eBook - ePub

Neurobiology of Addictions

Implications for Clinical Practice

- 119 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neurobiology of Addictions

Implications for Clinical Practice

About this book

Bridge the gap between the physical foundations of substance abuse and the psychosocial approaches that can treat it!This groundbreaking book offers helping professionals a thorough introduction to the neurobiological aspects of substance abuse. It presents the basic information on the subject, including the various neurobiological theories of addiction, and places them in a psychosocial context. Its clear and straightforward style connects the theoretical information with practical applications. This is an essential resource for substance abuse counselors, researchers, therapists, and social workers. Neurobiology of Addictions offers sound, tested information on substance abuse issues, including:

- neurobiological theories of addiction

- integrating drug treatments and therapeutic interventions

- using neurobiology to discover substance abuse in clients of various ages

- perspectives from social work, pharmacology, biology, and neuroscience

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neurobiology of Addictions by Shulamith L A Straussner,Richard T. Spence,Diana M. Dinitto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Addiction en psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Articles

Neurobiological Causes of Addiction

Carlton K. Erickson, PhD, is Professor and Head, Addiction Science Research and Education Center, College of Pharmacy, The University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 (E-mail: [email protected]).

Richard E. Wilcox, PhD, is Professor, College of Pharmacy, The University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 (E-mail: [email protected]).

SUMMARY. Neurobiology and molecular genetics are contributing heavily to a new understanding of the causes of chemical dependence (“addiction”). Willful chemical abuse is a problem that continues to produce significant societal costs including accidents, medical expenses, and family suffering. Pathological chemical dependence, on the other hand, is being recognized as a true medical disease that is also devastating, but in different ways. There is strong evidence in animals and humans that chemical dependence involves a dysregulation of the pleasure pathway (the “medial forebrain bundle”), located in the mesolimbic portion of the brain. Dopamine is one of the medial forebrain bundle’s major neurotransmitters. In this paper, we provide a research-based model for the causes of chemical dependence and its treatment, and integrate this information with classic Twelve Step treatment programs. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-342-9678. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2001 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Drug abuse, drug dependence, medial forebrain bundle, treatment, disease, addiction, neurotransmitters

Current Context of Addiction Research and Treatment

A significant misunderstanding has developed over the years regarding the causes of the “addictions” and what kinds of people develop addictions. Stigma, prejudice, and misunderstanding (“SPAM”) cause the uninformed to believe that addicts are bad, crazy, ignorant people who only need to get good, become sane, and become educated in order to get better. SPAM is the main reason why there are insufficient funds for treatment, prevention, education, and research on addictive diseases. Therefore, it is critical that health professionals understand (a) exactly what addiction is, (b) how addictions are produced, and (c) why treatments work. Once informed, health professionals should, in turn, take a proactive role in educating the general public about the true causes and nature of dependence, as an aid to reducing SPAM and the related suffering it causes.

Terminology

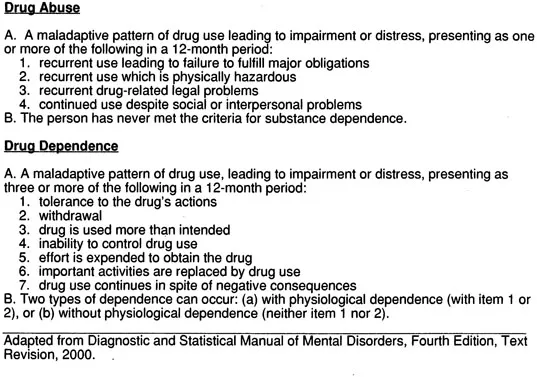

The DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, American Psychiatric Association, 2000) provides diagnostic criteria for differentiating between “substance abuse” and “substance dependence.” These are summarized in Table 1. The use of the term “substance” refers either to a chemical or to a drug. Using these criteria and other assessment tools, we can now clearly differentiate between drug abuse, involving a conscious choice, and drug dependence, in which the person has impaired control over behavior (Erickson, 1995). Thus, there are two different but related problems that must be dealt with in the so-called “drug problem” arena-abuse and dependence. Voluntary drug abuse is a major problem in the U.S., causing significant numbers of accidents, huge medical costs, lost productivity, and family abuse. In addition, alcohol and other drug abuse usually takes its toll in terms of physical problems of the drug abuser, such as liver cirrhosis or heart problems. Abuse may be reduced by making drugs harder to get (as in reducing the number of liquor stores in a particular geographical area), punishing the individual, and by education. Drug abuse usually does not require intense intervention and treatment.

TABLE 1 DSM Criteria for Drug Abuse and Dependence

Drug dependence, however, is still misunderstood. Many people, including some scientists, mistakenly believe that drug-induced euphoria (well-being), craving (drug-seeking), or physical withdrawal (hyperexcitability, tremors, seizures, etc.) are causative factors in chemical dependence. Even more often, people who simply use drugs too often or in high quantities are considered to be addicted. But the DSM-IV-TR criteria (Table 1) do not include amount or frequency of use as diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, note that only the first two criteria are physiological (tolerance and withdrawal), whereas the other criteria are psychosocial. The psychosocial criteria relate to “impaired control over drug use” or the inability to stop drug use under adverse consequences. Thus, it is possible to be dependent (“addicted”) without showing significant drug tolerance or dependence (seen as physical withdrawal). Conversely, people showing signs of withdrawal may not be addicted, unless they have two or more of the other criteria. This is important to point out because people often confuse withdrawal with “being addicted.”

It is helpful to think of drug dependence not as a “too much, too often” disease, but as an “I-can’t-stop” disease (Erickson, 1998). It is also useful to think of drug dependence as an “I-can’t-stop” disease because it is also a “brain chemistry disease” (Leshner, 1997). In fact, it is the dysregulation of the person’s brain chemistry that create the dependence, the impaired control over drug using behavior. The defining characteristic is whether a person can stop using drugs when a decision is made to stop or when a life-threatening drug-induced event occurs. This characteristic is also the one that is most often assessed through existing diagnostic methods. For example, an abuser who is faced with alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis will usually stop drinking, whereas an alcohol dependent individual (an “alcoholic”) cannot stop.

Proper understanding of these definitions allows better scientific study of the true causes of pathological drug dependence (a medical disease), as compared to willful drug abuse (a social problem). These definitions also reflect what we see clinically in patients with drug difficulties.

Neurobiology of Dependence

Genetics

Many recovering addicts report that they recall vividly the first time they took a drink or used cocaine. They realized with the first drug dose that they had a special connection with the drug. Other addicts remember that they could “take it or leave it” when they were first using, but after many drug exposures they could no longer stop. This concept of “impaired control over drug use” now represents the defining characteristic of chemical dependence (addiction).

The big question in addiction science concerns how “impaired control” occurs, especially the time-course of developing dependence and its causes via changes in brain chemistry. A great deal of research on the genetics of alcohol dependence (“alcoholism”) suggests that the tendency to become alcoholic is inherited (Cloninger, 1999). This tendency may arise as a result of altered gene functions leading to altered brain proteins. When genes are abnormal, brain enzymes and other proteins that are involved with neurotransmitter function may be abnormal. For example, the production (synthesis) or breakdown (metabolism) of dopamine is the responsibility of various enzymes. If the person has a genetic defect such that the enzymes that make or break down dopamine are faulty, then the amount of dopamine in the brain will be abnormal. Also, the response of that person’s brain dopamine systems to changes in the environment may be abnormal as well. In the mesolimbic system such abnormal functions of dopamine may lead to distorted mood, such as too little pleasure from positive experiences or too much pain from negative interactions. The person with such a genetic defect may be especially susceptible to the ability of cocaine to elevate brain dopamine to levels that are closer to “normal.”

Brain Chemistry

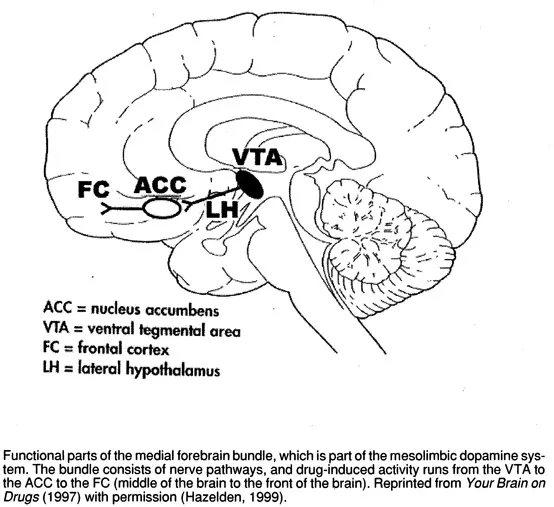

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain. Certain potentially addictive drugs match to specific neurotransmitters. For example, cocaine matches to dopamine because its major effect is to elevate brain dopamine levels. Heroin matches the brain’s natural morphine-like substances (the endorphins) because heroin mimics the effects of endorphins at their receptors. Ethanol (alcohol) is particularly troublesome because it seems to match well to several key neurotransmitters. Thus, alcohol has major effects on serotonin, GABA, glutamate, acetylcholine, dopamine, and the endorphins. Of course, nerve cells in the brain have many interconnections with other nerve cells. Thus, any brain pathway for something like pleasure will have contained in it different nerve cells that release dopamine, serotonin, endorphins, glutamate, GABA, acetylcholine, endorphins, and many more. This means that ultimately, many different addictive drugs may exert their effects through several neurotransmitter systems. For example, many scientists are proposing that there is a “final common pathway” for addictive drug effects on the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (cf. Koob et al., 1998). This pathway is also known as the medial forebrain bundle because it traverses the middle part of the base of the brain from cell bodies deep in the midbrain to innervate many structures within the frontal part of the brain (forebrain). Figure 1 illustrates these connections. What is important is that the dopamine pathway reaches a widespread portion of the brain that is concerned with emotion, pleasure, memory of emotional events, and decision-making ability for emotional events. In addition, different addictive drugs can “tap into” this dopamine pathway in several different ways. They may release dopamine, increase dopamine levels in the forebrain, or alter dopamine’s actions at receptor sites. Cocaine, for example, increases mesolimbic dopamine with a single administration. Repeated cocaine exposure can lead to adaptations in the user’s brain chemistry. This type of “emotional learning” represents an essentially permanent change in that person’s brain wiring. Under these conditions, relative “normality” of dopamine activity and of the functions of the medial forebrain bundle are achieved only in the presence of cocaine.

Sensitization

We can reasonably assume that addicts who become dependent early in life and/or with little drug exposure are the most heavily genetically predisposed to

FIGURE 1. The Medial Forebrain Bundle

the disease. These individuals may have more severe defects in one gene, perhaps having little ability to produce normal amounts of brain dopamine. Alternatively, these persons may have more modest genetic defects in several genes. Here, the person may produce abnormally low amounts of dopamine but also break down dopamine too efficiently. Together, this would lead to severe reductions in brain dopamine levels. For these people, a single exposure to cocaine may be life-changing because of cocaine’s ability to dramatically increase levels of dopamine. This occurs because dopamine is normally removed from its receptors and “recaptured” by the releasing nerve cell through a reuptake process. Cocaine blocks this process. Thus, once dopamine is released upon nerve stimulation, its levels continue to grow in the space between nerve cells (the synaptic cleft). For people in whom genetic deficits of dopamine have led to difficulty in experiencing normal emotion, that first cocaine “high” may be the first time that they have ever had high dopamine levels (“felt normal”).

Other addicts require months or years of drug use before they acquire “impaired control.” It would appear that these people may have more subtle genetic defects and that a combination of factors, including exposure to the addictive agent, act in concert to activate the medial forebrain bundle. During this time, there are a variety of adaptations produced in the user’s brain chemistry by the drug. For cocaine, changes in many aspects of dopamine activity can occur with repeated cocaine exposure. These include changes in transmitter production, release, interactions with receptors, return to the nerve cell, and breakdown. These changes represent the brain’s attempt to adapt to the novelty of experiencing high dopamine levels. One particularly intriguing hypothesis is that nerve cells in the medial forebrain bundle that transmit the pleasurable and “craving” qualities of drugs may be “up-regulated” with chronic drug exposure. This increase in activity is termed sensitization (Robinson & Berridge, 1993). These pathways become more active in the drug’s presence and even more active with repeated drug exposure.

However, there is a “cost” for these adaptations. The cocaine “high” is followed by a post-cocaine “low.” In fact, levels of brain dopamine appear to be even lower than the person’s original baseline for a period of time after the cocaine wears off. Since the cocaine “high” may be increased with repeated exposure as a result of sensitization, the cocaine “low” may also be bigger (i.e., a larger drop in dopamine occurs). While some investigators consider this to be an “acute withdrawal,” it is more properly defined as an immediate rebound in which the brain attempts to return total dopamine levels over time to the original set-point for that person. Thus, drug exposure in these at-risk individuals establishes a molecular memory of the drug-taking. In particular, an enhanced (sensitized) “demand or urge” for the drug may be responsible for turning on the addictive process in these users’ brains (Robinson & Berridge, 1993). Consistent with this idea, addicts often report that they “need” drugs-meaning that their body demands or requires the drug to function normally, in a manner similar to.the body’s need for food, water, and air. This makes sense when we understand that the medial forebrain bundle passes through the hypothalamus-a structure containing critical regulation centers such as those for eating, drinking, and breathing.

Emotional Learning

The model presented above is the “medial forebrain bundle model of impaired control” which focuses on a portion of the limbic system. Other recent work (Koob et al., 1998) has implicated the extended amygdala, a brain system that includes those areas discussed above and also the amygdala. In this view, the amygdala regulates emotional memory, and registers the significance of prior drug use. Thus, in the case of the cocaine dependent person, in addition to becoming sensitized to cocaine (having progressively larger amounts of dopamine in the areas reached by the medial forebrain bundle), the individual “learns” that cocaine fulfills a need. The extended amygdala may play either a major or an ancillary role in the production of chemical dependence. More research is necessary to clarify exactly which brain areas are involved and how they interact in the genesis and development of chemical dependence.

Non-Drug Therapies

The traditional recovery program for drug dependence is the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Author The Editors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Articles

- Special Topics

- Index