One of the most important concepts in cognitive psychology is that human information-processing capacity is limited. That is, people are not able to process an infinite amount of information at any one time. A number of errors that people make on cognitive tasks may reflect the limitations that are present on human information processing.

There are perhaps three classic sources for the presence of limitations on information-processing capacity. One would be Miller’s (1956) demonstration that immediate recall rarely exceeds 7 ± 2 items. A second would be the work on monitoring several simultaneous auditory inputs (i.e., shadowing; Broadbent, 1958). The third classic source would be the topic for this chapter—the partial-report paradigm developed by Sperling (I960). This paradigm illustrated the limitations that are present on visual information processing. Moreover, Sperling’s work in this area established one of the most famous and influential paradigms to be found in cognitive psychology. The account typically offered for this paradigm is breathtakingly elegant. Unfortunately, the truth as revealed by more recent findings is far more complex, as we shall see.

The Work of George Sperling

Psychologists have long been interested in the study of reading and visual perception. A natural question to ask in these areas is “How much information is a person able to see in a single glance?” A number of experimenters, dating back to the early days of psychology, addressed this question. Typically, these investigators would flash a large amount of information to subjects for so brief a time that eye movements would not be possible. Then, subjects would be asked to recall the information flashed to them. Early researchers, such as Erdmann and Dodge (1898), established that people could usually report about four stimuli (letters, numbers, or short words).

George Sperling (I960), in his doctoral dissertation at Harvard University, verified these claims. He would flash an array of numbers or letters to subjects. He found that subjects usually would report four items. It mattered little how many other items were in the array or how the items were distributed spatially. It also mattered little how long the display was flashed for, from a range of 15 milliseconds (ms: thousandths of a second) to 500 ms. In this whole-report procedure, recall seemed to be limited to around four items.

Subjects in these experiments often reported being able to see the whole array. In fact, they claimed to continue having information about the items in the array even for a time after the array was turned off. However, this information quickly faded away, so that by the time about four items had been reported, it was no longer present. Sperling’s contribution was to develop a procedure for determining whether people really did have access to more information than they were able to report with this procedure. He developed the partial-report procedure, in which he used people’s ability to recall part of the display as an indication of how much information they had about the whole display.

In his first experiment on this topic, Sperling presented two rows of letters (either three or four letters in each row). The letters were flashed briefly. Immediately after the display was turned off, a tone was sounded. The tone could be either low or high. If the tone was high, subjects were required to report the letters that had been present on the upper row of the display. If it was low, subjects were to report the letters in the bottom row. Because the tone was not sounded until after the display was turned off (and since subjects had no way of knowing what tone was going to be given until it occurred), they could only apply the tone to some form of memory for the items. The items themselves were no longer physically being shown. The most important finding was that the proportion of items reported was much higher in this partial-report procedure than in the situation where all of the items had to be recalled (the whole-report procedure). Sperling took this as evidence that the whole-report procedure led to underestimates as to the number of items that subjects were able to see in a display.

Sperling used the partial-report results to estimate the minimum number of letters that subjects must have available to them at the time the tone sounded. He calculated this estimate by multiplying the average number of items correctly recalled from the cued row by the number of rows. This estimate was considerably higher than the number of items recalled in whole report. Sperling believed that this estimate derived from a partial report was the minimum number of items available to the subject. Since subjects have to spend some time interpreting the tone and determining the correct row, some items available when the tone was presented could be lost by the time that subjects are ready to respond.

Sperling argued that subjects used a rapidly decaying trace of the visual display in this task. Some primitive memory for the items remained after the display was turned off. When asked to report the letters, subjects read them from this brief visual memory trace. During the time this trace is present, subjects have a high proportion (perhaps all) of the items available to them. However, this trace fades quickly so that it is gone by the time subjects have read out about four items. Sperling obtained evidence for the rapidly decaying nature of this trace in a later experiment where he varied the amount of time that passed between the offset of the display and the presentation of the tone. By the time a second had passed, the proportion of items recalled in the partial-report procedure was approximately the same as in the whole-report procedure. Sperling interpreted this finding to suggest that the visual trace of the display had decayed in under a second.

The partial-report task has been used by countless investigators on different populations. For example, a superiority of partial over whole report has been reported in both children (Haith, 1971) and the elderly (Gilmore, Allen, & Royer, 1986). The brief visual trace described by Sperling is typically called visual sensory memory, the visual sensory register, or, after Neisser (1967), the icon (or iconic memory). This concept now occupies a prominent place, both in our textbooks and in our theories of visual cognition.

A procedure similar to that of Sperling (I960) was developed independently by Averbach and Coriell (1961). In their procedure, an array of letters is presented for a brief period of time. At some point after the array goes off, a visual marker is presented near a location that had been occupied by a letter in the array. Subjects have to name the letter that occupied the position designated by the marker. Thus, unlike Sperling’s task, subjects only have to recall one stimulus. However, like Sperling’s task, subjects do not know what has to be reported until the signal is presented sometime after the array has been turned off. Averbach and Coriell often used a bar as their marker. They would show it under the position that had to be recalled. For this reason, the Averbach and Coriell task is sometimes called the bar-probe task.

Using their procedure, Averbach and Coriell found results that were consistent with those of Sperling. When the signal is presented immediately after the offset of the array, subjects are usually able to name the letter that occupied the cued location. It is as if subjects retain considerable information about the visual characteristics of the display. However, this information decays quickly. On trials where more time is allowed to pass between the offset of the array and the presentation of the visual marker, performance gets worse. Averbach and Coriell found that the performance of their subjects bottomed out at around 30% correct when 300 ms separated the display and the marker. Extending the time between the display and the marker past 300 ms had little effect on performance. Averbach and Coriell, in agreement with Sperling, viewed their results as evidence for a quickly decaying source of visual information.

A Model for the Partial-Report Paradigm

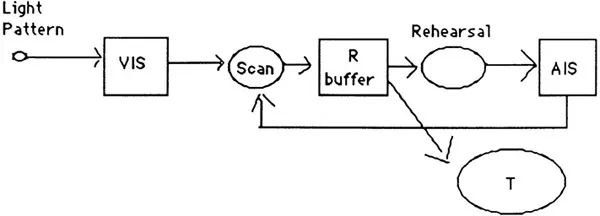

Sperling (1967) developed a complete model for how subjects performed the partial-report task. This model is presented in Fig. 1.1. Following the convention of such diagrams, mental structures are depicted in boxes and mental processes in circles. A pattern of light stimulation from the outside world enters the system. Information regarding this light pattern first enters into iconic memory (which Sperling called Visual Information Storage at the time). Iconic memory is indicated by the box labeled VIS in the figure. Information decays from this stage in less than a second. Information at this stage is precategorical; that is, there is no contact between the light patterns as they are represented in the icon and the categories contained in long-term memory. The information at this point is still raw and physical and does not contain any information about the meaning of the stimuli.

FIG. 1.1. Sperling’s (1967) model of performance in the partial-report paradigm.

Subjects extract information from the icon through the use of a rapid scanning process. It creates a visual image for each of the stimuli. This scanning process is notable chiefly for its speed. Sperling estimated that at least the first few items in the icon are scanned at a rate of 10 ms per item. (In other words, if this scan continued at this rate, subjects would be able to scan 100 items per second.) Sperling assumed that this scanning process happened in a serial fashion; that is, subjects did not process all the stimuli at once but rather scanned one stimulus at a time. Although Sperling himself had little evidence on this point, subsequent research has tended to support this conjecture (e.g., Pashler, 1984).

The images from the scanning process are still meaningless; they are simply representations of light patterns. However, they are placed in a recognition buffer. It is this buffer that “recognizes” each of the items; that is, it is in this buffer that each stimulus is given a name. Sperling (I960) had noticed that many of the errors that subjects made when identifying letters were based on the sounds of the letters. That is, subjects were more likely to confuse the letter B with the letter V than with physically similar letters, such as F. (The presence of speech-based errors in recall was studied more systematically by Conrad, 1964, and many subsequent researchers.) Thus, Sperling assumed that items were stored in the recognition buffer in terms of their sounds. More specifically, he imagined that the recognition buffer converts the visual image created by the scanner into a “program of motor instructions,” a listing of the mouth movements that would be needed to say the item aloud.

The next stage is a rehearsal stage. Subjects attempt to maintain the items by rehearsing them. Rehearsal is a much slower process than the earlier stages. Typically, it takes well over 100 ms to rehearse a single item. Rehearsal may be either aloud or silent. Sperling believed that it made no difference in memory whether items were rehearsed aloud or silently, a belief that we now know was mistaken (Crowder, 1970; this work is discussed in chap. 2).

Whether rehearsal is aloud or silent, Sperling saw the information as flowing into Auditory Information Storage, an auditory analogue of the Visual Information Store (or icon). (The terms auditory sensory memory, auditory sensory register, echo, or echoic memory have since become more popular terms for this concept.) Subjects scan this auditory store in a way analogous to the way the icon is scanned.

When subjects want to write down items they saw in the display, they have to translate the stimuli (as they are contained in the recognition buffer) into a series of muscular movements that would let them write down the correct items. Sperling professed ignorance as to the details of this stage but realized that such a process was necessary. This translation stage is indicated by the symbol T in Fig. 1.1. Information at this translation stage is now ready to be reported.

To summarize the main aspects of this model, information is stored in raw unanalyzed form in the icon. It is rapidly scanned and then maintained through rehearsal until subjects have a chance to write all the items down.

How could a model such as this be used to explain Sperling’s (I960) results? In a whole-report condition, subjects form an icon of the display, scan the icon, and recognize the items (that is, assign them the correct names). They begin rehearsing the items and writing them down. However, performance is limited at several stages. Subjects may not be able to scan and recognize all of the items before the icon has faded away. They are only able to maintain the items by rehearsing them. However, since rehearsal is such a relatively slow process, only a few items are able to be maintained this way. The result of these limitations is that subjects are only able to recall about four items or so in whole report.

When subjects are placed in a partial-report situation, they are able to use the partial-report signal to determine which locations in the icon to scan. Assuming that the signal was presented so close to the offset of the array that the icon is still present, subjects should be able to scan the necessary locations. Then, subjects will have to recognize and recall the cued items. Since there are only a few cued items, the icon should persist long enough to allow the subjects to recall a higher proportion of items than in whole report.

Although the exact details of this model did not get unanimous support, the general approach did gain general acceptance. Theoretical accounts of this sort constitute the classical explanation of performance in the partial-report paradigm.

Comments on the Concept of Iconic Memory

Alternative Procedures for the Study of Iconic Memory

In the years since Sperling’s (I960) initial research, a number of other investigators using very different approaches have supported the idea that visual stimulation persists in the nervous system for a brief time period after the end of a stimulus. Some of these approaches involved asking participants for subjective judgments as to the presence of visual persistence. These approaches are often called direct methods, because the logic for determining the presence of the icon seems far simpler and more direct than the partial-report procedure. For example, one kind of approach involves flashing a stimulus until it appears to the observer to be continuous in time (e.g., Haber, 1970; Haber & Standing, 1969; Purcell & Stewart, 1971). Another approach required asking subjects to adjust the occurrence of some signal so that it coincided with the offset of a target stimulus (e.g., Efron, 1970; Sakitt & Long, 1979). Approaches such as these have been useful in confirming the existence of iconic memory. Therefore, the concept of the icon (at least as a subjective persistence of light stimulation) is not dependent solely on evidence from the partial-report paradigm.

Initially, many researchers assumed that these direct approaches tapped exactly the same stage of visual processing that was tapped by Sperling’s partial-report paradigm. However, subsequent research has proven that assumption false. Particular emphasis has been placed on energy effects on these paradigms. The energy present in a stimulus can be manipulated by altering its luminance or duration. A large number of studies have been performed. The literature as a whole suggests that not all of these paradigms are tapping the same stages of information processing. The literature does contain enough contradictions so that two reviewers, discussing the same experiments, can reach exactly opposite conclusions (Coltheart, 1980, 1984; Long, 1980). However, it is fair to say that the partial-report paradigm is much less likely to be influenced by stimulus energy than are the direct approaches (Coltheart, 1980, 1984). The picture is complicated by the fact that energy effects do appear in the partial-report paradigm for certain combinations of target and background luminance: Under these limited conditions, the rate of decline for partial report as a function of cue delay is slower for bright displays than for dimmer ones (e.g., Adelson & Jonides, 1980; Long & Beaton, 1982). The circumstances under which partial report is affected by stimulus energy seem to be far more constrained than the circumstances under which the direct procedures exhibit energy effects. Moreover, the direct procedures often exhibit inverse energy effects; that is, the estimate for the duration of the icon decreases as the energy in the stimulus increases (e.g., Efron, 1970; Haber & Standing, 1969; Sakitt & Long, 1979). This is contrary to the findings from the partial-report paradigm where either no effect or positive effects on iconic persistence are found as stimulus energy is increased. Thus, it seems likely that performance in the partial-report procedure is not determined by the same processes as determine performance in the direct paradigms. Although these direct approaches are certainly relevant to an overall understanding of visual information processing, there is no need to consider these direct measures further in our discussion here of the partial-report procedure.

The Locus of the Icon

There has been considerable interest in determining the place in the visual system where iconic memory takes place. For example, is the icon in the eye (specifically, on the retina, that part of the eye where the visual image of a scene is projected), or does it reside deeper in the nervous system? Sakitt (1976) attracted considerable attention by suggesting that the icon represents the persistence of activity at the level of the rods, one type of receptor cell located in the retina. However, Banks and Barber (1977) presented evidence against this claim by showing that subjects could perform a partial-report experiment when required to select items on the basis of color. In this experiment, subjects were shown a display containing items in several different colors. The partial-report cue would indicate the color of the items that subjects had to report. (Although earlier investigators had used color in this task, they had not controlled all other factors carefully and were therefore not considered definitive by Sakitt, 1976). A normal partial-report curve was found, with an initial high level of recall and a gradual decline on trials where the cue was delayed. Since rod cells do not perceive color but only respond on the basis of the brightness of a stimulus, Sakitt’s proposal could not explain these results.

Banks and Barber’s (1977) findings did not end the dispute over the locus of the icon in the nervous system. Much of the subsequent research used procedures other than the partial-report paradigm, so their relevance for the present chapter is unclear. As we have seen, not all iconic procedures tap the same proc...