![]()

Part 1

Developing subject knowledge

![]()

Partnering theory

and practice in

mathematics teaching

Ian Campton and Mary Stevenson

The relationship between the quality of mathematics teaching and the subject-related knowledge of the teacher is widely acknowledged as an important one. Also, the process of teaching stimulates a growth and reconstruction of knowledge, so this relationship is two-way. In this chapter we explore ways that the content knowledge of pre-service teachers can be developed in practice, and the role practice-based mentors have in facilitating these processes. The importance for practice-based mentors and pre-service mathematics teachers of nurturing a strong focus upon the subject will be explored. In placement contexts characterised by multiple competing agendas, we believe this is essential in the ongoing improvement of mathematics teaching at all levels.

Introduction

Many analogies have been used to depict the ways in which students develop an understanding of mathematics. One of them, the ‘learning landscape’ as constructed by Twomey Fosnot and Dolk (2001), describes how students negotiate the terrain of an area of mathematical learning in order to reach the mathematical understanding that lies on the horizon. The learning journey involves visiting the landmarks which are the key ideas and concepts behind the topic necessary for a comprehensive understanding of the mathematics that lies on the horizon. Roaming aimlessly around this landscape is a futile learning experience for students and something that should be avoided. A guide, in the form of a mathematics teacher, is therefore required to assist in their passage from the starting place to the horizon. If this is to be a smooth passage, the teacher, as with all good tour guides, needs to maintain an intimate knowledge of the landscape and the many ways in which it can be successfully negotiated. Not only is this learning terrain complex, dotted with misconceptions and barriers to learning, but the students exploring it all have different starting points and will probably take different routes. Consideration must therefore be given to the knowledge that equips the preservice teacher for the task of teaching mathematics. Research findings in this area offer the mathematics teaching community at all levels some powerful and transformative ideas.

Attention to these ideas helps teachers to become more expert in the field and able to make informed judgements about government initiatives and other competing agendas. Ultimately, attention to the findings of research will lead to ongoing improvement in mathematics teaching for all. Much has been written about the development of mathematics subject knowledge for teaching, and yet there remains a clear mismatch between the public, policy maker and layperson's views of what subject knowledge means, and the subtler, more complex characteristics gained from research. Is the possession of a good grade in secondary school mathematics sufficient to equip someone to teach primary school students? Is the possession of a degree in mathematics sufficient to enable someone to teach mathematics in a secondary school? Most of those who work in education would agree that whilst formal academic qualifications are important, they are not sufficient alone for successful teaching. Teachers need a wider, more nuanced, specialised knowledge of the subject, which relates to the curriculum and the needs of their students. It is not sufficient to ‘know’ some mathematics oneself: one needs, amongst other things, to be able to ‘unpack’ the ideas in order to make them accessible to learners, to be able to make careful choices of examples and tasks, and to be able to respond flexibly to the responses of students to those tasks. So what exactly does this specialised knowledge consist of, how is it constructed and, perhaps more importantly for mentoring pre-service teachers, how is it developed?

What do we mean by subject knowledge for

teaching?

The field of mathematics subject knowledge for teaching has been widely researched, and various models have been proposed in defining its contents and structure. Inevitably there are similarities between these models, making the sorting into discrete categories rather imprecise. With overlaps and blurred edges, an awareness by both mentor and pre-service teacher of the subject knowledge for teaching should not necessarily concern the organisation of these different categories, but rather their content, which is perhaps more important and beneficial to improving practice.

Similarities in the research field can be attributed to the fact that much recent research into knowledge for teaching is founded upon the seminal work of Lee Shulman (1986). Shulman questioned the distinction between content and pedagogy, and asked how these are related in the process of teaching. He discussed the connections between knowing and teaching, probing how learning for teaching might occur, and noted that “mere content knowledge is likely to be as useless pedagogically as content-free skill” (p. 8). He suggested that it is important to think about how these aspects of a teacher's repertoire are blended together.

In shifting the focus away from the generic aspects of teaching, Shulman proposed a three-part model of content knowledge consisting of subject matter content knowledge (SMK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) and curricular knowledge (CK). The major contribution to this model was his concept of the existence of pedagogical subject knowledge, i.e. subject matter knowledge for teaching. Shulman's ideas are not subject specific; they apply across the curriculum. In the context of mathematics, recognition of pedagogical subject knowledge means that there is knowledge that teachers need to have, and there are ways in which they need to hold that knowledge, which are specific to the requirements of teaching the subject and which other people who use mathematics do not necessarily have.

Subject matter knowledge

In essence, this category is concerned with detailed knowledge of the subject with such depth that it has two fundamental constituent parts as identified by Schwab (1978): substantive knowledge and syntactic knowledge. For a mathematics teacher at any level, substantive knowledge is the knowing of facts and concepts, whilst syntactic knowledge is that which is required for the process of doing mathematics. Shulman believed that teachers should not only know that something is the way it is but also why it is this way, and that they must understand why one topic is fundamental to a subject and others are secondary, knowledge he considers to be important in making pedagogical judgements. The importance of subject matter knowledge in making pedagogical judgements is something that is rarely contested, and it is a readily accepted view that teachers must have a solid knowledge of the subject they teach. But what is not so widely acknowledged is the extent of this knowledge and how deep it needs to be.

The irrelevance and relevance of formal

mathematical qualifications

In returning to ideas we introduced at the start of this chapter regarding the relationship between subject knowledge for mathematics teaching and formal qualifications in mathematics, the answers to the questions posed in the introduction of this chapter need exploring. Research shows that there is no relationship between teachers' level of formal qualifications in mathematics and their effectiveness in mathematics teaching (Eisenberg 1977; Begle 1979; Askew, Brown, Rhodes, Johnson & Wiliam 1997). That is not to suggest that formal academic qualifications are not important or necessary. What this does show is that something else is going on: effective teachers of mathematics have other attributes, other knowledge areas which are often hard to pin down and measure, whilst formal qualifications are easy to quantify and record.

For the pre-service teacher and his or her mentor, this should be reassuring. For what it suggests is that developing one's subject knowledge for teaching is not really about studying high-level mathematics courses, although some pre-service and novice teachers will have done this, and enjoyed and succeeded in it; rather, it is about paying attention to the detail of the mathematics with which one is working, and endeavouring to gain a deep and connected understanding of this mathematics with regard to the needs of the learners. In particular in the context of mentoring, it is about developing openness to new ideas and being prepared to re-learn mathematics in different ways. As times change, the ways in which preservice teachers learnt mathematics may be different to those used in the present-day classroom; some examples of this can be seen below. This can be challenging and uncomfortable for pre-service teachers, and mentors need to recognise this.

Examples of changing teaching methods

Primary

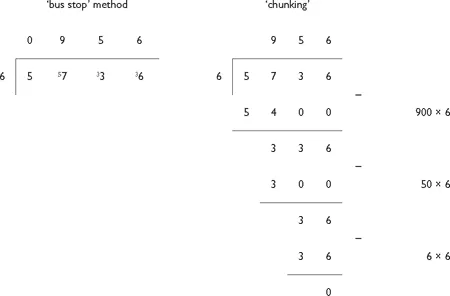

Division algorithms – the ‘bus stop’ method vs. the ‘chunking’ strategy, which is a new approach to many pre-service teachers. The ‘bus stop’ method is a written algorithm where the divisor is ‘divided into’ a uniquely partitioned dividend and remainders are ‘carried over’ to the next column. The ‘chunking’ strategy exploits the quotative aspect of division and uses a sophisticated method of repeated subtraction where ‘chunks’ of the divisor are removed from the dividend rather than repeatedly removing. So, for 5736 ÷ 6 using the ‘bus stop method’, 6 is ‘divided’ into 5 which does not go, so the 5 is ‘carried over’ into the next column to make 57. 6 into 57 goes 9 times with a remainder of 3, again ‘carried over into the next column’, and so the procedure continues. The ‘chunking’ strategy involves calculating how many 6s make up 5736 through the process

Figure 1.1 Methods of division

of repeated subtraction. As 5736 is a large dividend, constantly taking 6 away is time consuming and so ‘chunks’ comprising of groups of 6 are subtracted.

Secondary

Solving linear equations – the traditional ‘change side, change sign’ method vs. the ‘balancing’ approach. For example:

The first stage of solving the equation 3x + 4 = 19 by the traditional procedural approach moves the +4 to the other side of the equation where it becomes −4, as shown in Figure 1.2.

The ‘balancing’ approach would be to subtract 4 from each side in order to remove the +4 term and isolate the 3x, whilst still keeping the equation balanced, as shown in Figure 1.3.

| |

Figure 1.2

Solving a linear equation by a ‘traditional’ approach | Figure 1.3

Solving a linear equation by a ‘balanced’ approach |

In a study to identify what it is that primary school teachers know, understand and do which enables them to teach mathematics effectively, Askew et al. (1997) found that being a highly effective teacher of mathematics was not associated with having an Advanced level or degree in the subject. As the development of basic number concepts is at the heart of the primary school curriculum, these findings are perhaps not surprising. After all, how often are primary school teachers required to draw upon either the substantive or syntactic knowledge of such higher-level mathematics and such things as the formulation of differential equations? What is important, therefore, is not so much a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of academic mathematics, but more an understanding of the mathematics within the curriculum that is taught and how critical this is ...