lose sight of its distinctive content. Furthermore, the very general definitions are somewhat circular: How do we determine what is significant to a person without any indication of an emotional reaction? Therefore, in this book, we shall not dwell at the outset on definitional complexities. Rather, this book takes an empirical approach to the study of emotion, by focussing on particular categories of emotions, more or less in the sequence in which they consolidate from infancy to adolescence. We will then return to the vexing definitional issues in the final chapter.

Differentiation theory and its critics

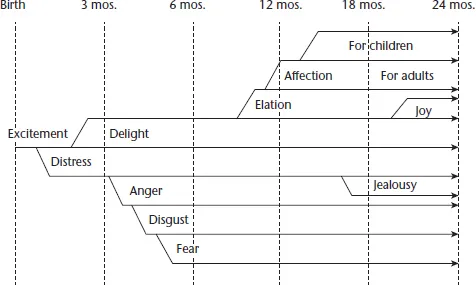

The organisation of the book has been influenced by the classic theory of the differentiation of emotion offered by Katherine Banham Bridges (1932). Bridges, who was born in Sheffield, UK in 1897, became the first person to pursue an honours degree in psychology at Manchester University. After moving to Canada, she became the first woman to receive a PhD in psychology from the University of Montreal. Bridges argued that the original emotion experienced by infants is excitement, which becomes differentiated into interest and distress (Figure 1.1). On the basis of her observations of 62 infants in a foundling hospital in Montreal, Bridges argued that:

The earliest emotional reactions are very general and poorly organized responses to one or two general types of situations. As weeks and months go by the responses take on more definite form in relation to more specific situations … in the course of genesis of the emotions, there occurs a process of differentiation… . In this manner slowly appear the well known emotions of anger, disgust, joy, love, and so forth. They are not present at birth in their mature form.

(p. 324)

The differentiation hypothesis put forth by Bridges was in line with more general theories of emotion set forth by her contemporaries. For example, Allport (1924) claimed that ‘At the beginning … of the life of feeling there is little to differentiate the emotional states beyond the mere qualities of pleasantness and unpleasantness. The child has feelings of unpleasantness, but not yet definite unpleasant emotions’ (p. 93).

Figure 1.1 Katherine Banham Bridges’ classic model of emotional development

In the pages that follow, I shall draw on the classic scheme presented by Bridges as an organisational framework for this book. Bridges claimed that the ‘original emotion’ (p. 325) was excitement (a term that subsequent emotion theorists might equate with arousal), which soon differentiated into two general tendencies, interest and distress. According to Bridges, distress then differentiated into the primary negative emotions (fear, anger, disgust and sadness). Accordingly, we shall first examine infants’ initial expressions of distress and pleasure (crying and smiling) and then the primary negative emotions, before proceeding to discuss more complex emotions, including the so-called moral emotions that emerge later in childhood and are bound up with the development of a sense of self.

A few decades after Bridges undertook her study of infants, the issue of differentiation of emotion over time became a matter of considerable controversy. Later theorists working within an evolutionary perspective, such as Silvan Tompkins (1963), Paul Ekman (Ekman, Friesen, & Ellsworth, 1972) and Carroll Izard (1971), disagreed with Bridges’ differentiation theory. They proposed instead the theory that discrete facial expressions of emotions such as fear, disgust or anger have been selected for in evolution. They claimed that these expressions of distinct emotions were seen across human cultures and already shown by young infants, even in the first months of life (e.g., Ekman, 1993; Izard, Huebner, Risser, & Dougherty, 1980). This latter approach became known as the differential emotions theory. A body of work testing differential emotions theory has focussed on patterns of emotional expression that could be discerned across ages and cultures.

Over the last few decades, the differential emotions approach set forth by Ekman, Izard and their colleagues has shaped much research on emotional development in infancy. However, in recent years, it has received some criticism. Some psychologists claim that emotional development does not entail the emergence of discrete emotions nor entirely undifferentiated ones but rather the consolidation of different components of emotions over time (e.g., Witherington, Campos, Harriger, Bryan, & Margett, 2009). Still other theorists question whether very young infants can experience emotion at all, because they cannot yet distinguish between themselves and other people (Sroufe, 1995).

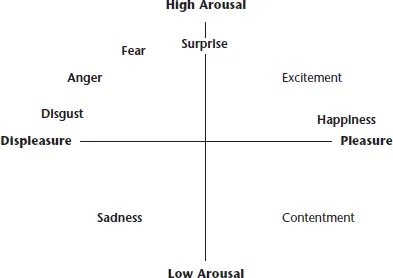

One analysis of children’s understanding of emotion concepts, as measured by their spontaneous references to different emotions and their performance on discrimination tasks (Widen & Russell, 2008), returned to an updated differentiation model of emotional development that echoes Bridges’ earlier theoretical framework. Widen and Russell’s circumplex model features two orthogonal dimensions, one measuring the degree of a person’s arousal and the other the degree of pleasure/displeasure he or she experiences (Figure 1.2). In Widen and Russell’s model, surprise is an emotion that reflects a high degree of pure arousal. The negative emotions of fear, anger and disgust also show high arousal, whereas sadness reflects low arousal. The positive emotion of happiness reflects a moderate level of arousal. Their empirical analyses of children’s understanding of emotion labels during early childhood also show a gradual differentiation from a basic distinction between positive and negative emotion to a more nuanced understanding of the different negative emotions (Widen & Russell, 2008). Thus, although Bridges theorised about infants’ observed expressions of emotion, and Widen and Russell focussed on children’s use of emotion language, both theories point to a gradual differentiation of negative emotional experience.

Figure 1.2 A two-dimensional model of children’s understanding of emotions

My own use of Bridges’ classic account of emotional development as an organising framework for this book certainly does not imply unqualified acceptance of this early theory. Although criticisms have been levelled against the theory of differential emotions in recent years (e.g., Camras & Shutter, 2010), and some elements of Bridges’ differentiation theory may be worth revisiting, caution is still needed. Children’s emotions may not differentiate in the exact way that Bridges proposed, and, if they do, the underlying processes that lead to differentiation may reflect learning and emotional socialisation, as well as biological maturation. What is most important, however, is the fact that Bridges’ account was a developmental theory, resting on the premise that important developmental changes take place in both the expression and understanding of emotion over infancy and childhood. For example, children’s abilities to associate felt emotions with bodily sensations show considerable development between childhood and adulthood (Hietanen, Glerean, Hari, & Nummenmaa, 2016).

Therefore, because it sets out an explicitly developmental perspective, Bridges’ scheme still provides a useful conceptual framework in which to consider what actually happens during emotional development. We shall return to the issue of developmental processes that underlie emotional development in the final chapter of this book.

Key dimensions of emotional development

Within and across these different domains of emotional experience, fundamental questions must be asked about what a child’s emotional development actually entails. In this book, we shall concentrate attention on three important components to the development of emotion: the expression of emotion (and its relation to inner emotional experience), the understanding of emotion (one’s own emotions and those of other people) and the regulation of emotion. Emotion is regulated both through internal physiological and cognitive processes and through learning about the social rules that control displays of emotion in particular families and cultures. Developmental psychologists have provided evidence for change over time and continuity of individual differences with respect to each of these three components of emotional development.

The expression of emotion

In humans, emotion is expressed through different channels: the face, the voice, the hands and the physiological reactions of the body. Ever since Darwin’s (1872) treatise The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals was published, emotion researchers have debated evidence about the universality of human emotion and its biological basis. Given the prominence of differential emotions theory in the latter part of the twentieth century, much empirical work has been conducted within the theoretical framework of evolutionary theory, focussing on specific configurations of the facial musculature that are associated with primary emotions such as anger or sadness. These distinct patterns of facial configurations can be discerned across cultures (Ekman, 1972) and identified as early as the first year of life (Field, Woodson, Greenberg, & Cohen, 1982), which supports claims from the differential emotions theorists that the morphology of the human face and its underlying muscles has been selected for in the course of evolution.

Such studies of infants’ facial expressions draw attention to the early origins of emotion; however, they also raise the theoretical question of whether outward emotional expressions provide direct evidence for inner emotional experience. For example, does the child who shows a typical expression of facial anger (Figure 1.3) experience rage in the same way an adult would? Is the outward expression a veridical index of inner experience? Or does the facial expression precede a more mature understanding of anger, which in turn informs the inner experience? Should the adults who care for the child interpret the expression as being a true indication of anger, as an adult would understand that, or is it more helpful to consider it a signal of more global distress?

Figure 1.3 Is this child expressing anger?

In the chapters that follow, we shall consider this thorny issue with respect to the primary negative emotions that emerge from initial distress: disgust, fear, anger and sadness. Bridges’ theory of a differentiation process is still germane to our understanding of the emergence and subsequent development of these negative emotions.

Emotional understanding

In any given situation, how do we know what we’re feeling? On what basis do we guess what other people are feeling? Emotional experience clearly has a cognitive, interpretational dimension.

Understanding our own emotions

In a classic account of the nature of emotion (the James-Lange theory), it was argued that our observation of our own reactions to emotion-provoking situations tells us what we are actually feeling (James, 1894). For example, if we are walking down a deserted street, late at night, hear footsteps behind us, and begin to hurry along, breaking into a run, it could be argued that we interpret our emotions in accordance with the physical and physiological reactions of our own bodies. In other words, if we’re running, we must be afraid.

Although the James-Lange theory was challenged by early neuroscientists (Cannon, 1927), who demonstrated that animals whose cerebral cortices had been removed still expressed emotion, the James-Lange legacy is still felt in more modern theories that emphasise people’s cognitive construction of their own emotions (e.g., Russell, 2003). However, contemporary emotion theorists must attempt to reconcile cognitive perspectives on emotion with the findings emerging from affective neuroscience, in particular, neuroimaging studies of alert human brains. This new body of evidence draws attention to relations between brain structures that underlie physiological responses to emotion-provoking stimuli and cognitive representations of emotional experience.

Understanding other people’s emotions

Human beings pay attention to each other’s emotions from the first days of life onwards: Even newborn infants are sensitive to each other’s cries (Sagi & Hoffman, 1976). However, infants do not yet possess a theory of mind, i.e., an understanding that other people have thoughts, feelings and intentions. Understanding that other people have emotions and desires appears to develop before understanding that other people have thoughts and beliefs (Wellman & Woolley, 1990), which further underscores the salience of emotion in infants’ worlds. It has long been thought that infants’ growing understanding of their own mental life is influenced by their growing understanding of the mental lives of others, in a reciprocal and dialectical fashion (Baldwin, 1895), and so the understanding of other people’s emotions may help children to understand their own. This process is apparent in the phenomenon of social referencing, which occurs when infants who are confronted with a situation that could be pleasant or dangerous consult the emotional expressions of their caregivers before expressing their own emotion; the caregivers’ expressions guide the infants’ choices to approach or avoid the ambiguous situation (e.g., Campos, Thein, & Owen, 2003). We shall return to this topic of understanding other people’s emotions when discussing the social emotion of empathy for another person’s feelings in Chapter 9.

Emotion regulation

Physiological regulation

The important organs of our bodies are all involved in the experience and regulation of emotion; when we talk about our emotional reactions to the things that happen to us, we say that we feel things ‘in the pit of our stomachs’; we may feel ‘breathless,’ or ‘break out into a sweat,’ or feel ‘tears coming to our eyes.’ The experience of emotion is bound up with these bodily reactions, and the reactions are regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the pathways of neural connections that transmit information from the brain to the visceral organs and back a...