![]()

1

The opportunity of corporate responsibility

Climate change and poverty are real problems and these problems are especially difficult in the ‘hard’ industries such as mining, oil, textiles and travel, for which solutions to social and environmental problems are not readily available or simple to implement. There is a growing political and social consensus that businesses, especially multinational corporations (MNCs), need to accept their share of responsibility for these problems. Yet too often companies are criticised for their role in causing these problems, without acknowledgement of the positive contributions companies make to the communities and environments in which they work. This book highlights the ways in which companies can create ‘shared value’. This approach means that companies take corporate social responsibility (CSR) seriously, while seeing the opportunities that exist for growing their business, brands and markets by engaging in this challenge. Thus CSR is about enhancing profitability and building the company’s brand; seeing CSR as an opportunity not a threat. CSR is not philanthropy; instead it is about companies ensuring that their core operations contribute to social development and environmental protection as well as expanding the business and growing profits.

The case for CSR is strong and businesses today are keen to engage in the social and environmental issues of our time. But what is often lacking is an understanding of how to implement CSR.

Achieving this requires a change in business climate, where companies place their social and environmental responsibilities at the core of their business decision-making. Likewise governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) need to play their role in shaping the business climate, with governments setting the right ‘rules of the game’ and NGOs engaging with businesses in a responsible and accountable manner. The key to this is partnership and cooperation, rather than antagonism, and all three actors have a role to play in successfully implementing CSR.

Much has been written telling companies to ‘do’ CSR, but a common complaint from my consultancy clients is that there is no book on how to go about CSR — especially for the more difficult industries where cheap and immediate fixes are not always available. Business leaders now accept that social goals are complementary to long-term business goals and that a responsibility for action lies with business. This is especially the case for companies working in ‘dirty’ industries and in the developing world — which calls for ‘hard’ CSR.

This book is an implementation guide on CSR for companies, big and small, working in the ‘hard’ industries and the developing world. The case studies help companies to understand what CSR is and how to put it at the core of their business decision-making.

Implementing corporate social responsibility

This book is based on case studies from a variety of companies across the business spectrum, demonstrating how CSR can be made to work in different circumstances. These cases are based on my visits to the site of operations and interviews with stakeholders, to document the benefits the company is bringing to local communities — but they are not my clients. These cases come from different industries; they include the very big and the very small but they all make CSR work in poverty-stricken areas of the world. What distinguishes these cases is that the companies were working in ‘hard’ industries — where CSR solutions were not immediately available — and that the companies concerned took a proactive approach to implementing CSR.

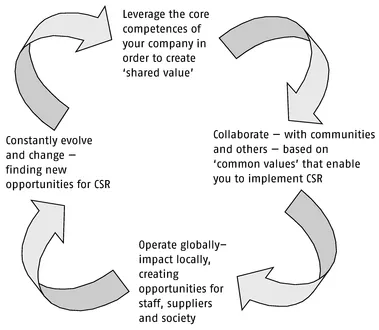

These companies are not perfect; some of them have arrived at their current policies by making mistakes in the past. But they have all made a commitment to CSR, which is now beginning to improve their business. They have had to make difficult decisions, balanced between competing priorities and these companies have had to engage their shareholders (and other stakeholders) in the debate. This has led to some very different approaches across the range of industries. Despite the differences between these companies we can distil six lessons from their operations on the key steps towards CSR in difficult industries:

- Leverage your core competences

- Collaborate based on common values

- Operate globally–impact locally: creating opportunities for staff, suppliers and society

- Use evolution and revolution: to change at every step along the value chain

- Work with, rather than against, good governments

- Cooperate with NGOs in a constructive way

This ongoing process can be visualised as a continuous cycle, as shown in Figure 1, all of which take place within a ‘business climate’ of constructive NGO and government collaboration.

Figure 1 Implementing CSR

In this book I explain each of these concepts with a detailed case study to illustrate how a company has applied this in real life. The cases used include:

- Leverage your core competences. Anglo American’s Zimele business development programme in South Africa

- Collaborate based on common values. Montana Exploradora and AMAC for community-based environmental management

- Operate globally–impact locally. Gildan, a major textile firm, conducting socially and environmentally responsible manufacturing in Honduras and Central America

- Engage in constant evolution. Scandic Hotels, implementing sustainability in an otherwise very polluting and unsustainable industry

- Work with good governments. Norway’s waste in electrical and electronic items is managed using a pro-market, pragmatic solution, creating opportunities for profit and environmental protection

- Cooperate with NGOs in a constructive way. Turner Broadcasting Europe finding ways to use its core competences in partnership with NGOs

It is important to recognise that implementing CSR is a process. Good companies will continuously seek to find ways to improve on their performance and to use CSR to gain strategic advantage over the competition. In so doing they should also seek to find new ways to create value for staff and society and to protect the environment. Using core competences and collaboration with communities in this way is not a new idea: organisations such as the World Business Council for Sustainable Development have been instrumental in leading the ‘core competence’ movement in CSR (advocating a mix of Core Competences, Partnerships and Localisation in their field guide to 'Doing Business with the Poor' in 2004). What is new is the idea that these all work together in the context of government and NGO collaboration — a 'business climate change' — for companies working in difficult industries in different parts of the world. It is the combination of skills, competences, collaborations and constant changes — set out in practice in these case studies — that delivers local development and private profit. This is an approach I refer to as ‘creating shared value’.

Shared value and common values

Underlying this approach is a view — an opinion based on experience — that companies perform best when they create ‘shared value’. Shared value is about increasing long-term returns to shareholders (shareholder value) through investing in value creation for staff, stakeholders, society and the environment. So implementing CSR is not about companies engaging in charity; on the contrary, it is about companies actively pursuing their self-interests but in the process creating value for society.

This approach has been labelled ‘proper selfishness’ by Charles Handy (1997). It means moving beyond CSR as charity, towards seeing CSR as an investment. This can be termed a win–win situation. I call it creating ‘shared value’; in many ways it is just good management. But, while the language of CSR may be new, the concept is not. Adam Smith discussed the concept in 1776:

Every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it... he in tends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages (Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776).

The challenge for the responsible company is to find ways in which the pursuit of shareholder interest also meets social interests. Companies that leverage their core competences, and put CSR at the core of their business model, do so in their own self-interest, but in doing so also benefit society. Reconciling the necessity of environmental protection — while distributing the advantages of economic growth — is key to understanding the opportunities for business in embracing CSR.

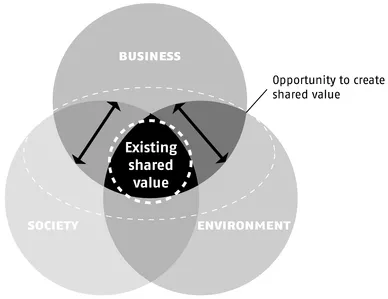

This concept is explained in Figure 2, which illustrates the ways in which businesses, society and the environment already create shared value. The challenge, and the opportunity, is to move businesses, society and the environment more closely together — building on common interests and common values — to create greater shared value.

However, there will always be cases where the pursuit of private profit leads to public ill. Actions that pollute the environment, destroy natural capital or harm individuals’ rights may well be profitable — but they are certainly not in the public good. This is where governments, in concert with businesses and NGOs, play a role in setting the ‘rules of the game’ within which companies need to operate. If activities that reduce the public good are made unprofitable — through taxation, legislation and popular pressure — then companies will cease to engage in them. The current situation, of publicly expecting companies to act responsibly but not punishing irresponsible companies, or punishing them insufficiently encourages a ‘moral hazard’. This is where regulations need to follow the ‘polluter pays principle’ to ensure that there is a financial incentive for responsible corporate behaviour.

Figure 2 Opportunities to create shared value

The point here is in making sure that irresponsible corporations do not gain a competitive advantage over responsible corporations (free-riding) and this can be achieved by changing the business environment in which companies operate. NGOs, governments and the public all have a role to play in this. However, companies should not wait for a change in the law in order for them to become responsible, as there are considerable opportunities in adopting CSR as a form of forward thinking management.

In addition, we also see that behind these successes are good government policies that encourage companies and NGOs to act in a responsible manner. These partnerships and collaborations need to be founded on common values: that is, shared definitions of the problems at hand and common understandings of how to address these issues. Having common values, shared goals and understandings is crucial to working in partnership with NGOs, governments and society.

The following chapters deal with how shared value can be created by implementing CSR. But first it is important to give some background on CSR, the social and environmental problems that face us today and the opportunities for action.

A brief history of corporate social responsibility

The idea that companies and businesses contribute to society is not new. Indeed, in many cultures the concept of business is inseparable from the society in which it works.1 In Western democracies there has always been a ‘privileged place of business’: an acceptance that economic growth and development are driven by companies and business people. This importance of business has led to certain privileges being enjoyed by business leaders: access to politicians, honours, awards and status. With these privileges have come responsibilities or noblesse oblige.2

This is not to contradict the ‘business of business is business’ approach, as outlined by Milton Friedman (1962), who stated that:

There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.

Rather, it emphasises that companies need to use their resources (here we call them core competences) and engage in activities to increase profits — but that this needs to be done within the ‘rules of the game’. The reality is that the ‘rules of the game’ are changing.

As large corporations have grown in power and influence, so too has the social and political consensus that companies need to accept responsibility for social and environmental problems, especially those that can be directly tied to the operations of the company. This responsibility goes beyond following the law (although this is essential) and it is distinct from charity or philanthropic activities; instead, it is about how companies conduct their business, taking responsibility for the impacts on society and the environment. In different markets this has taken different forms. Consumer goods retailing has tended to focus on specific issues along the supply chain: child labour, food miles and ethical sourcing. In other industries with less consumer appeal, such as the construction industry, CSR has yet to take hold. Meanwhile, some ‘dirty’ industries — especially the extractives — have faced considerable pressure to change their practices and considerable scepticism about the impact of the changes they have put in place.

Since the 1960s and 1970s, it has been recognised that the activities of businesses have negative as well as positive impacts on society and the environment. In the United States, in particular, corporate reports began to include comments on the environmental impact that companies were making. In these early years, much of this was little more than a public relations exercise, with the companies making non-binding commitments to environmental protection, with no clear link to business practice. These ‘greenwash’ reports were seldom informative and often backfired (Tepper Marlin and Tepper Marlin 2003), especially in the face of the growing strength and public profile of NGOs such as Greenpeace. Public pressure began to mount on companies to be held accountable for their actions and these pressures grew during the 1970s with a loss of faith by the public in their political and economic leaders. The ‘greenwash’ reports were no longer sufficient. The public demanded action and governments moved towards a general (and sometimes seemingly indiscriminate) toughening of the regulatory environment, forcing firms to be proactive in their reporting. Faced with government regulation, some businesses chose to be proactive. These new challenges presaged the ‘stakeholder’ approach to corporate reporting.

Corporate reporting

In 1989 Ben & Jerry’s, a North American ice cream manufacturer, began a new phase of corporate reporting. It provided not only financial reports aimed at shareholders, but also a ‘Stakeholders Report’ that detailed the firm’s relationships with its stakeholders: communities, employees, customers, suppliers and investors (Tepper Marlin and Tepper Marlin 2003). This approach to reporting on a firm’s social and environmental impact was new, ushering in a decade of initiatives aimed at the accurate reporting of company responsibilities. The 1990s saw a number of companies take the lead in voluntary reporting of how they were meeting their corporate social responsibilities. Because of the wide variety of different social...