- 470 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Nature of Expertise

About this book

Due largely to developments made in artificial intelligence and cognitive psychology during the past two decades, expertise has become an important subject for scholarly investigations. The Nature of Expertise displays the variety of domains and human activities to which the study of expertise has been applied, and reflects growing attention on learning and the acquisition of expertise. Applying approaches influenced by such disciplines as cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence, and cognitive science, the contributors discuss those conditions that enhance and those that limit the development of high levels of cognitive skill.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Nature of Expertise by Michelene T.H. Chi,Robert Glaser,Marshall J. Farr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | Expertise in Typewriting |

INTRODUCTION

The other chapters in this book are concerned primarily with expertise in mental tasks. Even though an expert waiter or radiologist may use motor skills, such as speech and handwriting, the motor skills themselves are not of direct interest to most investigators. This chapter, on the other hand, is concerned with the acquisition and performance of the motor skill of typewriting. Motor skills provide a unique psychological insight, because they are the direct, concrete product of fhe large amount of mental processing required for the planning, coordination, and control of actions. From a practical standpoint, motor skills offer a unique advantage to the scientist studying expertise. Most of the interesting events in mental skills go on inside the head, and are hidden from our view. The scientist must make indirect inferences about these mental events from such data as reaction times and verbal protocols. In contrast, the normal performance of a motor skill produces an externally observable sequence of events that are directly related to the task.

It is clear from anatomical studies of the brain, and observation of patients with brain injury, that even in humans a large portion of the brain is involved in the performance of motor skills. Some motor skills, such as walking and speech, develop in childhood as the motor system itself develops, and are normally acquired without special effort. Other motor skills, such as juggling, playing piano, or flying an airplane, although based on existing perceptual and motor skills, require special instruction to acquire and gain expertise. Expertise in typewriting belongs in the latter class. Prospective typists spend hundreds of hours in classes and at practice before they are expert enough to be employed. In fact, when typewriters were first manufactured, they were operated by the hunt-and-peck method. It took at least another 20 years before it was generally realized that it was even possible to type using all ten fingers and without looking at the keyboard.

A typical professional typist has accumulated an incredible amount of practice. A conservative assumption would be that a typist averages 50 words per minute (wpm) for 20 hours per week. Over the course of 10 years, that would amount to 150 million keystrokes or 25 million words. In those 10 years, this hypothetical typist would have typed the word the 2 million times, and typed a common word like system 10,000 times. The speed of professional typists is also quite remarkable. A typing rate of 60 wpm corresponds to an average of five keystrokes per second. The fastest typists I have studied maintain an average of more than nine keystrokes per second over the period of an hour.

ACQUISITION OF TYPEWRITING

In common with the other tasks described in this book, it takes people a surprisingly long time to become expert typists. The performance norms listed by West (1983, p. 346) give the following median typing speeds for students: 38 wpm for students completing the first year of high school typing, 44 wpm for students completing the second year of high school typing, and 56 wpm for students at the end of business school training. (These scores are gross words per minute, with no correction for errors.) The surprising finding is that after 3 years of practice, the median graduate of business school is just barely meeting minimal employment standards. Estimating 5 hours of practice per week and 40 weeks per year, in 3 years a student would have accumulated about 600 hours of practice on the typewriter.

It's instructive to contrast the time required to become an expert typist with the time required to learn to fly an airplane, which is generally acknowledged to be a reasonably difficult motor skill. A private pilot's license requires only 35 hours of flight time. Even combat pilots in the U.S. Air Force have only 300 to 350 hours flying time plus another 75 hours of simulator training when they report to their operational squadron (D. Lyon, personal communication, August, 1983). Of course there are probably motivational and aptitude differences between pilot trainees and typing students, but the similarity in acquisition times makes clear that learning to type at the professional level is not an easy task.

Like other motor skills, typewriting, once acquired, is remarkably resilient. In a classic series of motor learning studies, Hill (1934, 1957; Hill, Rejall, & Thorndike, 1913) recorded data from three month-long efforts to learn typewriting that were separated by lapses of 25 years. Hill found significant savings of skill at the beginning of the second and third learning efforts, despite the intervening 25 years between efforts. Salthouse (1984) studied the performance of professional typists ranging in age from 19 to 68 years. He measured performance of the typists on a battery of tasks, including a forced-choice reaction time task on the typewriter keyboard and a normal transcription typing task. Salthouse found that performance in the transcription typing task was not correlated with age, even though performance on supposedly similar motor tasks, such as tapping speed and forced-choice reaction time, showed the usual decline with age.

COMPARISONS OF EXPERT AND NOVICE TYPISTS

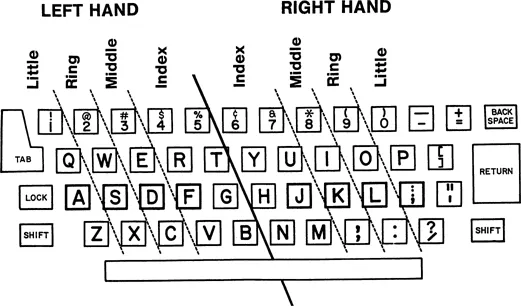

How do expert typists differ from novices? I've examined this question by comparing the performance of student typists and professional typists. For most of the studies reported here, the typists were asked to transcribe normal prose texts for about an hour. They typed on an electronic keyboard with a layout and “feel” similar to the IBM Selectric keyboard (Figure 1.1). Keystrokes and the corresponding times were recorded by a microcomputer with a resolution of 1 msec. The typists' finger movements were recorded on videotape.

The student typists were volunteers from the first semester typing class at a local high school. They came to the laboratory once a week between the fourth and eighth weeks of class. The expert typists were professional typists recruited from the university and from local businesses. Most of the experts were typical office secretaries, but a special effort was made to recruit a few very fast typists.

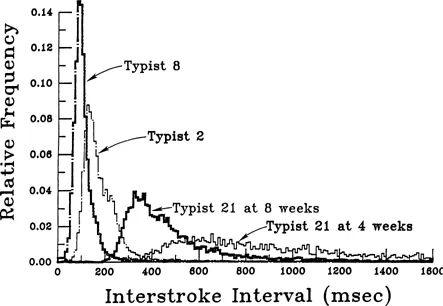

Faster Interstroke Intervals

The first measure of keystroke timing examined was the distribution of interstroke intervals. Figure 1.2 illustrates the range of distributions found among typists, showing the distribution of interstroke intervals for a student (Typist 21) at two points in time, a typical office typist (Typist 2), and an unusually fast typist (Typist 8). This figure also demonstrates the most obvious difference between novice and expert typists: experts type faster than novices. The typing speed of the students participating in this study ranged from 13 wpm for one student in the fourth week of class to 41 wpm for another student in the eighth week of class. (The typing speeds reported in this chapter are gross words per minute, with no correction for errors. A word was taken to be five characters, including spaces.) The typing speed of the expert typists ranged from 61 to 112 wpm. In addition to being faster, the expert typists generally had a much lower error rate than the student typists.

STANDARD QWERTY KEYBOARD

FIGURE 1.1 The layout of the keyboard used in these studies. This is the standard American “qwerty” keyboard and is identical to the layout of the IBM Selectric typewriter.

FIGURE 1.2 The distribution of all interstroke intervals for Typist 21 after 4 weeks (13 wpm) and 8 weeks (25wpm) of typing class, Typist 2 (66 wpm), and Typist 8 (112 wpm).

How does the performance of the expert typists compare in detail with the performance of the student typists? Is expert performance simply a speeded-up version of student performance, or do qualitative changes in performance occur during acquisition of typing skill? As one approach to these questions, consider the simple movement required to type two letters in sequence with the same finger, such as de. The de interstroke intervals of experts were more than twice as fast as the de interstroke intervals of students. There are only three basic ways that an expert could type the e more quickly: (a) the finger movement to type the e could start earlier; (b) the finger could travel a shorter path; (c) the finger could move faster.

To investigate this issue, I have examined the videotape records of the expert and student typists when typing the digraph de. The study included eleven expert typists ranging in speed from 61 to 112 wpm, and eight student typists in the seventh week of their typing class, ranging in speed from 17 to 40 wpm. For each typist, the 10 instances of de (5 instances in the case of student typists) with interstroke intervals closest to that typist's median de interstroke interval were selected for study. For each instance, the position of the left-middle fingertip was digitized on the videotape recording and the trajectory was calculated in three-dimensional space. The time of the first visible movement toward the e key was determined from a plot of the finger trajectory. Three measures were calculated for each trajectory: (a) the lag time – the time from the initial depression of the d key until the first visible movement toward the e on the top row; (b) the path length – the distance moved by the fingertip from the beginning of the movement until the e keypress; (c) the average speed of movement – the path length divided by the movement time. The results are shown in Table 1.1. Surprisingly, the mean path length of the students was slightly shorter than that of the experts, so the experts were not typing the e more quickly because of a shorter path. Instead, the experts started their finger movements with a shorter lag time after pressing the d (accounting for about 60 msec of the difference in interstroke intervals), and moved their fingers about twice as fast (accounting for the remaining 150 msec).

This picture develops an interesting twist when the data are examined for each group separately. An analysis of the correlations between the interstroke interval and the three measures (See Table 1.2) showed that the speed of finger movement was the primary determinant of the interstroke interval for ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- In Memoriam

- Overview

- Introduction: What Is It to Be an Expert?

- Part I Practical Skills

- Part II Programming Skills

- Part III Ill-defined Problems

- Part IV Medical Diagnosis

- Author Index

- Subject Index