![]() Part I:

Part I:

We Come to Tell Our Story![]()

Chapter 1

A Conversation in Ordinary Time

On a hot and humid Sunday, the Gospel reading focused on wheat and chaff. I had been forewarned about the Gospel because the Lutheran church near my home had posted the sermon title "Dealing with Weeds." The guest homilist at our small Catholic church read from the text for the thirteenth Sunday in ordinary time, Matthew 13:23-44. Like our Lutheran neighbors, we were having a go at it, including the metaphor of weeds. At the end of the homily the community was invited to step to microphones located around the worship space and offer a comment or two. As members fanned themselves with bulletins and worship aids and mopped brows wet from the oppressive humidity, a few folks stood and made comments. Most talked about the recent rains and their effects on gardens. One woman talked about a volunteer experience where she found herself planting native wildflowers and vegetation a scant week after pulling similar plants from her own garden. Finally, an active member of our community—a woman sober for twenty-four years—stepped to the microphone and offered a bit of translation. Her comments went something like this: "I am a member of Alcoholics Anonymous. We refer to our 'chaff or 'weeds' as character defects. In the sixth step of Alcoholics Anonymous we become ready to have God remove these defects of character. And in the seventh step we humbly ask God to remove our shortcomings. I have found in my years of sobriety that it is best to leave to God what is removed and what is left to bloom." "Ah," said the collective community and we moved on to the prayers of the faithful....

The Power of Stories

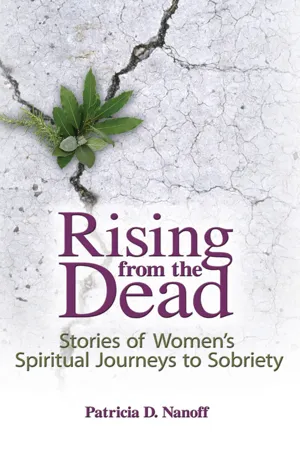

This book is about alcoholic women. It documents the spiritual life stories of women who became sober at a time when being an alcoholic woman placed one so far beyond the pale that she was considered to be literally beyond redemption. The women who volunteered their stories for this book did so in the hope that women who still suffer might find some solace in their shared stories, and in the hope that pastors, pastoral counselors, and chaplains in the Christian community might learn something about walking the territory of fallenness so familiar to these women. Among us are anonymous women who entered the tunnel that leads to hell and yet found their way back. They are often seen as the weeds and chaff of our communities; however, their stories reveal the powerful reconciling presence of God. This book documents their stories and their unique way of telling stories. There is an unnecessary disconnect between the redemption stories found in the recovering community and the faith communities where many of the dramas play out. This is a love story. I found great integrity and strength in these wonderful elders; theirs is a generosity of spirit that is compelling. The path they have traveled and the spirituality they practice is not for everyone—this book is not an apology for Alcoholics Anonymous. The goal of this book is to map the territory between the individual shattered life and the Christian faith communities where reconciliation might take place, between the vibrant spirituality of the twelve steps and helping professionals who have not yet learned to speak that language.

This book came about, in part, because of my own story. My story is an ordinary one. I grew up in an alcoholic family and I began my own personal spiritual journey of reconciliation in the spring of 1973. This experience has been a blessing beyond words and is noteworthy because telling one's own story is a departure from commonly held "best practices" for pastoral care, counseling, and health care. Current expectations require the helping professional to submerge the personal in order to hear the story being offered, yet the field of alcoholism has long practiced counseling strategies that require something quite different, that is, that the story of the counselor is not only relevant but necessary to the therapeutic relationship. My own story matters, counts, when engaging in relationship with those I counsel.

A belief in the power and relevance of one's own story can be viewed as one kind of feminist theological practice. In fact, theologians practicing womanist theology highlight the power and deep significance of personal story. Theologian Delores S. Williams begins her powerful book Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk by inviting theologians to tell some part of their own stories as one way of locating their theological work.1 Williams defines womanist theology as a kind of "prophetic voice" theology that is concerned with justice issues within the African-American community.2 For Williams and others practicing feminist and womanist theology, one's own story and the stories of others provide a context or framework for more abstract principles such as salvation and reconciliation—indeed, womanist theology reminds us that the most powerful theological principles are expressed within the context of story. Stories are the carriers, the containers for our most sacred and powerful understandings of the self and of God.

How is this relevant to the discussion at hand? For alcoholic women, context is everything. The matrix of shame and remorse that binds the suffering alcoholic is in fact the very matrix that can provide relief, reconciliation, and redemption. The situations and choices that have caused harm, made her feel ashamed and diminished become the vehicle for God's grace and reconciling action. The very choices that lead to an intrapsychic break become the means for reconnection, and ultimately, the vehicle through which others are healed and reconciled as well. The experience of active alcoholism is exactly like descending into hell. The women who suffer with addiction are almost never living life in ordinary time—their pain and suffering moves them to another more terrifying and extraordinary place. Only entry into God's own sacred space can reclaim them. This book is a guide for the helping professional who wants to understand that particular pathway from hell to redemption.

I will focus exclusively on the stories of recovering women because their stories tend not to be told. Women's stories are under-represented in the literature on addiction therapy and their experience is often misunderstood or misrepresented. While conducting the initial research for this project it became painfully clear that little is written about women with long-term sobriety and they face psychological discrimination when they reveal their recovery in public spaces. It is not necessary to detail what the greater society thinks of alcoholic women. To be an alcoholic woman is to stand accused by society in the most shameful way. This attitude is pervasive and often toxic for women as they seek treatment and recovery, yet the stories offered by the women I interviewed trace a path through such treacherous territory.

Who are the storytellers? The women whose stories are represented here were identified through my contacts within the community of Alcoholics Anonymous and by word of mouth. Those who participated had achieved lengths of sobriety ranging from twenty-five to fifty-three years. They originated from various regions of the United States including Minnesota, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and Pennsylvania. Their ages ranged from forty-six to ninety years old. All of the interviews were conducted in person. The participants were asked to tell their life stories following a formula frequently used in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings worldwide: tell how it was, what happened, and how it is now.3 I used this familiar formula as a means of understanding and documenting what these women with long-term sobriety "know" and how they have come to know it. Amazingly, when approached none of the participants asked me for identification or any proof of professional credentials. Rather, they identified my credibility and trustworthiness via my connection to those they knew in the recovery community. Any expertise I might have as a clinical social worker or as a theologian was seen, at best, as secondary to my knowledge and understanding of the language and practice of recovery. Had I not been a fluent speaker of the recovery language these particular stories would not have been offered. During the interviews I became aware of the "hidden" quality of the stories; theirs is a powerful presence that operates below radar.

A deep and uncharted ocean of stories is held by the community of recovering alcoholics. These stories are transmitted by word of mouth and, although audiotapes are circulated that feature well-known speakers at conventions, stories such as the ones contained here are not part of any documented record. These stories live by breath alone, transmitted through the sighs and silences at AA meetings. I decided to record these stories as a way of capturing a small bit of the fire and light that they provide and I am painfully aware that in documenting them something essential has been lost. In my time with the long-sober women of AA I learned that in hearing the spoken stories and the silences between them, the real spirit of the story is revealed. These stories offer a dynamic model of life-reclamation that is of significance for pastoral ministers in their work with women who suffer from alcoholism.

I want to acknowledge also that this book relies a great deal on the language of twelve-step recovery. If this language is new to you, some of the references could be a bit puzzling. Some basic details may be helpful. AA offers the following self-description:

We are not an organization in the conventional sense of the word. There are no fees or dues whatsoever. The only requirement for membership is an honest desire to stop drinking. We are not allied with any particular faith, sect or denomination, nor do we oppose anyone. We simply wish to be helpful to those who are afflicted.4

Members of AA follow a program of recovery based on the twelve steps and twelve traditions that are detailed in the foundational book Alcoholics Anonymous, referred to by members as the "Big Book" and in the companion book Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, referred to by members as the "twelve-by-twelve."5

From Ordinary to Extraordinary

The stories documented in the pages that follow offer one model— to call on language suggested by Rebecca Chopp—of storycrafting as salvage, as saving work.6 The process of storycrafting discussed in the chapters that follow provides an amazing map that has great value for those practicing pastoral care, counseling, and for anyone working to strengthen a community of faith. The women who agreed to tell their stories for this book are living out their lives in the place where ordinary time and sacred time meet. This is part of what makes their stories so compelling. Their lives embody one type of sacred reality that lives within ordinary time; theirs is the extraordinary revealed within the ordinary. While I expected to hear good and entertaining stories when I began research for this book, I was unprepared for the thunderous, spirit-filled nature of these narratives. The very fact that these lives are considered by their owners to be "commonplace" has changed my understanding of the activity of God's spirit in the world.

What is the difference between ordinary time and sacred time as experienced by the women of this study? How does time become transformed? We live much of our lives in ordinary time. This means that our lives take on a shape that is familiar and routine. We may experience highs and lows, but they are mundane and in many ways predictable. These ordinary times are interrupted by birthdays and holidays, but even the interruptions have a familiar form and function in our lives. However, some ordinary experiences interrupt ordinary time in fresh and new ways, transforming ordinary time into extraordinary time. We know intuitively that birth is an ordinary occurrence; in the time it took me to write this sentence many new souls were welcomed by families. These events are noteworthy because they are both ordinary and extraordinary—we could say that they are "ordinary" in the abstract and "extraordinary" in the particular. If it is my child that is born the experience is anything but ordinary! The same dynamic is operating when someone dies; death is ordinary until it is the death of someone I know and love.

The experience of transformed time is of particular interest when considering alcoholism and its consequences for those who love the alcoholic. In the alcoholic family, ordinary times become twisted into extraordinarily difficult times and family members find themselves yearning for the peace of the mundane; however, this is not the only instance where ordinary time becomes transformed. As I have begun to share what I learned while researching this book, I have been reminded how true this experience rings for people living with other life-changing situations and events. Death of a loved one, divorce, protracted or terminal illness, all hold the capacity to shift us from ordinary to extraordinary time. This is one of the gifts of the stories given for this book—a grace is revealed when we navigate this territory.

In the chapters that follow we will trace the path from ordinary to extraordinary, and in doing so perhaps capture some small sense of the breath of God moving within the ordinary and transforming it into the sacred extraordinary. The shape of this book is meant to mirror the process encountered in the Christian liturgical year with a special focus on Lent, the time between Ash Wednesday and Pentecost. We will follow the move from ordinary time to sacred time, mirroring the liturgical journey that is so integral to Christian life and tradition. We began with a brief conversation in ordinary time. The chapters that follow consider life narratives within the liturgical framework described in the lyrics from "Song of the Body of Christ"

We come to tell our story.

We come to break the bread.

We come to know our rising from the dead.7

In Chapter 1, the women tell their stories as they would in AA meetings and no interpreting theory is brought to bear on the narratives as they have been offered. In Chapters 2 and 3, the same narratives are broken open and the inner workings are considered within the context of more secular models of alcoholism treatment. In Chapters 4 through 8, the narratives are considered in relationship to theological categories and models. Chapter 9 discusses barriers specific to helping professionals and pastoral counselors. Chapter 10 considers specific suggestions for the use of story in pastoral ministry and specific tools and strategies for pastoral counseling are detailed. In this way then, liturgical time serves as the container or frame for the examination of the process of story crafting as the genesis of one kind of sacramental encounter.

![]()

Chapter 2

Entering Sacred Space

Storycrafting

What is the purpose of narrative construction in the recovery process? Plainly spoken, what is story for? NH posed this question to me when she agreed to tell me her story. It was her concern that her story have some utility, that it be for someone, that there be a person who needs to hear what she has to say. During a telephone conversation she explained to me that when she tells her story at AA meetings she is certain that God will lead her to say whatever is needed for the person who needs to hear her story. Before she would agree to tell her story for this book she needed to think about whether there might be someone who needed to hear something from God, and she believed firmly that this "something" would be expressed within her life experiences. This criterion had to be satisfied before NH agreed to speak to me; without it her story would be meaningless, or worse, an exercise in pure ego. I note this detail because it is essential to the approach of storytelling found in AA. And although this formula for narrative construction is not stated explicitly in AA literature, except in one or two places, it is so much a part of the expectations of those in AA that it was assumed by all who participated. Consider the uniqueness of this approach to storytelling: God will use my story to communicate to you. My story participates in the active reconciling grace of God in the world.

Story is the central element of the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous. The sociological impact of AA and related movements is undeniable and well documented.1 Members of AA operate within a subculture with recognizable language, customs, and rituals. Many of the key features of the program are so familiar and common in U.S. culture that they have achieved the level of cliche as evidenced by bumper stickers reading "Easy Does It" and "Honk if you are a friend of Bill W." AA meetings often begin with a story, that is, a speaker tells her story and subsequent discussion focuses on ideas that the story contained. AA stories are told in a formulaic way and it is common to hear members assert that God speaks through the storyteller, thus the storyteller is of no consequence. Story is seen as a vehicle— what holds the transcendent meaning. Trans...