- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An interdisciplinary text on the world's savannas, covering the geography, ecology, economics and politics of savanna regions. Savannas are a distinct vegetation type, covering a third of the world's land surface area and supporting a fifth of the world's population. There has been a wide range of literature on the subject, but the majority of work has focused on the ecology or development of savanna areas, ignoring the wider interdisciplinary issues affecting contemporary savannas. World Savannas aims to buck this trend, providing students with an up-to-date and comprehensive introduction to the global importance of savannas.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Savannas by Jayalaxshm Mistry,Andrea Beradi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The savanna ecosystem

1.1 Introduction

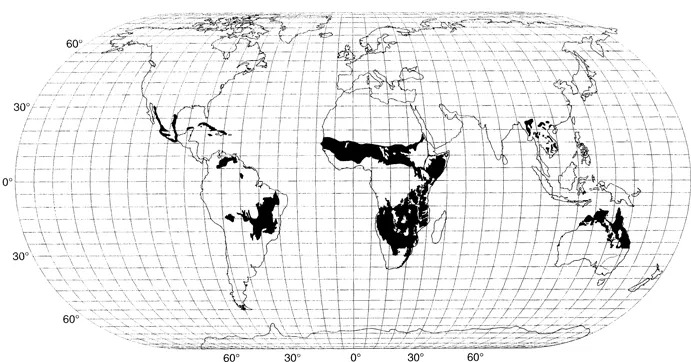

Savannas are the most common vegetation type in the tropics and subtropics (Solbrig, 1991) (Figure 1.1). They can be loosely defined as ecosystems with a continuous and important grass/herbaceous stratum, a discontinuous layer of trees and shrubs of variable height and density, and where growth patterns are closely associated with alternating wet and dry seasons (Bourlière and Hadley, 1983). Rainfall in savannas is highly seasonal, and the dry season can last from 2 to 9 months. Not only does this affect plants and animals, but it is also a major limitation to over one-fifth of the world’s population, who live in or around savanna areas (Frost et al., 1986). Many of these communities rely on subsistence agriculture or pastoralism. Productivity of crops and pastures is therefore governed by the uneven and often unpredictable nature of rainfall distribution. This is exacerbated by the generally nutrient-poor status of many savanna soils. Nevertheless, over time, plants, animals and humans have adapted to the savanna environment, and today savannas support a rich diversity of species and human cultures.

1.2 The key ecological determinants

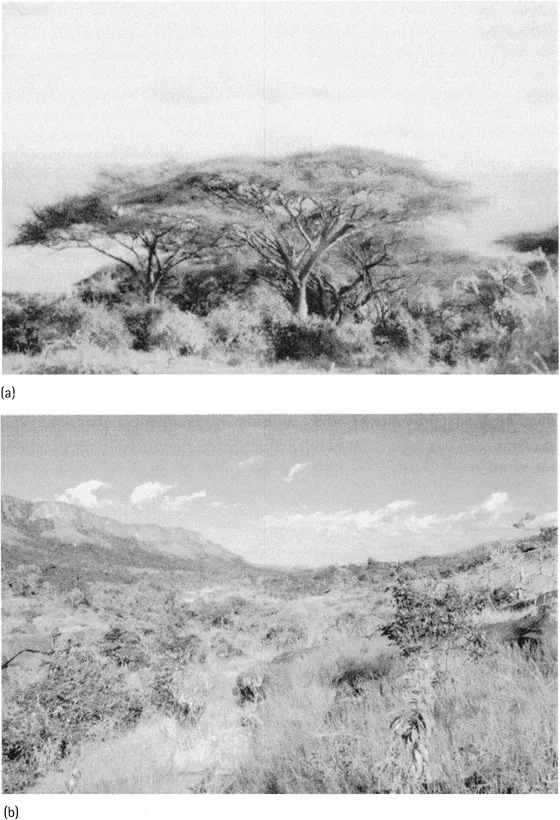

Savannas are extremely heterogeneous ecosystems at different spatial and temporal scales (Figure 1.2). Over a landscape or at the patch scale, from a week to a century, savanna boundaries fluctuate through a variety of causal factors including the physical environment and human land use. They are also found intermingled with other vegetation forms, such as gallery forest and grassland. This heterogeneity has led to much confusion over the definition of savannas. In addition, there was a common misconception that all savannas were derived, i.e. they were previously forest, but through disturbance such as human activity, they became savannas. This may be the case for some areas (see Section 1.6.5), but palaeoevidence indicates that the majority of savannas are natural and ancient.

The actual word ‘savanna’ is thought to originate from an Amerindian word which, in a work on the Indies published in 1535, was used by Oviedo y Valdes to describe ‘land which is without trees but with much grass either tall or short’ (Bourlière and Hadley, 1983). Subsequently, its use was extended to include trees, as by Schimper in 1903. The term, however, has undergone constant metamorphoses, and has been used as either a climatic or a vegetation concept (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Distribution of the world’s savannas.

(Reproduced by kind permission of Justin Jacyno)

Figure 1.2 The large range of savanna types has led to confusion over its definition, (a) An East African savanna; (b) a Brazilian savanna.

(Photographs by the author)

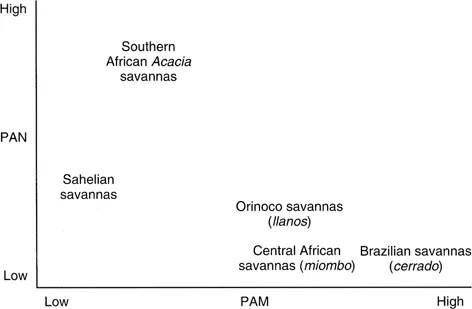

The huge range of definitions has been a major obstacle in attempts to relate research results and observed responses to disturbance and management in one savanna to those in another. These disparities brought together a group of savanna ecologists from around the world, in an attempt to identify a classifica-tory framework from which global as well as local comparisons could be made between savanna types, and between different components of savannas, e.g. tree or grasses. The group of savanna ecologists discussed the problem at a Responses of Savannas to Stress and Disturbance (RSSD) workshop sponsored by the International Union of Biological Sciences, in Harvard Forest, Massachusetts, USA. A conceptual model was developed, based on four key ecological determinants recognised as controlling the structure and function of savannas (Frost et al., 1986; Goldstein et al., 1988; Medina, 1993). These determinants are water availability, nutrient availability, fire and herbivory (Stott, 1991a). The model, however, evolves around the two factors considered to have primary control: plant-available moisture (PAM) and plant-available nutrients (PAN). Termed the PAM/PAN pi ane (Figure 1.3), this model allows the substitution of biological meaningful measures, i.e. PAM and PAN, for purely physical variables, thus enabling ready comparisons at various levels of savanna sites and plants. For example, PAM could be measured using factors such as the number of ecologically humid days (i.e. the period when growth is not limited by water availability) and/or the number of days in which rainfall exceeds evapotranspiration, and PAN could be based on the sum of exchangeable bases (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Na+).

| Definitions of savanna | Authors |

| Climatic | |

Ecosystems which lie in the tropical savanna (Aw) and monsoon (Am) climatic zones, largely between the latitudes of Cancer and Capricorn, where annual precipitation is between 250 and 2000 mm, most of which falls in the wet season | Köppen (1884, 1900) |

Any formation or landscape within the region experiencing a winter dry season and summer rains is a savanna. | Jaeger (1945), Troll (1950) and Lauer (1952) |

Ecosystems bound by dry forests at higher rainfall (> 1000 mm), by thorn forests at lower rainfall (< 500 mm), and by thorn steppe and temperate savannas at lower temperatures (< 18 °C) | Holdridge (1947) |

Ecosystems with low’ to moderate rainfall (500–1300 mm) and high mean annual temperatures (18–30 °C) | Whittaker (1975) |

| Vegetation | |

A mixed physiognomy of grasses and woody plants in any geographical area | Dansereau (1957) |

A mixed tropical formation of grasses and woody plants, excluding pure grasslands | Walter (1973) |

Open formations dominated by grasses, in the lowland tropics, where trees and shrubs, if present, are of little physiognomic significance | Beard (1953) and Whittaker (1975) |

Figure 1.3 The PAM/PAN plane, and hypothetical distribution of some savanna formations (after Frost et al., 1986).

Scale is fundamental to the model as both PAM and PAN will function differently over discrete levels of space and time. The four geographical scale divisions considered in the model are patch, a small area that is homogeneous in relation to some characteristic such as vegetation or topography; catena, a topographically determined unit in which a series of patches may be linked through a continuum of processes; landscape, a contiguous set of catenas; and region., a set of landscapes (Solbrig, 1991).

1.2.1 Plant-available moisture (PAM)

Precipitation in savannas varies from about 300 mm year−1 to over 1600 mm year−1, and there is a dry season of between 2 and 10 months (Frost et al., 1986) (Table 1.2). Savannas are characterised by a positive water regime (precipitation greater than evapotranspiration) during the rainy season, and a negative one during the dry season. The spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall is often highly variable, within a wet season, during a year, and between years.

Temperatures depend on the altitude and the latitudinal position of the savanna. Savannas located at higher elevations, such as some Brazilian savanna (cerrado) localities, and at the margins of the tropical zone, such as those in southern Africa and southern South America, can experience extremely low temperatures, and differences between mean January and mean July temperatures can be more than 10 °C (Nix, 1983). The latitudinal position also determines the length of the day and distribution of solar radiation.

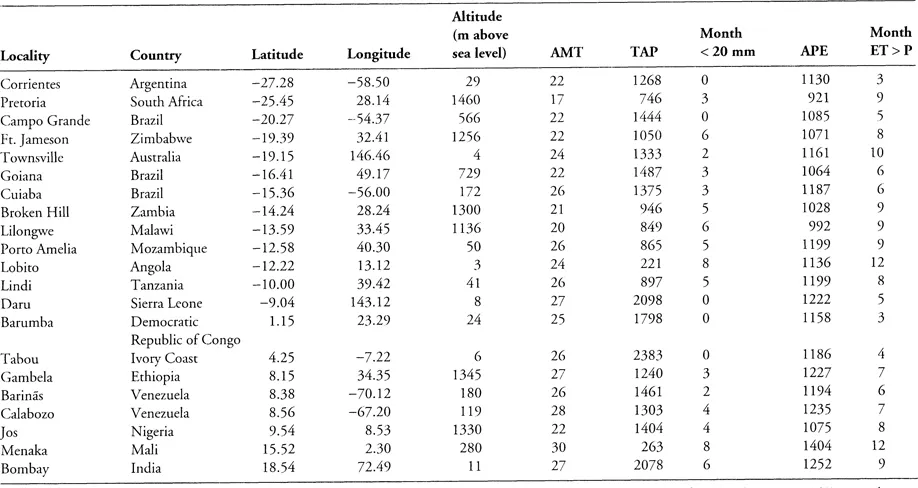

Table 1.2 Climatic variables of some savanna locations (after Solbrig, 1996)

AMT = annual mean temperature (°C); TAP = total annual precipitation (mm); Month < 20 mm = number of months in which rainfall is less than 20 mm; APE = annual potential évapotranspiration (mm); Month ET > P = number of months in which evapotranspiration is greater than precipitation.

1.2.2 Plant-available nutrients (PAN)

Savanna soils vary widely, depending on a variety of soil-forming factors including climate, geology, geomorphology, topography, the vegetation cover and animal activity (Montgomery and Askew, 1983). However, most tropical savannas occur on old and weathered surfaces, the result of geomorphological processes over millions of years (Cole, 1986). As a result, many savanna soils have low levels of nutrients (soil types: oxisols and ultisols) since they have been subject to soil-forming processes for prolonged periods of time. Generally, the higher moisture regimes of American, Australian and West African savannas make them extremely nutrient-poor compared to drier savannas, where nutrient levels are higher. This is, of course, subject to smaller-scale variations in soil-forming factors outlined above. Overall, savannas have small amounts of exchangeable calcium, magnesium and phosphorus, and a low cation exchange capacity; highly weathered soils also have high levels of exchangeable aluminium, which can reach toxic levels (Frost et al., 1986).

1.2.3 Measuring the PAM/PAN plane

The PAM/PAN plane is a useful concept, in that if a savanna site can be positioned on the plane within an acceptable level of precision, it can be used to make predictions about the site’s inherent structure and about various functional attributes that are difficult to measure, such as primary productivity, the seasonal course of evapotranspiration, nitrogen dynamics, and responses to fire and herbivory. It can also enable predictions to be made about possible changes in savannas in response to phenomena such as climate change. These inferences can then be extended to other sites with similar locations on the PAM/PAN plane.

However, Belsky (1991) notes that until the axes of the PAM/PAN plane are associated with quantifiable variables, the model provides little improvement over the earlier models. Few studies have as yet attempted to characterise PAM and PAN. One such work was by Walker and Langridge (1997), in which their objective was to find the optimal values (a trade-off between increasing complexity and the likelihood of obtaining the necessary data) for PAM and PAN, so as to be able to develop indices for comparing the savanna structure of 20 different sites in Australia. Their findings showed that general predictions of woody leaf, grass and total biomass did not need a detailed water budget analysis, but could be estimated from simple values of total rainfall, mean number of rainy days, potential evapotranspiration and soil texture. The best overall predictor of PAM was mean annual rainfall divided by potential evap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 The savanna ecosystem

- Chapter 2 The cerrado of Brazil

- Chapter 3 The Ilanos

- Chapter 4 The miombo of central Africa

- Chapter 5 The savannas of West Africa

- Chapter 6 The savannas of East Africa

- Chapter 7 The savannas of southern Africa

- Chapter 8 The dry dipterocarp savannas of mainland Southeast Asia

- Chapter 9 The savannas of Australia

- Chapter 10 Savannas in the twenty-first century

- Appendix: Savanna and related Internet sites of interest

- Glossary of terms

- Bibliography

- Index