![]()

1

Iron Smelting and Smithing

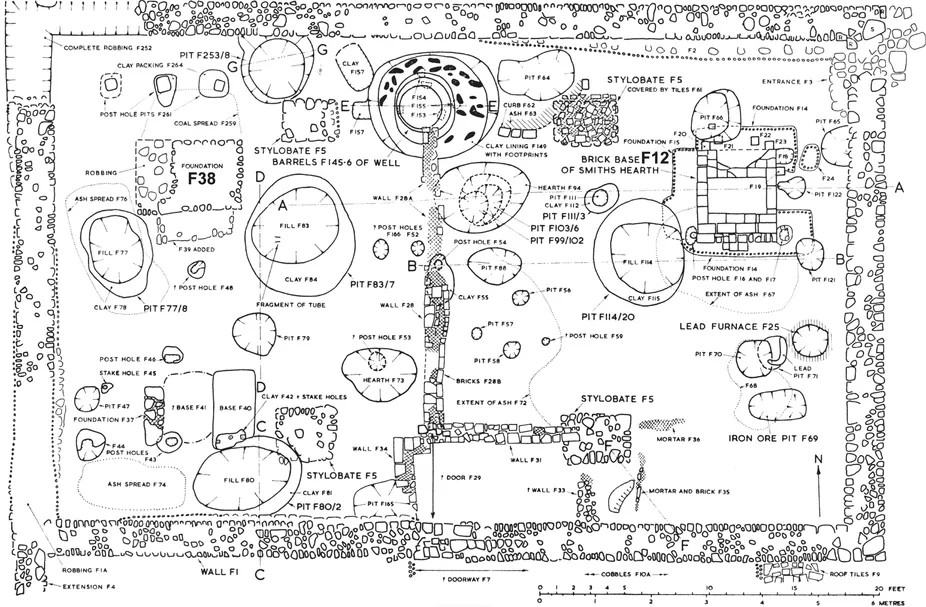

FIGURE 1.1

Forge at Waltham Abbey, Essex (after Huggins and Huggins 1973, fig 2)

Iron ore deposits are widespread in Britain, the main types being carbonate, haematite and limonite whose incidence is discussed by Tylecote (1962, 175–179). Quarrying with trenches as well as tunnelling is known from the Forest of Dean (Schubert 1957, 123, pls XIII-XIV) but widely occurring bell-pits are more frequent evidence of medieval deep mining of iron ore (Tylecote 1962, 284–285; Beresford and St Joseph 1979, 256, fig 107). Bell-pits near Sedgeley, West Midlands, had 1.5m diameter openings, a depth of 4.6m to 6.1m, and a maximum diameter of 3.6m.

1.1 Iron Smelting

Archaeological evidence for iron smelting is considerable and is discussed elsewhere (Tylecote 1962; 1976; Schubert 1957; Crossley 1981). A brief outline of the process is given here.

Iron ore was frequently roasted before smelting in a bloomery or blast furnace to make it more porous and more easily reduced. Medieval bloomery furnaces are of two basic types, the horizontally developed and the vertically developed bowl furnace, each with slag-tapping facilities. In use a charge of ore and charcoal was placed in the furnace and during smelting some of the lighter impurities were tapped off as slag until at the end cinders, slag and a bloom of iron were left at the bottom. The extracted bloom was consolidated on a string hearth by repeated hammering and with intermittent re-heating, the attached cinders being removed and the entrapped slag driven out to produce a bloom of wrought iron. This was then cut into pieces and if necessary rendered into bar iron for the blacksmith. Towards the close of the medieval period the blast furnace, which produced liquid iron in addition to slag, was developed. The first blast furnace definitely known to be in existence in Britain was at Newbridge, Sussex, in 1496 (Tylecote 1962, 301).

Iron smelting and smithing produce many waste products, not all unique to a single stage, and interpretations drawn from them, particularly where they are found without structural association, should be based on scientific examination. The products of smelting include the raw bloom with its entrapped slag and attached cinders, furnace bottoms, slag and tap slag, whilst smithing of the raw bloom produces slag hammered out of the bloom and hammer scale formed on its outer surface. The final forging also produces hammer scale and fine, almost microscopic, drops of slag.

1.2 Iron Smithing

Blacksmith’s forges or smithies are known from a number of excavated sites, and include the 13th-century bloomery and adjacent smithy at Godmanchester in Cambridgeshire (Webster and Cherry 1975, 260, fig 96), where one room of a two-room building was used as a smithy and remains of four contemporary iron-smelting furnaces were found in a building to the rear. Medieval documents indicate that string hearths were sometimes attached to bloomeries (Salzman 1967, 31; Tylecote 1962, 287–289) and were sometimes separate (Schubert 1957, 126–127), and it is at present unclear whether this smithy housed a string hearth or was a conventional smithy.

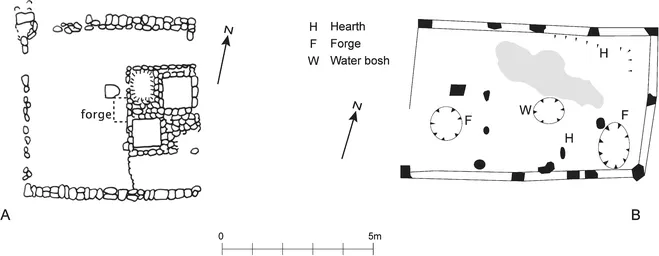

At Waltham Abbey, Essex, a forge built about 1200 on the home farm of the Augustinian Abbey survived the Dissolution and stood, not necessarily in use, into the 17th century (Huggins and Huggins 1973). Iron ore and bloomery products indicate that the site, if not the building, was used for iron smelting. The forge (Figure 1.1), built as a three-bay aisled building 15.7m by 10.1m, was certainly used for making complete objects since bar iron, incomplete forgings and a series of tools (catalogued below) were found, as well as two smith’s hearths surrounded by concentrations of hammer scale. One hearth (F12) consists of a rectangular brick base, 1.67m by 1.42m surviving five courses high and set on a wider foundation; the other hearth (F38) survives only as a flint and chalk foundation, 1.9m by 1.4m. Both have separate foundations which could have supported a water bosh. The more complete hearth is very similar to that in a smithy of c1395–1405 at Alsted, Surrey (k etteringham 1976, 25–29, figs 19–21), where the 6.0m by 5.5m building (Figure 1.2A) had a rectangular stone hearth with fire-pit, working surface and space for bellows, as well as a large sandstone block immediately in front to support the anvil block. Hammer scale was found on the floor surrounding the stone and along the front of the hearth, and the site produced a number of tools which may be related either to the smithy or to earlier iron smelting.

FIGURE 1.2

A: Smithy at Alsted, Surrey (after Ketteringham 1976, fig 19). B: Smithy at Goltho, Lincolnshire (after Beresford 1975, fig 22)

The late 14th to early 15th-century smithy at Goltho, Linconshire (Beresford 1975, 46, figs 21–22), a timber building 8.0m by 5.0m (Figure 1.2B) surrounded by a yard surfaced with smithing slag, had two pits which produced smithing furnace bottoms (Tylecote 1975). The later pit, to the SE, was used until the time of desertion. A clay-lined pit in the floor may have been a water bosh or cooling water-basin, but no blacksmith’s hearth similar to those at Waltham Abbey or Alsted was found. A small quantity of bar iron, and a few tools and other objects do, however, indicate the forging of objects.

Blacksmiths frequently also acted as farriers, and the late 14th to mid 15th-century smithy at Huish, Wiltshire, was evidently used by a farrier (Thompson 1972, 115, fig 1). The building, which was destroyed by fire, was 3.0m by 2.4m and had two hearths, in one of which were two horseshoes, a claw hammer, a poker and other indeterminate objects. The forge at Waltham Abbey produced evidence connected with farriery in the form of four horseshoes, two oxshoes and 160 horseshoe nails (Huggins and Huggins 1973).

The smithies already noted are mainly on monastic, manorial or village sites, but excavation in Southampton, Hampshire, located part of the floor of a late 12th or early 13th-century urban smithy floor (Platt and Coleman-Smith 1975, I, 238, 267, 349, pl 74).

The smithy must have been an important building during the construction and occupation of castles, and several have produced relevant finds. Iron slag, bar iron, tongs, a sledgehammer, chisel and axe from Deganwy Castle, Gwynedd, are probably from a smithy. They were found together at a depth of 61mm in an isolated hole in the bailey of Henry III’s castle, begun 1245 and destroyed 1263, but could be of earlier date since the site had been in intermittent occupation for many centuries (Alcock 1967). Ironworking, probably initially including the smelting of ore, was the main activity in a workshop on the motte at l ismahon, Co. Down (Waterman 1959a, 152, 155–156) during the 13th and 14th centuries, and hammer scale and forging hearth slag were found with scrap iron and bronze on the site of a 14th-century workshop at Bramber Castle, West Sussex (Barton and Holden 1977, 38, 66–67). West of the gatehouse-keep sundry nails, horseshoes, etc, were found in a probable 14th-century context with very little slag and may imply a second smithing area (Barton and Holden 1977, 67; ex inf E W Holden).

Less certain evidence comes from Lyveden, Northamptonshire, where a roughly rectangular paved area 6.5m by 4.2m with areas of burnt clay and stone, charcoal, iron slag and coal has been interpreted as a probable smithy in use c1200–1350 (Steane and Bryant 1975, 4–9, 21–22, figs 7–8).

At Walsall, West Midlands, a 4.0m by 11.0m building of 13th or 14th century date may have served as a forge and later as a fuel store (Wrathmell and Wrathmell 1974-75, 27–29, 51, figs 2–4, pl II).

1.3 Bar Iron and Incomplete Forgings

The blacksmith’s raw material, other than scrap iron collected for reuse, comprised pieces of iron cut from blooms and lengths of bar iron of varying size and cross section. Purchases of iron for use in medieval building-work are often mentioned in accounts (Salzman 1967, 286–288), and the iron was both native and foreign, the former including specifically named Weardale, Gloucester and Wealden iron, and the latter particularly Spanish iron. The iron is often priced and bought by the stone or hundredweight, or in sizes called gad, seam and hes. It was sometimes just held in store, but was also bought for particular use, such as Spanish iron for window bars bought at Corfe in 1292, or for hooks and bands at Dover in 1363. Steel, often from Sweden, was also bought for tool and knife edges (Salzman 1967, 288).

A shaped, rectangular sectioned bar from Winchester (A1) proved on examination to be a dense, well-worked piece of wrought iron with few slag inclusions. A bar fragment (A2) from Deganwy Castle found with other blacksmith’s equipment and iron slag, has a chisel-cut end, indicating that it is part of a once larger piece. The shape of the chisel-cut shows the characteristic way the blacksmith cut metal, since it was important not to cut entirely through the iron and dull the edge of the chisel on the hard face of the anvil. In practice the smith reduced the force of the hammer blows on the chisel just before the cut was complete, and then often broke it by hand.

Two pieces of iron (A3–A4) are known from a site with ironworking evidence at Newbury, Berkshire, but over 100 pieces of sheet iron, bar iron of square, rectangular and round section, and lengths of iron wire come from the forge at Waltham Abbey. A5–A10 are a representative selection, whilst A11–A15 are shaped pieces, some perhaps scrap iron or partly forged objects. Definitely identified incompletely forged objects from the site, catalogued below, include those of six auger bits and a key, but it is impossi...