![]()

Chapter 1

The nonlinear paradigm

The map is the treasure.

Will Rood, mathematician

Psychotherapy is a complex affair. Consider what it means to be human: each body capitalizes on millions of years of biological evolution to form the most complicated object in the known universe, the human brain. Each brain supports consciousness by parallel processing 100 billion neurons, an amount that approaches the number of stars in the Milky Way. Each neuron communicates with approximately 100,000 of its near and distant neighbors to result in more neuronal synaptic interconnections in a single human brain than the number of known particles in the universe - 10 followed by a million zeros (Edelman, 1992).

The biology of the isolated brain is just the beginning. In life, the brain and psyche develop out of a tangle of relationships with others. Give an infant all she needs physically, but deprive her of loving touch and she will wither as if starving. From the moment of conception, complicated feedback loops link mind to mind, mind to brain, and mind to body. Multiple, parallel interactions continually connect self with other, self with self, and self with world, each level operating according to intrinsic dynamics on different time scales. From infancy on, ongoing interactions with family, friends, strangers, and culture at large lead to absolute uniqueness in the minute-to-minute co-creation of self and other. Yet the uniqueness of each moment is easy to overlook. Ongoing consciousness is based on language that categorizes by similarities and analyzes by breaking experience down into digestible bits. Linear thinking characterizes ordinary logic and the working of the brain's left, more verbal hemisphere.

By contrast the nonlinear perspective characteristic of contemporary science is more typical of the nonverbal, pattern-seeking, right hemisphere and reveals a different universe. In the midst of staggering complexity, system parts are inseparable from the whole. Holistically perceived, each moment contains an infinite amount of information for which words do little justice. With interdependence and open boundaries between one complex system and another, distinct borders dissolve. Dancing in continual flux, each part is fully enfolded by dynamics of the whole. No wonder the nonlinear realm is where mystics have played for millennia (see Figure 1.1).

Given such a kaleidoscope of flux and entanglement, how do therapists converge to clear vision? How do we distinguish body from mind, inner beliefs from outer reality, one psyche from another, personality from culture? How do we put together an infinite amount of information to do our job? Must we even answer such questions to work effectively?

Secretly most clinicians know that the work can proceed beautifully

Figure 1.1 The dance of Shiva.

Whereas the logical, rational style of the left-brain short circuits in the face of extreme complexity, the nonlinear, synthetic style of the right-brain is undaunted. This image of Shiva, derived from ancient Hindu mythology, portrays the continual dance of creation and destruction in the flux of the whole of Atman. The surrounding ring represents the universe with all its illusion, suffering and pain. The outer circle constitutes the fire of cosmos and consciousness, its inner edge lined with ocean waters. Shiva stands on the demon of illusion and ignorance. His dance is intended not only as a symbol, but also as a literal depiction of what takes place within us all at each moment, at invisible levels at the heart of consciousness. Like this book, Shiva dances at the intersection of art, science and spirituality.

without our ever knowing exactly what is going on or what will happen sometimes maybe even because we do not "know." Contemporary clinical thinkers such as Allan Schore (1999, 2003a, 2003b) attend to right-brain, implicit, nonconscious processes underlying psychotherapy. At this level, body-based responses underlying the attachment dynamics of an attuned relationship between therapist and patient can proceed without our awareness or even understanding.

Despite its underlying physiological complexity, being in relationship and doing psychotherapy does not always feel complex. When we operate smoothly, in a state of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), or with hovering attention (Freud) resembling a moving meditation, the work can seem downright simple, almost as if it completes itself. How does so much complexity translate into something so simple? What is this paradox? If formulas and templates do not easily capture the essence of human transformation, what can? Despite a process plagued by messiness, fits and starts, and frequent setbacks, how do competent therapists manage to get the job done?

The science of change

In line with the interdisciplinary field ol interpersonal neurobiology (e.g., Cozolino, 2002, 2006; Ogden et al., 2006; Schore, 2003a, 2003b; Siegel, 2001, 2006, 2007, 2008; Siegel and Hartzell, 2003; Solomon and Siegel, 2003) and those who have recognized the importance of nonlinear science to psychology (e.g., Abraham and Gilgen, 1995; Abraham et al., 1990; Barton, 1994 Butz, 1997; Combs, 1997; Dauwalder and Tschacher, 2003; Goertzel, 1993 1994, 1997; Grisby and Stevens, 2000; Guastello, 2001, 2006; Kelso, 1995 Lewis and Granic, 2002; Mac Cormac and Stamenov, 1996; Piers et al., 2007 Robertson and Combs, 1995; Shelhamer, 2006; Sulis and Combs, 1996 Thelen and Smith, 1993,1994; Vallacher and Nowak, 1994; Van Orden, 2002) and to clinical practice specifically (e.g., Butz et al., 1996; Chamberlain and Butz, 1998; Gottman et al., 2002; Levenson, 1994; Masterpasqua and Perna, 1997; Miller, 1999; Orsucci, 1998; Palombo, 1999; Pizer, 1998; Rossi, 1996; Seligman, 2005), I offer nonlinear science as a framework to understand how such questions relate to issues of clinical intuition, complexity, and creativity. Nonlinear dynamics represents the science of change, and offers metaphors and models closer to embodied experience while refining the therapist's eye to detect complex patterns. Nonlinear science specializes in facets of nature that are idiosyncratic, spontaneous, irregular, emergent, discontinuous, and unpredictable.

One important premise is that a nonlinear paradigm helps to conceptualize the early attachment dance between infant and caretaker that coordinates physiology, choreographs movements, tunes brains, and ultimately sculpts the minds of each. These ideas are especially important to Schore's regulation theory (e.g., Schore, 1999, 2001, 2003a, 2003b) and its sister science, attachment theory (e.g., Bowlby, 1969; Fonagy et al., 1995; Mam and Hesse, 1990; Sroufe, 1983; Stern, 1985). Such theories reverse how we normally conceptualize development. Rather than viewing separate individuals as they come together to form relationships, these perspectives examine how the individual psyche emerges out of relationship as the basic building block.

The precise way in which developing brains, bodies and minds self-organize in response to attuned caretaking requires nonlinear conceptions. This framework is ideal to model the implicit, often nonverbal, unconscious levels of emotional and ideational exchange. Nonlinear techniques capture coupled dynamics between people at multiple descriptive levels (e.g., Guastello et al., 2006; Levinson and Gottman, 1983). Precise, idiographic methods track unique physiological events, including significant therapeutic moments (e.g., Pincus, 2001; Shockley, 2003).

Betore introducing a detailed clinical case to offer major book themes, first I present a brief overview of nonlinear science.

Nonlinear science in a nutshell

Nonlinear dynamics spans the spectrum from the microscopic to macroscopic, from physics to biology, from neuroscience to economics. Scores of disciplines, most highly specialized and mathematically rooted, sport arcane names like "nonequilibrium thermodynamics," "cellular automata," and "free agent modeling." Though initially we may feel apprehensive about unfamiliar, technical or mathy sounding terms, they are easier to grasp than on first blush. Because the ideas align with clinical intuition already developed, to grasp them at more conscious, formal levels can prove especially powerful.

I draw primarily from three areas of contemporary science most relevant to clinicians - chaos theory, complexity theory, and fractal geometry. Chaos theory grounds us in the inevitable turmoil, discontinuities, and limited predictability of ordinary life. Complexity theory reveals how development, new order and creative change self-organize, spontaneously emerging at the edge of chaos. Fractal geometry detects complex patterns of the whole as they extend through a system's parts, including paradoxical boundaries simultaneously open and closed, bounded and unbounded. Taken together, these sciences model the deep and mysterious interpenetration between self, world, and other.

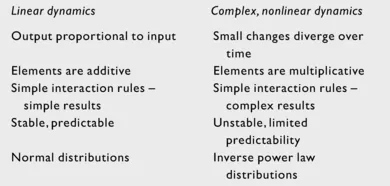

We can understand the essence of nonlinear dynamics by contrasting contemporary with traditional paradigms. Much of classical science, like Newtonian physics, is linear. In linear systems or states small inputs give rise to small outputs, while large inputs give rise to large outputs. The relationship between variables is additive, and given the relative independence of underlying aspects, cause relates to effect in ways that are dependable, repeatable, and predictable.

Science box 1.1 Linear versus nonlinear science

Linear ideas and methods are the foundation for the empirical method of classical science, where predictions are formulated and hypotheses tested in replicable designs. In linear systems or realms, simple cause and effect relationships hold because the contribution of each part is independent and additive, such that the whole is exactly the sum of the parts. Classical statistics within social sciences and clinical psychology specifically often are based on linear, normative assumptions. As we shall see, the falsity of underlying assumptions might explain why experimental results in the social sciences are often hard to replicate, and why so many experimental outcomes account for so little of the variance.

Nonlinearity is at the heart of all fields of modern science, permeating the curved geometry underlying Einstein's formulation about spacetime, the strange world of quantum dynamics, small world network dynamics and other types of highly uneven distributions by which a few people do most of the work, carry most of the power, and why the rich often get richer.

With the advent of modern computers and brain imaging, methods for capturing subtle and unique nonlinear interactions get more sophisticated. New techniques allow us to get ever closer to quantifying the complex and normally invisible ways that people's brains and bodies lock in together and influence one another, often below the threshold of consciousness. In nonlinear systems or realms, due to interdependent parts whose contribution to the whole is multiplicative, simple cause-and-effect relationships break down. The time-honored Gestalt formulation, of the whole as more than the sum of its parts, perfectly characterizes nonlinearity.

When approaching contemporary science, the question is not whether to go linear or nonlinear. Nonlinear methods do not replace linear ones. Nonlinear results are not more true or descriptive than linear ones. This is not an either/or issue partly because linear realms are included within the nonlinear. Linear states can emerge under certain, well-constrained conditions. Because the nonlinear is the broadest reaching realm, through its understanding, we gain a more direct window into life's ongoing complexity.

Everyday logic, by which we use left-brain thinking to pick apart experience, discern cause and effect, and mentally calculate our next move, is both linear and reductionistic. Reductionism involves the analysis of complex problems by breaking them down into simpler components. Imagine a mechanic who trouble-shoots a car by dismantling it, finding and replacing faulty parts, and then putting the parts back together to reconfigure the whole. Because of the repeatability of links between cause and effect, time drops out as a factor in reductionistic thinking. Whether the car is fixed now, in a week or in a month is irrelevant to the mechanics of the process

The application of the reductionistic paradigm to therapy is severely limited. We cannot take people or relationships "apart" at any level, either literally or symbolically, without destroying their wholeness. Timing is everything; the same intervention that in one moment is welcome and incisive, in the next may be intrusive and injurious. Nor can we exactly repeat the magic of a therapeutic moment, either in action or with words. Yet when Freud popularized psychoanalysis, the field emerged politically as a subdiscipline of medicine during an era when medicine was deeply steeped in reductionism. Because of these historical roots, plus persistent cultural agendas demanding predictability and control, most therapists are only dimly aware of how steeped in linear paradigms we remain.

It is my belief that human undertakings of emotional healing and psychological transformation are quintessentially nonlinear and dynamic affairs. Dynamic implies movement; and movement implies motion over time. Simply put, dynamical systems theory examines how systems change over time. Time has all too often been ignored in clinical theory, where static conceptualizations abound, such as diagnosis as a one-time, one-body, static affair or the classical conception of the unconscious where there is no time. Lack of attention to the centrality of context as well as to unique, moment-to-moment dynamics can lead to poorly designed outcome studies that attempt to reduce healing to therapeutic modalities rather than to focus on idiosyncratic elements, dynamic state changes, and nonlinear moments where real change emerges.

In nonlinear systems or states, small inputs often give rise to unexpectedly large consequences, while huge inputs sometimes have little or no impact at all. Imagine a pivotal moment during a therapy session when a tiny remark can trigger an avalanche of repercussions or surprising progress. Or consider the opposite, when what seems like a "highly significant" interpretation falls on unflappable ears. Day in and day out, these two extremes of tiny and huge inputs having disproportionate outputs constitute the nonlinear rule in contrast to the linear exception.

The nonlinear in action

With this bit of technical explanation under the belt, I turn next to a clinical case chosen specifically for its nonlinear aspects. With Sabina, no single, logical chain of thought seemed to work based on the "traditional" model of diagnosis, treatment plan, implementation and evaluation. As the re...