![]()

![]()

Section 1

The Mediterranean Region:

A Unique But Neglected

Heritage

The Mediterranean area, because of its geography and its history, is an exceptional region. Its features, uniqueness and permanencies (the sea, the climate, the relief, biodiversity, its populations and its landscapes), which have been described so many times in literature, together encapsulate the ‘Mediterranean world’. They are briefly reviewed here.

Following on from this, the most evident signs of unsustainable development in the Mediterranean will be dealt with, by identifying the major geo political, socioeconomic, spatial and environmental trends in the last 20 to 30 years.

A unique heritage

Definitions of the Mediterranean area

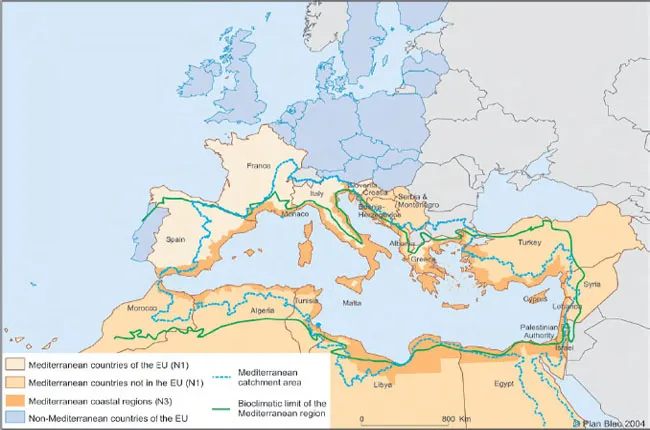

The Mediterranean area can be defined taking into account several dimensions (climate, vegetation, biodiversity, culture, etc.). According to the dimensions dealt with in this report, it will be described at the various levels shown in Figure 1.

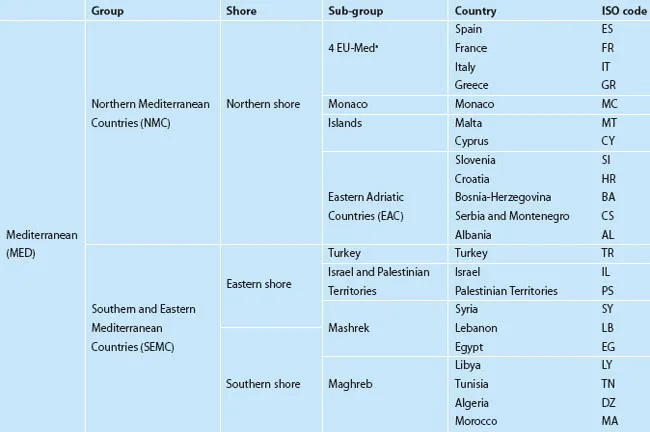

The first level (given the code N1 in the illustrations) comprises the 22 countries and territories bordering the Mediterranean (Table 1). Although, strictly speaking, this is a wider area than the Mediterranean bio-geographical region (defined on the basis of climate and vegetation), it is at this level that the institutional framework, the sectoral and economic policies and the directions of regional cooperation are defined, with all the many consequences for the region. Information about current trends is more easily accessible (long term series of statistics). At this first level (N1), the Mediterranean countries and territories occupy 8.8 million km2, or 5.7 per cent of the land area of the globe, and have 427 million inhabitants, 7 per cent of the world's population in 2000 (see Statistical Annex). Four demographic ‘heavyweight’ countries contain 58 per cent of the total: Turkey and Egypt (66 million inhabitants each), France (59 million) and Italy (57 million). For the purposes of analysis, the countries will occasionally be brought together in continents: the north Mediterranean countries (NMC) in Europe, and the southern and eastern Mediterranean countries (SEMC) of Africa and Asia, respectively, with regional subsets if necessary (Table 1). These groupings are by nature arguable. On the economic level, for example, Israel would be part of the northern Mediterranean countries and Albania of the ‘southern’ countries. Other groupings will be used if necessary. Turkey, for example, will sometimes be attached to the countries of the northern shore.

But whenever possible, the Mediterranean specificities are better illustrated at a second level (given the N3 code), closer to the Mediterranean eco-region and defined by the 234 coastal regions of the Mediterranean (administrative units of the NUTS1 3 level or equivalent of ‘départements’, ‘willayas’ or provinces, see Statistical Annex). The coastal region level (N3) thus defined represents 12 per cent of the total surface area of the countries and contains 33 per cent of their total population, 143 million permanent inhabitants in 2000. Some countries, such as Libya, Israel, Lebanon, Greece, Monaco, Cyprus and Malta, are very ‘Mediterranean’ from this point of view because their populations and their activities are concentrated in the Mediterranean coastal regions. This is less the case for Italy where the economic heart, the valley of the Po, is turned more towards Europe than the Mediterranean, and for Morocco, Spain and Turkey, which are continental countries and Mediterranean mainly because of their climate and vegetation, but open to other seas (the Atlantic, the Marmara Sea, the Black Sea). It is also less true of Egypt and Syria, with huge arid areas where human settlements are mainly organized around fertile valleys, oases and continental routes. It is even less true of France and Croatia (despite the importance of their Mediterranean coasts) and Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia-Montenegro, which to a large extent belong to non-Mediterranean temperate Europe.

Figure 1 A multi-dimensional Mediterranean region

Source: Plan Bleu

For the issues dealt with in Part 2 of the report, other geographic levels will be used:

Chapter 5 on Rural areas deals with an area close to the bio-climatic region (extended to arid regions);

Chapter 1 on Water refers to catchment areas formed by rivers watersheds (level NV) in the region;

a more accurate approach is needed for a better understanding of the changes on the terrestrial and maritime Mediterranean coast, focused on a narrow coastal strip.

Box 1 Share of the ‘Mediterranean coastal regions’ population in the countries, 2000 (N3,N1)

The proportion of inhabitants in the coastal regions (N3/N1) varies from country to country:

some countries have more than 80 per cent of their total population in the coastal regions: Greece, Israel, Libya, Malta, Cyprus, Lebanon and Monaco;

others have between 60 and 70 per cent: Tunisia and Italy (which alone has a quarter of the total Mediterranean coastal population);

around 40 per cent: Spain, Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, Albania and Palestinian Territories;

less than 20 per cent: Turkey, Morocco, Syria, Slovenia, Serbia-Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and France.

The report will also take into account the interactions of the Mediterranean with other areas such as the European Union (EU), with which interactions are extensive and the destiny closely linked. Figure 1 shows the superposition of these multiple areas (N1, N3, NV and bio-climatic region), which together make up, or interact with the Mediterranean area.

Table 1 List of Mediterranean countries and their abbreviations, N1

Note: The four riparian countries of the European Union before the integration in 2004 of Cyprus, Malta and Slovenia.

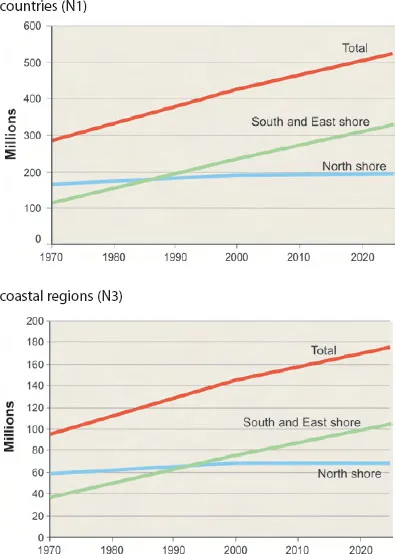

Population growth in the south and east

At the N1 country level (all countries together), the area has seen spectacular growth in population, from 285 million in 1970 to 428 million in 2000. The average growth rate was 1.36 per cent per year, equivalent to adding a country the current size of Bosnia-Herzegovina each year (Figure 2 and Statistical Annex). This is slightly less than the average world annual growth rate in the same period (1.7 per cent), so the share of the Mediterranean in the world population remains quite stable (7 per cent in 2000). Population growth is essentially in the SEMC (all the riparian countries from Morocco to Turkey) where, with 3.9 million more inhabitants per year, there was a record growth rate of 2.35 per cent per year between 1970 and 2000. This was five times higher than in NMC (0.45 per cent per year on average) during the same period. Thus, since 1990, the population in the SEMC has overtaken that in the NMC. Growth in the south was overestimated by Plan Bleu 89 (especially in Lebanon and Syria) since there has been a faster than predicted fall in fertility rate. The population growth forecasts, updated by Plan Bleu2 in 2001 show that the total population in the Mediterranean countries could reach 523 million by 2025, an average increase of 1.32 per cent per year, or 96 million more in 25 years (of which 92 million would be in the SEMC).

At the N3 coastal region level, the population increased from 95 million in 1970 to 143 million in 2000. The increase (48 million in 30 years) was mostly (80 per cent) in the SEMC. The changes were underestimated by Plan Bleu 89. The population growth rates in the Mediterranean coastal regions between 1985 and 2000 were, in most countries, higher than the maximum of the ranges in the 1989 scenarios. The forecasts for the coastal regions, updated in 2001, show that the population of these regions could reach 174 million by 2025, an average increase of 0.8 per cent per year (31 million in 25 years), mainly in the SEMC.

Figure 2 Population of countries and coastal regions, 1970–2025

Source: Plan Bleu, Attané and Courbage, 2001

The sea and trade

The sea is at the heart of the Mediterranean eco-region. It belongs to all the Mediterranean people; it has fashioned their history and is a natural link between them.

Partly enclosed by the straits of Gibraltar and the Dardanelles, which make possible water renewal because of heavy evaporation, the Mediterranean sea covers only 26 million km2, 0.8 per cent of the total surface area of the oceans. With small tides, the sea is as deep as an ocean (3700m in the Tyrrhenian sea and 4900m in the Ionian sea). It is fragmented into a ‘complexity of seas’ each possessing different biocenose and histories. The Sicily shelf that links Sicily to Tunisia at less than 400m in depth divides it into two and separates the western from the eastern basin. From the Gibraltar strait, the main natural entrance for water in the Mediterranean, the marine circulation makes a large cyclonic movement to the east that is divided into autonomous circuits and returns in deep currents to the west at the end of a 100-year water renewal cycle. These straits are the third busiest in the world (with 240 ships a day), and are therefore particularly at risk of pollution.

The sea shelters a very varied living world. The marine fauna, including 600 species of fish, benefits from the diversity of the nature at the bottom of the sea. However, it is not very abundant because of poor water productivity (narrowness of the continental shelves, low input of organic matter). The coastal zone, which is the main area of primary production for the food chain, concentrates fauna and flora in a limited and particularly vulnerable area. Human pressures on the coasts threaten many species (turtles, monk seals, gruper) and very valuable habitats. The Mediterranean, and especially the narrow areas between the northern and southern shores (Gibraltar, Sardinia, the strait of Sicily, Crete, Cyprus, the Dardanelles), is on one of the main migration routes for terrestrial avifauna between Europe and Africa.

The sea has not always been the natural link between land and people, although it has often been described as such. The Mediterranean region, despite the building of great empires, was for many centuries divided into autonomous areas and it took a long time for navigation to become safe. However, maritime links have made the Mediterranean Basin become an historical area that has been essential for human trade to such an extent that Fernand Braudel described it as the prototype of a ‘world economy’, with its simultaneously diverse and unified nature and its heritage of civilization. This ‘world economy’ culminated in the 16th century by associating, in a relationship of conflictual complementarity, the great empires and powers of the time as well as their populations. Since that time, the emergence of the pole posi...