- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studying the Novice Programmer

About this book

Parallel to the growth of computer usage in society is the growth of programming instruction in schools. This informative volume unites a wide range of perspectives on the study of novice programmers that will not only inform readers of empirical findings, but will also provide insights into how novices reason and solve problems within complex domains. The large variety of methodologies found in these studies helps to improve programming instruction and makes this an invaluable reference for researchers planning studies of their own. Topics discussed include historical perspectives, transfer, learning, bugs, and programming environments.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section III:

Learning Programming Concepts

Given that programming is to be taught in the schools, the next questions to address are what programming concepts should be taught and how should the concepts be taught so that students can effectively learn the material? The papers in this section examine the following six concepts commonly presented in introductory programming classes:

Each paper presents the results of empirical studies that illuminate what novices are actually learning (or failing to learn) when taught these concepts. The final paper in this section discusses some of the important differences in problem-solving and learning styles that exist between novice programmers.

Mayer's paper examines the instructional techniques of providing a concrete model of the computer to the novices as well as encouraging the novices to put technical information into their own words. The results of Mayer's studies show that, under certain conditions, both of these techniques can have a positive impact on the students' ability to solve new problems that were not explicitly taught. A further discussion of concrete models or "notional machines" can be found in the paper by du Boulay, O'Shea, and Monk in the section Designing Programming Environments in this volume.

In the next paper, a "fill in the blanks study is used to understand the nature of novices' conceptions about the use of programming variables. Samurcay finds, among other things, that using variables in contexts that are similar to previously learned domains (e.g., X = 0 makes sense as an algebraic equation) is easier for novices than using variables in contexts that somehow violate those previously learned domains (e.g., COUNT = COUNT +1 does not make sense as an algebraic equation). Sarnurcay's observations about the influence of previously learned domains agree with Hoe's observation that: "the construction of a program is never done from tabula rasa." Hoe's study identifies important similarities and differences between nonprogramming use of conditional reasoning and the use of conditionals in programs. In their paper in the section Bugs, Bonar and Soloway examine how pre-programming knowledge can lead to various bugs in novice programs.

Three papers in this section deal with the topics of looping and recursion. The Soloway, Bonar, and Erhlich paper finds that programmers are more likely to generate correct programs when the looping constructs in the language they are using more closely match the "natural" looping strategies subjects prefer. Kahney's paper explores many alternative mental models of recursion that novices adopt, and finds that novices tend to incorrectly view recursion as a form of looping. Kahney uses excerpts from thinking-aloud protocol data as evidence for the alternative models of recursion. Kessler and Anderson performed experiments that found that learning to write iterative functions first helped novices later learn to write recursive functions, but not vice versa. Analysis of thinking-aloud protocol data revealed that if recursion was taught before iteration the novices' poorly formed mental models of recursion actually interfered with the novices' ability to learn iteration second. In the section Bugs, Kurland and Pea examine in detail the types of bugs novices make when learning about the concept of recursion.

Perkins and his colleagues at the Harvard Educational Tecnnoiogy Center are concerned with the question "Why is there such a wide range in competence between novice programmers?" Some students take to programming like ducks to water, while others seem almost totally lost. Their research traces much of the variability to different patterns of learning that each individual brings with them to the programming task. Specifically, they identify two different learning styles: stoppers and movers. Stoppers tend to disengage from the programming task at the first sign of trouble, whereas movers will begin tinkering with a partial solution. Perkins suggests that one way to help stoppers become movers is to encourage them to use neglected strategies (such as tinkering, close tracking, and problem decomposition) when the stopper hits a problem, instead of simply disengaging.

This section presents a wide range of findings on what novices are learning when they are taught about programming concepts. In addition to the specific findings, the research presented here is interesting because the results were obtained using such a diverse set of experimental procedures (e.g., "fill in the blanks" studies, controlled experiments, thinking-aloud protocols, clinical interviews, etc.).

7

The Psychology of How Novices Learn Computer Programming

RICHARD E. MAYER

Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

This chapter examines the current state of knowledge concerning how to increase the novice's understanding of computers and computer programming. In particular, it reviews how advances in cognitive and educational psychology may be applied to problems in teaching nonprogrammers how to use computers. Two major instructional techniques are reviewed: providing a concrete model of the computer and encouraging the learners to actively put technical information into their own words.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the question, "What have we learned about how to increase the novice's understanding of computers and computer programming?" In particular, it reviews ideas from cognitive and educational psychology that are related to the problem of how to teach nonprogrammers to use computers. Since people who are not professional programmers will have to learn how to interact with computers, an important issue concerns how to foster meaningful learning of computer concepts by novices.

Meaningful learning is viewed as a process in which the learner connects new material with knowledge that already exists in memory [Bran79]. The existing knowledge in memory has been called a "schema" and the process of connecting new information to it has been called "assimilation." However, there is not yet agreement concerning the specific mechanisms that are involved in "assimilation to schema" [Ande77, Ausu77, Bart32, Kint74, Mins75, Rume75, Scha77, Thor77],

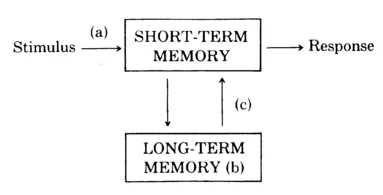

Figure 1 provides a general framework for a discussion of the process of meaningful learning (or assimilation to schema) of technical information [Maye75a, Maye79a]. In the figure the human cognitive system is broken down into

- short-term memory—a. temporary and limited capacity store for holding and manipulating information;

- long-term memory—a permanent, organized, and unlimited store of existing knowledge.

New technical information enters the human cognitive system from the outside and must go through the following steps for meaningful learning to occur:

- (1) Reception. First the learner must pay attention to the incoming information so that it reaches short-term memory (as indicated by arrow a).

- (2) Availability. Second, the learner must possess appropriate prerequisite concepts in long-term memory to use in assimilating the new information (as indicated by point b).

- (3) Activation. Finally, the learner must actively use this prerequisite knowledge during learning so that the new material may be connected with it (as indicated by arrow c from long-term memory to short-term memory).

Thus, in the course of meaningful learning, the learner must come into contact with the new material (by bringing it into short-term memory), then must search long-term memory for what Ausubel [Ausu68] calls "appropriate anchoring ideas" or "ideational scaffolding," and then must transfer those ideas to short-term memory so they can be combined with new

FIGURE 1 Some information processing components of meaningful learning. Condition (a) is transfer of new information from outside to short-term memory. Condition (b) is availability of assimilative context in long-term memory. Condition (c) is activation and transfer of old knowledge from long-term memory to short-term memory.

incoming information. If any of these conditions is not met, meaningful learning cannot occur; and the learner will be forced to memorize each piece of new information by rote as a separate item to be added to memory. The techniques reviewed here are aimed at ensuring that the availability and activation conditions are likely to be met.

The goal of this paper is to explore techniques for increasing the novice's understanding of computer programming by exploring techniques that activate the "appropriate anchoring ideas." Two techniques reviewed are (1) providing a familiar concrete model of the computer and (2) encouraging learners to put technical information into their own words. Each technique is an attempt to foster the process by which familiar existing knowledge is connected with new incoming technical information. For each technique a brief rationale is presented, examples of research are given, and an evaluative summary is offered.

1. Understanding of Technical Information by Novices

1.1 Definitions

For our present purposes understanding is defined as the ability to use learned information in problem-solving tasks that are different from what was explicitly taught. Thus understanding is manifested in the user's ability to transfer learning to new situations. Novices are defined as users who have had little or no previous experience with computers, who do not intend to become professional programmers, and who thus lack specific knowledge of computer programming.

1.2 Distinction Between Understanding and Rote Learning

The Gestalt psychologists [Wert59, Kato42, Kohl25] distinguished between two ways of learning how to solve problems — rote learning versus understanding. With respect to mathematics learning, for example, a distinction often is made between "getting the right answer" and "understanding what you are doing."

In a classic example Wertheimer suggests that there are two basic ways to teach a child how to find the area of a parallelogram [Wert59]. One method involves dropping a perpendicular line, measuring the height of the perpendicular, measuring the length of the base, and calculating area by use of the formula, Area = Height × Base. Wertheimer calls this the "rote learning" or "senseless" method, because the student simply memorizes a formula and a procedure. The other method calls for the student to explore the parallelogram visually until he sees that it is possible to cut a triangle from one end, put it on the other end, and form a rectangle. Since the student already knows how to find the area of a rectangle, the problem is solved. Wertheimer calls this method "structural understanding" or "meaningful apprehension of relations," since the learner has gained insight into the structure of parallelograms.

According to Wertheimer, if you give a test involvi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Section I Early Work

- Section II Transfer

- Section III Learning Programming Concepts

- Section IV Difficulties, Misconceptions, and Bugs

- Section V Designing Programming Environments

- Credits

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Studying the Novice Programmer by E. Soloway, J. C. Spohrer, E. Soloway,J. C. Spohrer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.