![]()

1

BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

J. Bruce Tomblin

Systematic empirical research on individual differences in child language development and disorders emerged during the 1960s. Since that time, our understanding of the scope and nature of language across children and through development has expanded immensely. We now have rich theories and a wide range of methods for describing many features of individual differences of language in ways that are developmentally appropriate and theoretically well motivated. These theories and methods have yielded a much better understanding of the nature of language growth, the possible factors that contribute to individual differences and disorders in this growth, and the impact these differences have on the lives of children. The progress that has been made has largely come from the efforts of many individuals and small groups of academicians conducting research on relatively small samples of children sampled from clinical services units along with typically developing controls sampled as volunteers and thus often from advantaged homes. Furthermore, most of this research has employed cross-sectional designs with a focused set of research questions. Many of these characteristics arise naturally out of the limited resources available to most researchers in child language development and disorders.

In the pages that follow, we authors will describe a longitudinal project that spanned 10 years beginning in 1996 and terminating in 2006. This research project was concerned with advancing our understanding of individual differences in language development during the school years and represented a break from many of the earlier research practices described above. This research project represented a large-scale longitudinal collaborative study of children who were recruited using epidemiological sampling methods. Because of the size of the sample and the longitudinal design, the project could address questions that were often out of reach of the typical research study on language development and disorders. As such, this project may be viewed as an industrial-sized research effort, and in this regard, we acknowledge that size is not always a positive attribute. Because our research questions were wide ranging, we were not always able to examine all questions in depth or with the flexibility that one might have with a smaller, more focused project. Thus, we do not present this work with the claim that it is better than other research efforts, but rather that it provides complementary strengths to the existing literature.

In addition to this research project having an industrial-sized quality, it was admittedly opportunistic. As I will describe soon, this study arose from our having conducted a large-scale epidemiological study for the purposes of estimating the prevalence of specific language impairment (SLI). The availability of this sample presented a rare opportunity for large-scale research, and this required that a group of research collaborators be formed. Most research collaborations are formed around a common viewpoint and interests in a particular problem. Although we shared a common interest in language disorders, this collaboration was not formed around common perspectives or necessarily common theoretical viewpoints. We saw this diversity as an asset in that we would study a common cohort of children from a range of different perspectives. The pages that follow will provide the insights drawn from this common cohort of children, but will often be expressed with varied voices and perspectives.

A PERSPECTIVE ON THE IOWA LONGITUDINAL STUDY: DEFINING AND EXPLAINING LANGUAGE DISORDER

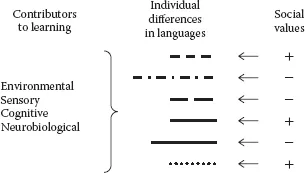

As I noted, the collaborators in this project were not required to “buy in” to a single common rationale for this research program. As the person who convened this collaboration, I had my own perspectives, which did shape the broad structure of the study. To some degree, the viewpoints that I held at the initiation of the project evolved further during the study, but the general thinking remained. In the late 1970s a major portion of my teaching was either in the clinic with students preparing to become clinicians or in the classroom with them. Much of my teaching had to do with the clinical management of developmental language disorders and yet I realized at that time that I did not explicitly address when or why we determine that a child presented with a language disorder. Furthermore, there was very little guidance in the literature on this topic. So I set about learning how other disciplines such as medicine or clinical psychology came to establish the basis for illnesses or disorders. My reading of this literature led me to develop a model for defining and explaining language disorders. A schematic of this model is shown in Figure 1.1. Over the years, I’ve presented various versions of this model (Tomblin, 1991, 2006; Tomblin & Christiansen, 2010), but the core ideas have remained. This core is that explaining and defining language disorder requires two types of explanation. One is concerned with how individual differences arise; the second is how and why individual differences are carved up into categories concerned with health and illness or normal and disordered conditions.

As shown in Figure 1.1, the central feature of this model concerns individual differences. It is an empirical fact that although language development is often described as a universal and uniform feature of humans, not all individuals within any language community are equally facile with language development or use. In some aspects of language, such as grammar, individual differences may be less apparent in adults, but even among adults, variability can be found in certain language usage tasks. Not only is it obvious that individual differences in language exist, it is also the case that without these differences it would not be possible to have a notion of disorder. If we perform a mind experiment in which all individuals are equal with respect to language performance, or any other trait for that matter, it would be impossible for us to consider the notion of a language disorder. Thus, the existence of individual differences is a necessary condition for any kind of construct of disorder.

Figure 1.1 A characterization of causal sources for language impairment arising from the convergence of social values and learning systems onto individual differences.

If individual differences provide the basis for disorder, we can then ask the question “how do these arise?” This is one of the two explanatory questions I posed earlier. In many people’s minds this question will also lead to answering it. If we ask the question about the cause of individual differences, it suggests that we believe that there are mechanisms or processes that give rise to these individual differences. However, many of those within important research disciplines concerned with language such as cognitive psychology and linguistics act as though these individual differences occur at random and thus represent noise in the causal mechanisms that give rise to language and cognitive development. This type of thinking is often found in cognitive psychology and linguistics and reflects a focus in these disciplines on universal (nomothetic) features of language and cognition. Thus, there are invariant mechanisms that operate in the same way and to the same degree in all individuals; however, noise enters into these operations, but it is unsystematic and uninteresting. In fact, it is much more likely that these individual differences across the range of development and function are principled and governed by systematic variations in the operations of natural biological and cognitive systems. These alternative views of individual differences are long-standing. Cronbach (1957) referred to them as representing two disciplines within psychology. The former view was common in experimental psychology and now in cognitive psychology. The alternative view, that individual differences are principled, is often found among those who work within the framework of differential psychology (psychology of individual differences). Cronbach noted that the differential psychologist “regards individual and group variations as important effects of biological and social causes” (Cronbach, 1957, p. 674). If we adopt the perspective of the differential psychologist, we could hypothesize that some forms of individual differences represent a “normal” state that arises from the proper operations of the mechanisms that contribute to language, and then there are other forms of individual differences that arise from defective mechanisms. That is, children with language disorder represent a subgroup of individual differences arising from a unique set of causes. Thus, if we study the causes of individual differences in language development using the appropriate scientific methods, we will be able to also discover and explain when and why some of these individual differences are disordered.

An alternative viewpoint, and one that I have preferred, acknowledges that there are principled causal mechanisms that give rise to individual differences; however, the variations in the operations of these mechanisms, as well as the functional variations in language that arise from them, are not inherently good or bad or represent states of health and illness. Instead, within this view, claims of health, illness, disorder, etc., are examples of cultural artifacts such as chairs, airplanes, or cooking pots. These are things invented by humans and reflect the social values of the inventor. In this regard, notions of illness and disorder are grounded in cultural values or norms that reflect what a society prizes or despises in its members. A very good example of this can be found in our field with regard to the health status of hearing loss. The Hearing culture views a hearing loss as a type of illness whereas the Deaf culture does not. Thus, within this perspective, forms of individual differences do not have an inherent quality of “normal” and “disordered” but rather these are culturally assigned. In some literature, this view is referred to as normativism, wherein the notion of norm refers to a social value. Figure 1.1 thus shows that these social values represent a separate causal path for explaining when and why some forms of individual differences come to be disordered. This path is distinct from the mechanisms that give rise to the individual differences.

In taking this view, my perspective in this research project was that we wanted to identify those situations in which children’s lives are negatively affected by their language status. In this regard, studying outcomes is not just looking at by-products of language disorder, but rather become the means by which we determine when individual differences represent language impairment. In order to do this, we need to have longitudinal data about domains in children’s lives that are culturally salient. I should also note that this viewpoint leads us to consider that the construct of language disorder as applied to any given child is at best probabilistic. Because I no longer view language disorder as a condition within the child, but rather a condition that exists between the child and the world the child will live in, we cannot say with certainty that the child will or will not face negative consequences during his/her life. Thus, our view of language disorder becomes a probabilistic statement rather than an absolute statement. In this regard, language disorder is not something children have in the same way that they have brown eyes or curly hair. These children may “have” certain language abilities and these may be enduring, but the particular ability the child possesses only confers some degree of risk for socially defined troubling outcomes. The risk and hence what we might consider disorder is probabilistic. In order for us to construct these probabilities, it is necessary to examine a large sample of children who span the range of language abilities and within these children we must measure both individual differences in language as well as individual differences in key outcomes. Then we need to examine the association between these. Indeed, this was one of the principal objectives of the longitudinal study.

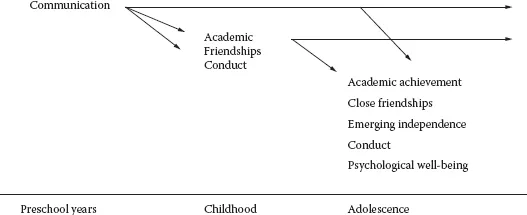

DEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOMES AS COMPETENCE

Within this framework, some outcomes are more important than others. We are particularly interested in outcomes that are socially and personally valued. This introduces a new challenge to our research. How do we determine what developmental outcomes are socially valued? To some extent we are aided in this by the fact that we are members of the society into which these children are entering and therefore our intuitions can provide a reasonable guide. Another helpful source for framing this comes from researchers who have been examining threats to child development in the form of risks and factors that moderate these risks and as such lead to resilience. At the core of this research on risk and resilience has been the concept of developmental competence. Masten defined competence as “adaptation success in the developmental tasks expected of individuals of a given age in a particular cultural and historical context” (Masten et al., 1999). Societal expectations of individuals change as they age. This variation in expectation is incorporated in Zigler and Glick’s notion of salient developmental tasks (Zigler & Glick, 1986). Roisman and colleagues have stated that “salient developmental tasks represent the benchmarks of adaptation that are specific to a developmental period and are contextualized by prevailing sociocultural and historically embedded expectation” (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004, p. 123). Because expectations vary with development, there are transitional points in life where old competences are diminishing in saliency and new ones are emerging to become salient (Roisman et al., 2004). As these new competences emerge, they build on the prior competences and also upon new cultural supports that motivate growth. For instance, within many cultures, it is likely that language development itself represents a salient developmental task of early childhood. Subsequently, during later childhood, academic and peer relations become salient tasks but these will be influenced in part by the earlier accomplishment of language development. Thus, as shown in Figure 1.2, competences can have a cascading relationship. Masten has proposed that failures in the development of competence at a later stage of development can often be traced to failures of development at earlier stages of development.

Figure 1.2 Developmentally salient competences across childhood demonstrating the cascade of communication competence over development.

Our current interest in this research program is the developmental period of childhood and adolescence. Therefore we can ask, within the culture of the United States, what are the developmentally salient tasks of childhood and adolescence around which we can define good or poor competence? During the elementary school years of childhood competence has been found to consist of three domains: “(a) getting along with peers (peer acceptance and having friends), (b) academic achievement, and (c) rule-abiding conduct (compliance with authority at home and school)” (Masten et al., 1995, p. 1335). These three domains of competence persist into adolescence but become refined. Academic competence in adolescence is reflected by level of education and school performance reflected in grades and teacher and parent report of school performance. Conduct during adolescence is reflected in rule following versus disruptive behaviors and rule violations at home, school, and in the community. Social competence is reflected in the adolescent’s ability to develop close and lasting relationships. Additionally, in later adolescence, additional emerging competences are found in romantic relationships and the development of job-related skills.

During the course of this longitudinal study, data were gathered across these domains and this framework of competence provides a structure within which we can examine the developmental outcomes of the children in the study. An overriding question is whether individual differences in language have greater impact on one domain than the others. In addition to examining the strength of these relationships, we are also interested in identifying when limitations in language place children at worrisome risk for later poor competences. Finally, we can ask whether there are moderators of this risk.

CAUSES OF INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Just as we needed a framework for structuring our study of the outcomes of individual differences in language development, we also needed a framework for considering the possible causes of these individual differences. Figure 1.2 provided a schematic of such causes, and we can see that there are several levels of study that could be brought to bear on this problem. In fact, there are so many causal domains and within each so many possible variables and constructs, that we could not consider a comprehensive look. As such, much of our research focused on the prominent cogni...