- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Knights Templar in Britain

About this book

The Knights Templar In Britain examines exactly who became knights, what rituals sustained them, where the power bases were, and how their tentacles spread through the political and economic worlds of Britain before their defeat at the hands of the Inquisition some two hundred years later.

Founded in the early twelfth century, the mysterious Knights Templar rose to be the most powerful military order of the Middle Ages. While their campaign in the Middle East and travels are well-known, their huge influence across the British isles remains virtually uncharted. For readers interested in Medieval History.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Knights Templar in Britain by Evelyn Lord in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR: KNIGHTLY MONKS OR MONKISH KNIGHTS?

In the year 1128 ‘Hugh of the Knights Templar came from Jerusalem to the king in Normandy; and the king received him with great ceremony and gave him great treasures of gold and silver, and sent him thereafter to England, where he was welcomed by all good men. He was given treasures by all, and in Scotland too; and by him much wealth entirely in gold and silver was sent to Jerusalem. He called for people to go to Jerusalem. As a result more people went, either with him, or after him, than ever before since the time of the first crusade, which was in the day of pope Urban: yet little was achieved by it. He declared that a decisive battle was imminent between Christians and the heathen, but, when all the multitudes got there, they were pitiably duped to find it was nothing but lies.’1 This is the first mention of the Knights Templar in the British Isles.

In order to trace the origins of the Order we must cross the sea to the Holy Land and go back in time to 1099 when Jerusalem was ‘liberated’ from the infidels by the First Crusade, and placed under the Christian rule of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The liberation of Jerusalem had a parallel spiritual liberating effect on Western Christendom that became focused on visiting the holy sites associated with the life of Christ. Pilgrims flocked to the Holy Land. They went to satisfy a spiritual hunger, they went as sightseers and tourists, they went to bring home holy relics, but above all they went to gain absolution from their sins through visiting the holy shrines. Alas, the enthusiastic but ill-prepared pilgrims were a prey for robbers, Saracens and wild animals. Many never returned to tell of their adventures. They died of exhaustion and privation or were slaughtered as they travelled the recognised pilgrim routes. At Eastertide 1119, 300 pilgrims were killed and 60 taken prisoner by the Saracens as they took the road from Jerusalem to the River Jordan.2 Such tragic loss of life could not be allowed to continue. William, Archbishop of Tyre, wrote that a group of nine ‘holy and pious knights dedicated themselves to the protection of pilgrims. Since they had neither a church nor a fixed place of abode, the king [Baldwin II of Jerusalem] granted them a dwelling place in his own palace on the north side of the Temple of the Lord’. The holy and pious knights who were given a dwelling in the Temple precincts became the Knights Templar.3

Walter Map, Archdeacon of Oxford and a clerk in the English royal household, writing in the 1170s, embroidered this account, adding dramatic details:

There was a certain knight called Paganus after a village in Burgundy of the same name, who went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. There he was told that pagans were in the habit of attacking Christians who went to the horse-pool for water and that the Christians were often slain. He tried as far as he could to defend them, hiding then darting out in the nick of time…

The Saracens were amazed, and encamped on the spot in such numbers that no one could dream of facing them, and the reservoir was abandoned. But Paganus was no coward and procured a means of help for God and himself. He obtained from the regular canons of the Temple a large hall within the precincts of the Temple of the Lord, and there sufficing himself with humble attire and spare diet devoted all his expenditure to arming and horsing a band of companions.4

The third major source on the origins of the Templars, Matthew Paris, the monk of St Albans, writing c. 1236–59, suggests that the nine knights took up monastic vows to gain remission for their sins and then roamed the country hunting infidels.5 A fourth source is Michael the Syrian, considered to be unreliable.

All three reliable sources above were written after the event and relied on oral and hearsay evidence to reconstruct the early years of the Templars. William of Tyre, who died in 1186, was the closest in time and place to the beginnings of the Order. Paris is the furthest removed, whilst Map wrote to entertain. He is probably the least reliable, especially as he had a cavalier attitude towards chronology, starting his work with a quotation from St Augustine: ‘In time I exist, and of time I speak. What time is I know not.’6

Both William of Tyre and Matthew Paris disliked the Templars, seeing them as rivals for ecclesiastical power and resenting their special relationship with the Pope. Entries in their chronicles reflect these attitudes, showing the Templars as proud, arrogant and unreasonably wealthy. Christian defeats in the Holy Land were blamed on this pride. The bias in Paris's account must be seen within the context in which he lived. He was a Benedictine who wished to maintain his Order's status, and he had a personal animosity towards the Pope. Sophie Menache and Helen Nicholson suggest that part of Paris's handling of the Templars was due to a hardening of attitudes towards the military orders in the thirteenth century when he was writing, and interpreting his chronicles depends on an understanding of how he viewed history and his perception of events. Nicholson likens Paris's accounts of the Templars to ‘tabloid journalism’. Menache suggests that we take the accounts as evidence of thirteenth-century attitudes rather than historical accuracy. C.G. Addison, writing in the nineteenth century, also bids the reader beware of Paris's version of the Templars, and accuses him of prejudicing subsequent generations against the Order.7

Nicholson suggests that there is some doubt about the date that the Order was founded, whilst Barber notes that although most sources give this as 1118, it was more likely to have been 1119, after the massacre of the pilgrims at the pool.8

HUGH DE PAYENS

Little is known about Hugh de Payens, the first Grand Master of the Templars. He came from Payens, a village in Champagne on the left bank of the Seine, and was a vassal of the Count of Champagne. It is possible that he was in the Holy Land, having joined the First Crusade after the death of his wife. According to Scottish and Freemason tradition, his wife was Katherine St Clair, who came from the French branch of the Scottish Sinclair family. As the Sinclair family were to become the Grand Masters of Scottish Freemasonry, this would be a convenient link with the past.

Founder knights

The founder knights were:

Godfrey of St Omer (Picardy)

Geoffrey Bisot or Bisol

Payen Montdidier (Picardy)

Archimbaud de St Armand (possibly Picardy)

Andre de Montbard (he may have been related to Bernard of Clairvaux and came from either Burgundy or Champagne)

Rossol or Roland

Gondamar

It is probable that they had travelled to the Holy Land as a group. Hugh died in c. 1136 and was succeeded as Grand Master by Robert of Craon.

THE TEMPLARS’ AIMS

Was the original intent of the Templars to protect pilgrims, or was their prime aim to lead a monastic life? William of Tyre writes that they dedicated themselves to God, taking vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, and then the Patriarch and other bishops enjoined them for the remission of their sins ‘that as far as their strength permitted, they should keep the roads and highways safe from the menace of robbers and highwaymen, with especial regard for the protection of pilgrims’.9 As the founder members came from a warrior class and were trained in arms they may have suggested this role for themselves, but the Patriarch could have seen this as a way of harnessing their warlike energies. Bernard of Clairvaux described them as ‘superbly trained to war’, but Peter Partner, in his book The Murdered Magicians, quotes an early letter from Hugh de Payens in which he declares that the knights wanted to work for God rather than others.10

How did outsiders perceive the Templars in their early years? Was it as knights or as brothers of a religious order? One way of answering these questions is to look at the way in which the Order is described in the charters granting them lands and rents. Although there are problems with this method, as the descriptions may show how the scribe rather than donor perceived the Order, it does give some background on contemporary perceptions. The charters that have been used are those in the Marquis D’Albon's Cartulaire General de l'Ordre du Temple. The Marquis collected evidence from across Europe and printed it in 1913. For the earliest period there are 21 relevant charters (Charters IV–XXIX). One is a grant to ‘God and the Brothers of the Temple’ and another to ‘Master Hugh and the Poor Knights of the Temple, present and future…’. The rest have no mention of the members of the Order as brothers or members of a religious order. The number of grants increased dramatically in 1130 to 127 (Charters XXX–CCII). Of these, 20 refer to the Order as ‘brothers and knights’. One makes a distinction between knights and brothers, giving land to ‘Lord God, the Holy Knights of the Temple of Solomon and the Brothers of the same’, adding another dimension to the problem. It is noticeable that English grants invariably refer to the ‘Knight Brothers of the Temple’. In the 1120s one charter refers to the Order's poverty, and two in the 1130s (Charters CXIV, CCXILX–CCLVI, CCCCL–CCCCLXXXVI). A grant from the Templars dated 30 August 1140 shows how they referred to themselves. It starts ‘In the Name of God, we, Brothers of Jerusalem, Knights of the Temple of Solomon’, indicating perhaps that the members of the Order saw themselves first as monks and second as knights.

The charters also enable us to understand some of the reasons for making grants to the Order. In the 1120s five grants were made for the sake of the soul of the donor and his or her family, past, present and future, and two were made in memory of a son. The other charters did not state the reason behind the grant. In the 1130s, in 24 cases it was for the soul of the donor and the donor's family, and in eight cases the grants were for the redemption of the donor's sins and absolution. Only two grants were specifically made in order to help the defence of the Holy Land.

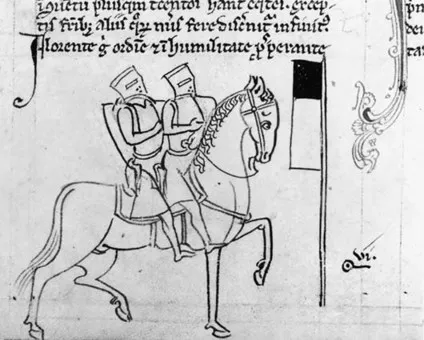

What conclusions can we draw from this sample? It would seem that to those granting land and rents to the Templars they were recognised mainly as knights rather than monks. The image of a knight would have been one the donors could relate to and understand from their own experience. The idea of poverty in relation to the Order was not uppermost in the minds of the donors, and the promotion of the Order's poverty may have been for the purpose of acquiring property. The legendary poverty of the Order has been assumed from them calling themselves poor knights, and from their seal, which represents two knights on one horse (Plate 1.1). Of course this may represent fellowship rather than poverty.

Plate 1.1 Two Templars on one horse with the banner of Beausant, as illustrated by Matthew Paris

The British Library. BL Royal Ms 14, fol. 42v

The British Library. BL Royal Ms 14, fol. 42v

The reasons for making grants to the Order were primarily personal and concerned with the spiritual health of the donor and the donor's family, ancestors and successors, rather than with the defence of the Holy Land and the protection of pilgrims. The indirect result of the grants were resources that could help in this, but the direct aim of many of the donors was self-preservation and deliverance from the pain of Purgatory. Although it has been argued that feudal society was not based solely on obligations to family and kin, but depended on the wider obligation of overlord and vassal, charters such as these examples show that within the private sphere obligation to the family and its spiritual well being was of great importance.11

The idea of a military order of monks was a totally new concept that went against the precepts of monastic life that forbade the spilling of blood. The foundation of the Templars created a body of men who saw fighting the infidel as an act of devotion. Whilst the monk spent his life in the monastery in continual prayer and praise to God, the monkish knight spent his day fighting for the glory of God. The Knights Templar were permanently at war, and war became a version of prayer for them.

The image of knighthood was transformed by this, from one which fought for personal vengeance and material gain to one which fought for Christian ideals. We should not forget that the original founders of the Order came from the knightly class. War was their business and defined their self-image. The Knights Templar and the other military orders added piety to a knight's code, and began the modification of war for gain to a just war that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Name Evidence and Its Uses

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Glossary

- Events in the Holy Land

- 1. The Knights Templar: Knightly Monks or Monkish Knights?

- 2. The Templars in the British Isles: London and its Suburbs

- 3. The Templars and the Countryside: Eastern England

- 4. The Templars in the Countryside: North-eastern England

- 5. The Templars in the Countryside: The Midlands, the Chilterns and Oxfordshire

- 6. The Templars in the Countryside: The Welsh Marches, Wales, the West and Southern England

- 7. The Knights Templar in Ireland and Scotland

- 8. The Templars and the Plantagenets

- 9. The Templars as Bankers

- 10. The Trial and Fall of the Templars

- 11. The Templars in Fact and Fiction: Debates, Myths and Legends

- Notes

- Appendix Templar Records in The National Archives

- Gazetteer of Templar sites

- Bibliography

- Index