- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Planning Los Angeles

About this book

Los Angeles isn't planned; it just happens. Right?

Not so fast! Despite the city's reputation for spontaneous evolution, a deliberate planning process shapes the way Los Angeles looks and lives. Editor David C. Sloane, a planning professor at the University of Southern California, has enlisted 30 essayists for a lively, richly illustrated view of this vibrant metropolis.

Planning Los Angeles launches a new series from APA Planners Press. Each year Planners Press will bring out a new study on a major American city. Natives, newcomers, and out-of-towners will get insiders' views of today's hot-button issues and a sneak peek at the city to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Planning Los Angeles by David Sloane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Multiplicities/Multiple-cities

David C. Sloane

Outsiders love to hate LA, but which city, among the multiple choices, do they hate? Southern California is an economic giant that produces more than most industrial countries, while inequities abound; poorly paid, ill-housed laborers service luxury homes, elaborate gardens, and garages filled with expensive cars. Propelled by the adoption of new urbanist and smart growth reforms, LA has an increasingly vibrant street life yet is still defined by the car, reflecting the intransigent autocentric infrastructure of the 20th century. The area’s homes and streets are spectacularly beautiful, compared rhetorically through the decades to the Garden of Eden; and still, LA is a place where many poor people have to drive a few miles to find a green space where their children can play. LA is a vibrant cultural site that takes its cultural workers largely for granted, offering its enormous pool of artists fewer incentives than almost any American city. And, while regional solutions are difficult to envision here, they are even harder to enact. Given all these contradictions, almost everyone believes Los Angeles is unplanned, and cannot accept that it has a rich planning and development history. They just view Los Angeles as the iconic failure of modern city development.

Those failed relations are central to the story this book tells, and to understanding the evolving narrative of LA. Back in the 1940s, the marvelous Carey McWilliams (1973, 14), author of what is still the best introductory book on LA, wrote, “Walled off from the rest of the country by mountain ranges and desert wastes, Southern California is an island on the land, geographically attached, rather than functionally related, to the rest of America.”1

The image of LA as island is potentially trite, yet evocatively powerful. Many other authors have mimicked McWilliams’s use of it to describe Southern California’s separation and isolation; yet for me the power of the image is that it describes the region’s transience. The Southern California island continually and unevenly evolves; it does not narrate a static or linear history. For instance, LA is no longer walled off geographically or at the end of the American cul-de-sac, as University of California President Benjamin Ide Wheeler wrote in 1898 (McWilliams 1973, 134). Yet many Americans still view LA as different, a place apart from the conventional cities of the rest of the nation, partly because of our multicultures and partly because of the persistence of our suburban values.

Figure 1.1. Soccer player in Vista Hermosa Park with the backdrop of downtown’s skyscapers, 2011

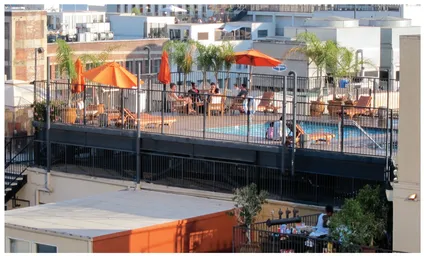

Figure 1.2. A rooftop pool above Pershing Square in downtown LA is a result of policy and planning creating a coherent strategy of downtown redevelopment.

The turn of America westward toward LA (and toward the Asian east) opened Southern California to the world, making it the prime immigrant gateway of the last half of the 20th century, diversifying its population, and internationalizing its culture—giving outsiders new reasons to be mystified by LA. As Dowell Myers and his colleagues, Steven A. Preston, and others write, the change alters our sense of LA. At one level, it created new (and to the world familiar) islands—such as immigrant enclaves in Monterey Park or Koreatown—but it also set the foundation for bridges across the islands, such as multiracial marriages and transcultural art and architecture that were signals of change (sometimes unwelcome), not only in LA but the rest of the United States. The mountains that separate California from the rest of the United States remain, and the West is still not the East (either in the United States or the world), but the distances have shrunk so that a parade celebrating Chinese New Year and altars commemorating the Day of the Dead feel almost as if they always belonged on the Californian cul-de-sac.

As work by Mike Davis (1990) and others remind us, integration comes unevenly, and usually reluctantly. As Dana Cuff (2002, 14) notes about LA mid-century home construction, “modern housing set itself apart as an island within its surroundings, to its own detriment in the end.” Building houses bracketed with front and back lawns, Angelenos moved their family recreation to the backyard and eventually put up fences to gain even greater privacy from the neighbors. After a period of ticky-tacky houses joined by open front yards and sometimes shared driveways, gated communities sprouted, especially in Orange County, further isolating and separating. Master planned communities, such as Irvine or Stevenson Ranch, could be viewed as islands floating in the larger metropolitan sea when seen on aerial photos.

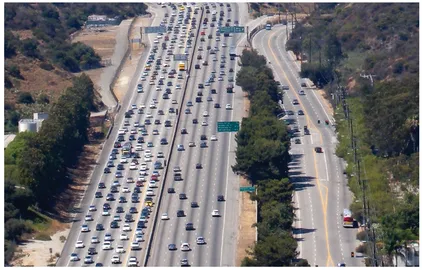

Figure 1.3. On the 405 going up the Sepulveda Pass, even cars in the southbound carpool lane just sit, waiting for a break in the traffic.

The inequalities that outsiders hate remain, since Orange County still doesn’t have an effective public transit system, and gated communities remain common throughout Southern California. Yet one can also see a turn away from that older paradigm in newer developments that are beginning more integrated, denser, and more diversified. Janis Breidenbach reminds us of the Housing Trust in LA, and Vinayak Bharne suggests Playa Vista may illustrate that even wealthier Angelenos are considering homes in denser developments with better parks and more walkable streets. The seas between the islands have not dried, but they have receded.

Finally, of course, outsiders have long viewed LA’s adoration of the car as a prime reason to simply shake their heads at the very mention of the place. Indeed, the island vision that seems hardest to shake is that of the driver snug in her car cocoon roaring down the freeway through thousands of other moving islands. This year, “Carmeggedon” became a national phenomenon as commentators comically imagined an LA without cars. The image reinforces the seeming refusal of Angelenos to live public lives, preferring their privacy and intimate, familial relations over ephemeral connections. Movie and television producers love the picture, but LA’s critics revel in it even more.

The waters may be receding even here, if very slowly. Lisa Schweitzer suggests that the victory of Measure R, while certainly flawed, could create new transit lines that might result in a new image, that of the bicyclist loading her bike aboard on the Expo Line on her morning commute. That image will not replace the cocooned driver any time soon, but it might compete with it, offering another proof of LA’s evolution.

Myths and Mythologies

Figure 1.4. A Day of the Dead altar at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, 2010

Changing people’s perception of LA, though, is difficult. We, LA’s residents, are partly at fault. As Norman Klein (1997) reminds us, LA is a city that has forgotten too much, remembers what is shiny and new, what fits with its image of itself. Of course, every city forgets what it doesn’t like and remembers the successes that burnish its image, but in LA, the newness of the city makes the forgetfulness seem more unforgiveable and the image consciousness less acceptable. The result is mythmaking at a grand scale, often with very negative results for anyone not rich and powerful.

Cities are filled with myths. Writers, storytellers, old wives, and young children spin them, leaving them behind much like the grand old houses that line the streets of West Adams, Angelino Heights, and other LA districts. Is LA a desert masquerading as a city? Does anyone actually walk anywhere? Were the original settlers “Spanish,” or Long Beach the “port of Iowa”? Telling the “truth” from the myths is difficult since they so often are at least partially true. Some, like the racist rhetoric that named the Japanese traitors and African Americans dangerous, were too easily manufactured and took too long to undermine even though they were simply lies. Others, like the GM conspiracy to end the streetcars and the CIA’s role in the crack cocaine epidemic that destroyed lives in the 1980s, have elements of truth that make them harder to complicate and retell. Either way, the stories typically belie the paradoxical nature of LA’s physical and social environment by overlooking the oppositional interrelationships that shape the city. I think we are better off engaging reality, as messy and disorderly as it is.

For instance, is LA planned, or did it, as so many seem to believe, sprawl out under the direction of greedy, thoughtless real estate developers in stark contrast to New York and the other cities of the Atlantic Coast? Todd Gish responds emphatically, “Call it ugly, call it beautiful, call it dysfunctional—but don’t call Los Angeles unplanned.” The reason is simple, as Greg Hise and William Deverell remind us: “Rather than a city that failed to plan, Los Angeles has been the subject of a surfeit of reports, studies, and proposals.” So why do so many people believe the city was unplanned? One reason was that Angelenos wanted to separate themselves from those older cities. When social worker and author Dana Bartlett (1907) hoped that LA could become “the better city,” he was imagining a place that wasn’t Boston or Philadelphia.

Residents rejected those older cities with their congested streets and disorderly housing. Cuff (2002, 28) reminds us, “From the West, the East was construed as a distinct collection of urban characteristics: besides its severe climate, the East had tenements, high densities, and an associated general overcrowding with all the commensurate health problems.” They wanted a different place—a place that (to paraphrase Bartlett) ruralized the city and urbanized the country—long before the freeway made spacious living possible.

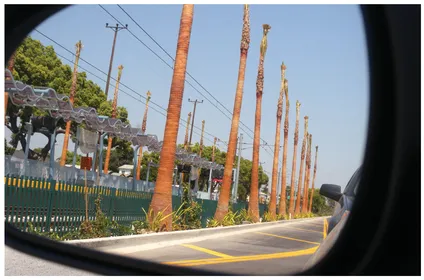

Is any other city so powerfully associated with a mode of transportation? Almost everyone accepts that LA is the ultimate sprawling autocentric city; indeed, they believe the car shaped the region, leaving individual drivers cocooned and marooned. Yet, when Bartlett wrote in 1907, the city was already sprawling out, via the nation’s most expansive streetcar system. The Pacific Electric and Los Angeles Railway lines covered more than 1,100 miles, reaching from San Bernardino to Santa Monica, Santa Ana to San Fernando, creating the skeleton of the modern metropolis. As Reyner Banham (1971, 220), the Englishman who produced one of the great books about LA, wrote, “the automobile and the architecture alike are the products of the Pacific Electric Railroad as a way of life.” Instead of the conventional myth, one might as well argue that the mass transit lines so spread out people, they had to buy a car just to get to all the places Henry Huntington (owner of the Pacific Electric) named after himself.

Figure 1.5. The vine-dripped freeways are modern LA’s equivalent of the Roman aqueducts.

The myth that LA was shaped solely by the car is so powerful that many scholars continue to accept it since the car plays such an important role in our image of the city. Architect Charles Moore (1998, 11) summarized its role in complementing the city’s art and architecture when he wrote, “If there has come to us a single image of L.A., it is doubtless the tower of City Hall, with the world’s first four-level freeway interchange nearby, dripping vines like a Piranesi view of ancient Rome.” The twin images reflect each other—City Hall, famous as the imagined home to Jack Webb’s character Sgt. Joe Friday on TV’s Dragnet, and the vines transforming the utilitarian interchange into LA’s Roman ruin of the future.

Even more alarmingly, the simple LA story that states the car isolated, fragmented, and separated the city’s residents ignores the role of the housing industry, policy makers, planners, and industry. We now know more about the home construction industry’s practices (Hise 1999), race-based social and health policy making (Molina 2006), and class-conscious neighborhood building (Cuff 2002). These forces increasingly separated Angelenos through racial covenants and single-use zoning standards, as industry located its jobs on the fringes, attracting growing populations. And they continued to do so even in the recent housing bubble, as Christian Redfearn demonstrates. Did the cars aid the physical growth of suburbs? Sure they did, but that is far from the entire story. Transportation determinism is no better an explanation than the environmental determinism of yesteryear that declared poor people would be fine if we just housed them in middle-class environments.

Marlon Boarnet, Schweitzer, and others remind us that the “multimodal” past that combined walking, biking, cars, and mass transit is also our present and future, defying the myth that LA cannot plan. Aaron Paley and Amanda Berman’s chronicle of CicLAvia, the public space extravaganza where over a hundred thousand Angelenos bicycle and walk streets closed to cars, verify the efforts to close the era of auto supremacy, as do the new transit lines Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa plans to build from Measure R.

Figure 1.6. The new LA Metro Expo Line on Exposition Boulevard. Long home to the famed “red cars” of the Pacific Electric, the boulevard is once again a transit corridor.

These myths feed the ultimate LA planning myth, the one that declares that LA is the anti-city. In her majestic Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), Jane Jacobs viewed LA as the antithesis to her beloved Lower Manhattan, and relied on it as an example of the modern planning she hated. She railed against the city’s reliance on the philosophy of “togetherness” that demanded shared values and did not appreciate the simpler, ephemeral relationships of public life. Even before Jacobs, LA had become the iconic representation of sprawl, a message driven home by William Whyte’s (1958) evocative metaphor of bulldozers from LA meeting those from San Bernardino somewhere many miles east of downtown. After Jacobs’s initial attack, other commentators followed suit, especially during the early years of the antisprawl campaign and the birth of new urbanism. LA became the capital of sprawl, infamous for its freeways and suburban lifestyle. Was LA a city? Yes. Was it a place that embraced urbanity and valued public life? No.

Scholars have exploded the popular image of LA as a collection of (bedroom) suburbs in search of a city. Most prominently, Greg Hise showed in Magnetic Los Angeles (1999) that many suburbs, such as Westchester and Pacoima, were constructed not for their bedrooms but for their jobs, as industrial suburbs with housing and services. Becky Nicolaides (2002) and others chronicled the rise and complexity of vibrant places and commercial activities ranging from the blue-collar neighborhoods in Long Beach and San Pedro to the suburban homesteads of the San Fernando and San Gabriel valleys.

When Breidenbach reminds us that a majority of LA households have never owned their homes, a central myth of LA’s popular story crumbles. How can the majority be renters in a city where home building ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: History of Planning

- Chapter 3: Evolving Demographics

- Chapter 4: Land-Use and Environmental Policies

- Chapter 5: Mobility and Infrastructure

- Chapter 6: Parks and Public Space

- Chapter 7: Economic Development

- Endnotes

- References

- Contributors

- Credits