- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

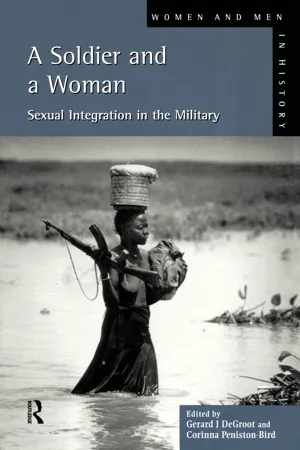

A Soldier and a Woman

About this book

The question of women's role in the military is extremely topical. A Woman and a Soldier covers the experiences of women in the military from the late mediaeval period to the present day. Written in two volumes this comprehensive guide covers a wide range of wars: The Thirty Years War, the French and Indian Wars in Northern America, the Anglo-Boer War, the First and Second World Wars, the Long March in China, and the Vietnam War. There are also thematic chapters, including studies of terrorism and contemporary military service. Taking a multidisciplinary approach: historical, anthropological, and cultural, the book shows the variety of arguments used to support or deny women's military service and the combat taboo. In the process the book challenges preconceived notions about women's integration in the military and builds a picture of the ideological and practical issues surrounding women soldiers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Soldier and a Woman by Gerard J.De Groot,C Peniston-Bird in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Sexual Integration in the Military before 1945

Introduction

Arms and the Woman

GERARD J. DEGROOT

During the First World War, the British poet Nora Bomford expressed her frustration at being unable to fight for her country:

Sex, nothing more, constituent no greater

Than those which make an eyebrow's slant or fall,

In origin, sheer accident, which, later,

Decides the biggest differences of all.

And, through a war, involves the chance of death

Against a life of physical normality -

So dreadfully safe! O, damn the shibboleth

Of sex! God knows we've equal personality.

Why should men face the dark while women stay

To live and laugh and meet the sun each day.1

Than those which make an eyebrow's slant or fall,

In origin, sheer accident, which, later,

Decides the biggest differences of all.

And, through a war, involves the chance of death

Against a life of physical normality -

So dreadfully safe! O, damn the shibboleth

Of sex! God knows we've equal personality.

Why should men face the dark while women stay

To live and laugh and meet the sun each day.1

The Bomford poem expresses a number of themes central to this book. It is not an overtly feminist statement, though some feminists find her sentiments admirable. Rather, Bomford's desire to fight arises out of her love of country and her feeling of injustice at the fact that men should suffer war's horrors while women remain the protected ones. She also seems fully confident of the ability of women to fight, sensing that the obstacles to their participation in combat are arbitrarily determined gender distinctions — the shibboleth of sex. This book is about women who attempted to defy those distinctions, in the process challenging the essentially masculine nature of war. It is about revolution, but also counter-revolution - the way societies have contained the threat posed by women's participation in the military and how gender norms are powerfully reasserted when peace returns.

Since the early 1970s, military service, and particularly participation in combat, has been seen by some feminists as one of the most important bastions of patriarchy. To knock it down, it seems, would leave the entire edifice of male domination fatally weakened. These 'right to fight' feminists have challenged governments and the military establishment to allow women into areas of combat from which they have heretofore been excluded. But for most feminists the issue is symbolic; few actually aspire to drive a tank or fire a machine gun in anger. Thus, the real battles have been fought by proxies: women who want to serve because they love their country or because they are attracted by the thrill of landing a fighter on an aircraft carrier in choppy seas. In fact, those women who want to fight very seldom express their demands in feminist terms or seek overtly to advance the cause of women. This is partly because the naturally conservative military is not a very comfortable home for a woman keen to rebel against social conventions. The woman who aspires to an active military career often wants only to change a few of the rules regarding where and in what capacity she herself might serve. She otherwise supports the military's role as a guardian of tradition. She wants to fight because she is proud of and seeks to preserve the society in which she lives.

As the chapters in this book demonstrate, those women who served in the military before 1945 did so for sublime patriotic reasons. They might have been empowered as a result of this service and made more aware of the injustices of patriarchy, but that was not the motivation for service in the first place. For instance, as Christopher Schmitz shows, British women who volunteered for service as nurses during the Boer War were very often members of suffrage societies, but their motivation for going was to relieve the suffering of soldiers and to play their small part in the defence of the British Empire. The benefit which their service brought to the cause of votes for women was incidental. Likewise, those who joined the 1st Russian Women's Battalion of Death during the First World War, as Laurie Stoff shows in her chapter, did so for overtly conservative purposes, namely because they wanted to win the war and preserve the political status quo. They opposed the Bolsheviks, even though, if propaganda was to be believed, the Bolsheviks offered the better hope for women's emancipation. One is reminded of the response the militant suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst gave to critics who questioned her willingness to serve the 'oppressive' British state after war broke out in 1914: 'What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in?'2 The story is the same in almost every chapter of this book: women are motivated by deeply patriotic feelings but are often frustrated in their attempts to express their patriotism actively.

Service is sometimes seen as a way to achieve female empowerment, not through demonstrating the contribution women can make, but rather because the cause itself seems to offer the best hope for women. As Helen Young reveals in her chapter, Chinese women were motivated to participate in the Long March because of a desire to play a part in the Communist revolution, but also because Communism seemed to offer a better life for women.

This is significant because women have not traditionally been given an opportunity - through political or military service - to demonstrate their patriotism or devotion to a cause, and as a result have not been seen as real patriots. Lacking the opportunity to demonstrate their citizenship, they have been unable to prove that they are fully fledged citizens, deserving of the basic rights automatically accorded men. The testimony of women who served in the auxiliary forces in Britain during the Second World War reveals a deep sense of pride (not to mention delight) at being given the opportunity to bear the burdens of citizenship. Through service, a sense of belonging emerged. This process of realizing national identity is perhaps most evident amongst women (because they have seldom been given the opportunity to serve), but not peculiar to them. What the women felt was, for instance, hardly different from the emotions of British working-class males in the First World War, who flooded to recruiting offices when the Secretary of State for War, Herbert Kitchener, pointed at them from posters and told them they were needed. Never before had anyone in high authority expressed a need for them.

It is only by understanding the sense of importance felt by heretofore marginalized groups during wartime that one can understand the frustration felt when participation was denied. As Penny Summerfield demonstrates, the disappointment felt by women who wanted to join the Home Guard in Britain in the Second World War was deep because the very existence of the Home Guard seemed to demonstrate that the need was urgent. Men deemed unfit for regular military service (or those in reserved occupations) were being organized into local defence units because the threat of German invasion seemed real. The very fact that old or infirm males were granted such a symbolically important role made the denial of this expression of citizenship to able-bodied women seem all the more galling. The women concerned wondered why the preservation of certain gender roles seemed more important to the government than national survival.

Women who aspired to join the Home Guard argued that their membership was perfectly compatible with 'women's traditional role as guardian of the home'.3 This was a powerful argument, as it played upon a culturally acceptable form of female violence common to many societies. For instance, in Vietnamese society, an ancient proverb holds that 'When pirates enter the home, even the women must fight'. At various times, in order to secure the services of women, Vietnamese nationalists defined the home in broad terms as the nation. But in Britain during the Second World War the argument — as it applied to membership in the Home Guard - was either rejected or simply ignored by the government. Nevertheless, at exactly the same time, the idea that women should defend their homes was used to justify their participation in the auxiliary forces, particularly when this participation came perilously close to actual combat. For instance, the disruption to gender roles which the mixed-sex anti-aircraft batteries represented was cushioned somewhat by frequent reference to the idea that the women were protecting their homes from a very visible German invader. The theme arose again when the government proposed that some auxiliaries (including some gunners) might be sent to the continent after June 1944. Critics objected that this deployment would transform the women from defenders to invaders. 'Any woman will defend her home', the Labour MP Mrs A. Hardie argued, 'but it is very different when you send her away to other countries. ... It is a nice new world that some . . . picture for the rising generation of women, who now not only have to produce innumerable children but fight wars as well.'4

For many women, service to the cause was often an extension of what were seen as natural womanly duties. At the heart of the separate spheres argument was the contention that men and women each had unique talents which predetermined their social roles. Thus, Frederick Treves, surgeon to Queen Victoria and Edward VII, who favoured the employment of women in the Boer War, argued that 'the perfect nurse ... is versed in the elaborate ritual of her art, she has tact and sound judgement, she can give strength to the weak . . . and she is possessed of those exquisite, intangible, most human sympathies which, in the fullest degree, belong alone to her sex'.5 Those pressing for women's involvement in war argued that these uniquely female talents had application in a theatre of war. Mabel Stobart, who formed the Women's National Service League in Britain after the declaration of war in 1914, did so with the goal of'forming Women's Units to do women's work of relieving the suffering of sick and wounded'.6 It is interesting that Stobart came to her decision immediately following a peace demonstration in which she felt moved to take part. When, during the course of the demonstration, news of the declaration of war reached her, she immediately began to think about the contribution she could make to the war effort. She considered it her womanly duty to campaign against war while peace still seemed possible and to relieve the suffering of war once it emerged that a conflict was inevitable.

As the chapters in this book demonstrate, the qualities Stobart had in mind had wide application. British women who volunteered as nurses during the South African War were needed because the male nurses had so obviously proved incompetent, thus causing the sick and wounded to suffer unnecessarily. Likewise, women were needed on the Long March because they were especially well-suited to the liaison and propaganda tasks essential to that particular campaign. For the march to succeed, it was necessary to obtain the cooperation of the population in the areas through which the force travelled. Because women seemed less threatening than men, they found it easier to obtain the trust of the locals. Their apparently benign countenance rendered women particularly well-suited to insurgency campaigns. As Margaret Collins Weitz demonstrates in her chapter on the French Resistance, women made effective spies and assassins for the very reason that they were not expected to play such a role. But what was galling to those women eager to perform 'women's work' was that skills so self-evident often went unrecognized by male leaders. The qualities which made women valuable to a cause — namely their nurturing nature or innocent inconspicuousness - also impeded their recognition by the cause. Because war is brutal, those who appeared ingenuous and unthreatening seemed inappropriate to the struggle. In South Africa, China and France, women had first to convince male authorities that they were qualified for 'womanly' roles.

The participation of women in the military and in war is nothing new. While formal auxiliary units composed of women are largely a twentiethcentury phenomenon, women have been performing auxiliary functions throughout the history of warfare. As Brian Crim has discovered in his investigation of women's role in warfare in early modern Europe, armies often depended upon women to perform these functions without which military campaigns could not succeed. The camp follower, heretofore seen as a parasite on the military body, was in fact an essential component in the logistical chain. Poorly paid soldiers, who could not afford to leave their wives and children behind when they went on campaign, took their families with them. In 1776, the Berlin garrison of Frederick the Great consisted of 17,056 men, 5,526 women and 6,622 children. Since these women and children lived in the camps or barracks with the soldiers, they were directly subjected to, a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Sexual Integration in the Military before 1945

- Part 2: Sexual Integration in the Military since 1945

- Notes on Contributors

- Guide to Further Reading

- Index