eBook - ePub

Architectures for Intelligence

The 22nd Carnegie Mellon Symposium on Cognition

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architectures for Intelligence

The 22nd Carnegie Mellon Symposium on Cognition

About this book

This unique volume focuses on computing systems that exhibit intelligent behavior. As such, it discusses research aimed at building a computer that has the same cognitive architecture as the mind -- permitting evaluations of it as a model of the mind -- and allowing for comparisons between computer performance and experimental data on human performance. It also examines architectures that permit large, complex computations to be performed -- and questions whether the computer so structured can handle these difficult tasks intelligently.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Architectures for Intelligence by Kurt Van Lehn, Kurt Van Lehn, Kurt Van Lehn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | The Place of Cognitive Architectures in a Rational Analysis |

Department of Computer Science and Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University

The basic goal of a theorist in specifying a cognitive architecture is to specify the mind’s principles of operation and organization much like you would specify those of a computer. Any cognitive phenomena should be derivative from these principles. As this conference gives witness, there are many cognitive architectures. This chapter will try to make some claims about the role of architectures generally in psychological theory, but it will do this by taking as examples three of the architectures which figure prominently at Carnegie Mellon University. There is the Soar architecture of Laird, Newell, and Rosenbloom (1987) my own ACT* architecture (Anderson, 1983), and the PDP architecture of McClelland and Rumelhart (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1986, Rumelhart & McClelland, 1986).

Now that there are numerous candidates for cognitive architectures, one is naturally led to ask which might be the correct one or the most correct one. This is a particularly difficult question to answer because these architectures are often quite removed from the empirical phenomena that they are supposed to account for. In actual practice one sees proponents of a particular architecture arguing for that architecture by reference to what I call signature phenomena. These are empirical phenomena that are particularly clear manifestations of the purported underlying mechanisms. The claim is made that the architecture provides particularly natural accounts for these phenomena and that these phenomena are hard to account for in other architectures.

In this chapter I will argue that the purported signature phenomena tell us very little about what is inside the human head. Rather they tell us a lot about the world in which the human lives. The majority of this chapter will be devoted to making this point with respect to examples from the SOAR, ACT*, and PDP architectures. At the end of the chapter, I will turn to the issue of the consequences of this point for the role of cognitive architectures.

As a theorist who has been associated with the development of cognitive architectures for 15 years, I should say a little about how I came to be advocating this position. I have been strongly influenced by David Marr’s (1982) meta-theoretical arguments in his book on vision which are nicely summarized in the following quote:

An algorithm is likely to be understood more readily by understanding the nature of the problem being solved than by examining the mechanism (and the hardware) in which it is solved. (p. 27)

Marr made this point with respect to phenomena such as stereopsis where he argued that one will come to an understanding of the phenomena by focusing on the problem of how two two-dimensional views of the world contained enough information to enable one to extract a three-dimensional interpretation of the world and not by focusing on the mechanisms of stereopsis. He thought his viewpoint was appropriate to higher-level cognition although he did not develop it for that application. As recently as a few years ago I could not see how his viewpoint applied to higher-level cognition (Anderson, 1987). However, in the last couple of years I have come to see how it would apply and have realized its advantages. Before specifying its application let us briefly note three advantages of focusing on the information-processing problem and not the information-processing mechanisms:

1. As Marr emphasized, the understanding the nature of the problem offers strong guidance in the proposal of possible mechanisms. If anything this is more important in the case of higher-level cognition where we face a bewildering array of potential mechanisms and an astronomical space of their possible combinations which we must search in trying to identify the correct architecture.

2. Again as Marr emphasized, this allows us a deeper level of understanding of these mechanisms. We can understand why they compute in the way they do rather than regarding them as random configurations of computational pieces.

3. Cognitive psychology faces fundamental indeterminacies such as that between parallel and serial processing, the status of a separate short-term memory, or the format of internal representation. Focusing on the information-processing problem allows us a level of abstraction that is above the level where we need to resolve these indeterminacies.

A RATIONAL ANALYSIS

The basic point of Marr’s was that if there is an optimal way to use the information at hand the system will use it. I have stated this as the following principle:

Principle of Rationality. The cognitive system optimizes the adaptation of the behavior of the organism.

One can regard this principle as being handed to us from outside of psychology—as a consequence of basic evolutionary principles. However, I do not want to endorse the principle on such an evolutionary basis because there are many cases where evolution does not optimize. Of course, there are many cases where it does (for a recent discussion see Dupre, 1987). On one hand there are the moths of Manchester and on the other hand, as Simon notes in his companion article, there are the fauna of Australia. It is an interesting question just where and how we would expect evolution to produce optimization, but this is an issue that I neither have space nor competence to get into. Rather, I view the aforementioned principle as an empirical hypothesis to be judged by how well theories that embody the principle of rationality do in predicting cognitive phenomena.

On the empirical front it might seem that the principle of rationality is headed for sure disaster in accounting for human cognition. It is the current wisdom in psychology that man is anything but rational. However, I think many of the purported irrationalities of man disappear when we take a broader view of the human situation. Among the relevant considerations are the following three:

1. We have to bear in mind the cost of computing the behavior. Many think that the problem with the traditional rational man model of economics is that it ignores the cost of computation. Thus we need something like Simon’s (1972) bounded rationality where one includes computation cost in the function to be optimized. For instance, in principle a rational person should be able to play a perfect game of chess told the rules of chess but this ignores the prohibitive cost of a complete search of the game tree.

2. The adaptation of the behavior may be defined with respect to an environment different than the one we are functioning in. For instance, one might wonder why human learning mechanisms do so poorly at picking up knowledge in a school environment. I think the answer is that it is not a school environment that they are adapted to.

3. One must recognize that traditional tests of human rationality typically involve normative models that make no reference to the adaptiveness of the behavior. For instance, normative models typically advocating maximizing wealth while the evidence is that there is a negative correlation between wealth and number of surviving offspring (Vining, 1986). The implication is that one must look critically at the functions which we are trying to optimize in a rational analysis.

With these caveats it is my claim that one can use a rational approach as a framework for deriving behavioral predictions. Developing a theory in a rational framework involves the following six steps:

1. Precisely specify what the goals of the cognitive system are.

2. Develop a formal model of the environment that the system is adapted to (almost certainly less structured than the experimental situation).

3. Make the minimal assumptions about computational costs.

4. Derive the optimal behavioral function given (1)–(3).

5. Examine the empirical literatures to see if the predictions of the behavioral function are confirmed.

6. If predictions are off, iterate.

The theory in a rational approach resides in the assumptions in (1)–(3) from which the predictions flow. I refer to these assumptions as the framing of the information processing problem. Note this is a mechanism-free casting of a psychological theory. It can be largely cast in terms of what is outside of the human head rather than inside. As such it enjoys another advantage which is that its assumptions are potentially capable of independent verification.

What I would like to do in the majority of the chapter is to apply this rational analysis to one signature phenomenon for each of the three architectures mentioned in the introduction—SOAR, ACT*, and PDP.

SOAR—POWER LAW LEARNING

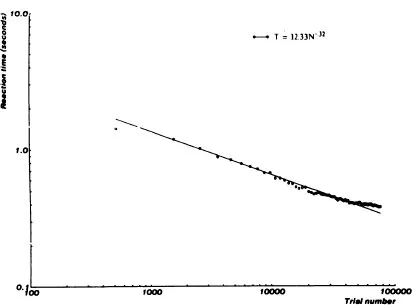

The signature phenomenon I would like to consider for the SOAR theory is power-law learning which is referenced in many of the SOAR publications. Figure 1.1 illustrates data from the Siebel (1963) task which Rosenbloom, Laird, and Newell (1987) have simulated within SOAR. In this task subjects were presented with a panel of ten lights, some of which were lit. They had to press the corresponding fingers on their hands. Subjects saw all configurations of lights except the one in which no lights were lit. Figure 1.1 plots their performance time against the amount of practice which they had. Both scales are logarithmic. As can be seen the relationship is linear implying that the performance measure is a power function of practice. As Newell and Rosenbloom (1981) discussed, such power functions are ubiquitous. The effects can be quite extensive. The data plotted by Seibel covers 40,000 trials.

FIG. 1.1. Data from Siebel (1963) plotting time to respond against amount of practice.

In the Soar model, the power law falls out of the chunking learning mechanism plus some critical auxiliary assumptions. Chunking refers to the collapsing of multiple production firings into a single production firing that does the work of the set. In the Seibel task, subjects might chunk productions that will press subsets of lights simultaneously rather than separately. It is assumed that each chunk produces a performance enhancement proportional to the number of productions eliminated. Chunks are formed at a constant rate—either on every opportunity or with equal probability on every opportunity. The final critical assumption is that as chunks span larger and larger units the number of potential chunks grows exponentially. This is fairly transparent in the Seibel task where there are 2n productions needed to encode all chunks of n lights. As a consequence of the last assumption, learning will progress ever more slowly because it takes more experience to encounter all of the larger chunks.

I have always had a number of haunting doubts about the SOAR explanation of the Seibel task. Some of these were expressed in Anderson (1982, 1983). One is that the exponential growth in chunks does not seem true of simple memory experiments (such as paired-associate learning) which produce beautiful power-law learning functions. The second is that the analysis has no place for forgetting effects which must be taking place. So we know by the time of the 40,000 trial of the Seibel task the benefit of the first trial should be fading. Third, the model has no provision for massing effects. We know that as many trials are massed together they loose their effectiveness. Note that the massing effect and forgetting effects are at odds with each other. One is optimized by massing the trials together and the other by spacing them apart.

I will offer a rational analysis of power-law learning which will also explain the forgetting and massing functions. This will be part of a larger rational analysis of human memory which is the topic of the next section.

A RATIONAL ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MEMORY

The claim that human memory is rationally designed might strike one at least as implausible as the general claim for the rationality of human cognition. Human memory is always disparaged in comparison to computer memory—it is thought of as slow both in storage and retrieval and terribly unreliable. However, such analyses of human memory fail both to understand the task faced by human memory and the goals of memory. I think human memory should be compared with information-retrieval systems such as the ones that exist in computer science. According to Salton and McGill (1983) a generic information-retrieval system consists of four things:

1. There is a data base of files such as book entries in a library system. In the human case these files are the various memories of things past.

2. The files are indexed by terms. In a library system the indexing terms might be keywords in the book’s abstract. In the human case the terms are presumably the concepts and elements united in the memory. Thus, if the memory is seeing Willie Stargell hit a home run the indexing terms might be Willie Stargell, home run, Three Rivers Stadium, etc.

3. An information-retrieval system is posed queries consisting of terms. In a library system these are suggested keywords by the user. In the case of the human situation, it is whatever cues are presented by the environment such as when someone says to me “Think of a home run at Three Rivers Stadium.”

4. Finally, there are a set of target files desired by which we can judge the success of the information retrieval.

One thing that is very clear in the literature on information-retrieval systems is that they cannot know the right files to retrieve given a query. This is because the information in a query does not completely determine what file is wanted. The best information-retrieval systems can do is assign probabilities to various files given the query. Let us denote the probability that a particular file is a target by P[A].

In deciding what to do informational-retrieval systems have to balance two costs. One is what Salton and McGill call the precision cost and which I will denote Cp. This is the cost associated with retrieving a file which is not a target. There must be a corresponding cost in the human system. This is the one place where we will see a computational cost appearing in our rational analysis of memory.

The other cost Salton and McGill call the recall cost and we will denote it CR. It is the cost associated with failing to retrieve a target. Presumably in most cases it is much larger than the precision cost for a single file or memory.

Given this framing of the information-processing problem we can now proceed to specify the optimal information-processing behavior. This is to consider memories (or files) in order of descending P[A] and stop when the expected cost associated with failing to consider the next item is greater than the cost associated with considering it or when

We now have a complete theory of human memory except for one major issue—how should the system go about estimating P[A]. I propose...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- PART I COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

- PART II ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

- Author Index

- Subject Index