- 538 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Science for Environmental Management

About this book

Environmental Science for Environmental Management has quickly established itself as the leading introduction to environmental science, demonstrating how a more environmental science can create an effective approach to environmental management on different spatial scales. Since publication of the first edition, environmentalism has become an increasing concern on the global political agenda. Following the Rio Conference and meetings on population, social justice, women, urban settlement and oceans, civil society has increasingly promoted the cause of a more radical agenda, ranging from rights to know, fair trade, social empowerment, social justice and civil rights for the oppressed, as well as novel forms of accounting and auditing.

This new edition is set in the context of a changing environmentalism and a challenged science. It builds on the popularity and applicability of the first edition and has been fully revised and updated by the existing writing team from the internationally renowned School of Environmental Science at the University of East Anglia.

Environmental Science for Environmental Management is an essential text for for undergraduate students of environmental science, environmental management, planning and geography. It is invaluable supplementary reading for environmental biology and environmental chemistry courses, as well as for engineering, economics and business studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environmental Science for Environmental Management by Timothy O'Riordan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Environmental science on the move

Science does not need qualifiers like ‘good’ or ‘green’, or suffixes like ‘ism’. Adding the -ism is designed simply to bring science down to the level of the pseudo sciences such as Marxism or Creationism. People who do so think it a ticket of entry: actually it is a rejection slip.

(Alex Milne writing in the New Scientist, 12 June 1993)

Do not underestimate the difficulties of interdisciplinarity. The more specialities we try to fit together, the greater are our opportunities to make mistakes -and the more numerous are our willing critics. Science has been defined as a self-correcting system. In this struggle, our primary adversary should be ‘the nature of things’.

(Garrett Hardin on the 30th anniversary of his ‘Tragedy of the commons’article, writing in Science, 1 May 1998, 683)

Topics covered

- Science and culture

- Science and policy

- Disciplinarity, multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity

- Precautionary principle

- Civic science

- Knowledge and feeling

A Challenge to Science

Alex Milne speaks for many scientists who see their culture threatened by a wave of populist criticism. The claim of the non-conformists is that the established ways of conducting science act against sensitive and precautionary environmental management by reflecting and reproducing the elitist and exploitative aspects characteristic of all instruments of power. For example, Brian Wynne and Sue Meyer (1993) echo the environmental activist when they argue that research seeking a high degree of control over the system being studied, and which enables precise observations of the behavioural correlations between a small number of variables, draws the regulator into examining only those phenomena where cause and effect can be either proved or shown to be reasonably unambiguous.

This practice tends to place the regulator on the defensive. There may be a great number of intercorrelating factors that are not measured with equivalent diligence, due to lack of resources or inadequate recording equipment. But in democratic political cultures, the regulator has to justify the level of protection being sought. A challenge by a prosecuted discharger can result in a costly and time-consuming appeal. The courts tend to operate on provable and substantive evidence, so clever and wealthy defendants can afford to wheel in a scientist who can throw doubt on many alleged chains of cause and effect. It is tempting for the regulator to play safe and determine the environmental standard or the permitted level of discharge on the basis of the evidence that can stand up in court. That in turn will rely on the conventional scientific method. Hence the very essence of the scientific technique becomes a political weapon in the legal culture of appeal and ministerial determination of environmental quality.

Science is value-laden, as are the scientists who practise their trade. That is to be expected, though it is not always recognised. We shall see that the process of peer review is designed to iron out any obvious ideological wrinkles. More important is the belief that the practice of science may reinforce a non-sustainable economic and social culture. Because we do not know where the margins of sustainability are, as pointed out in the next chapter, the scientific approach may provide a justification for pushing the alteration of the planet beyond the limits of its tolerance. Even by playing safe, the scientific approach may, quite unintentionally, create a sense of false security over the freedom we have to play with the Earth. The critique is therefore directed at the role and self-awareness of science in a world that is grappling for the first time with seeking to restrain human aspiration and imposing global obligation of self-fulfilling private and public enterprise. Until now those qualities have been the very essence of progress and material security To challenge them requires boldness and a cast-iron justification.

Science as culture

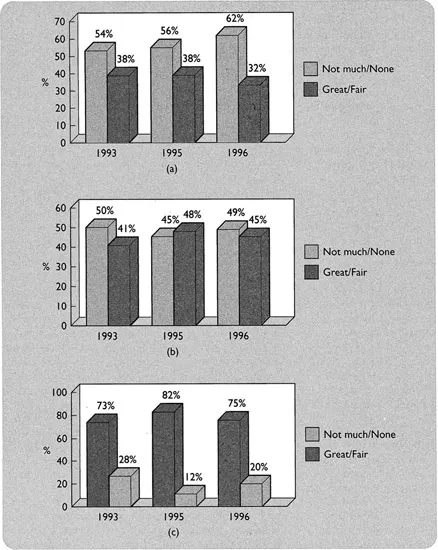

In a revealing public opinion poll, MORI (Worcester, 1998) asked a representative sample of the British population how much confidence they had in scientists associated with particular organisations. The results are presented in Figure 1.1. Over half said that they had either no confidence or not much confidence in scientists working for government, and almost the same proportion felt the same way about scientists working for industry. More to the point, the trust rating for government-funded and government-based scientists has fallen steadily over the past three years. Yet the same sample had almost twice as much confidence in scientists working for environmental organisations. In a separate study, Marris et al. (1998) found that about 60% of a sample of Norwich (UK) residents trusted scientists linked to independently financed

Figure 1.1: Responses, in 1993, 1995 and 1996, to the question ‘How much confidence would you have in what each of the following have to say about environmental issues? (a) Scientists working for government; (b) scientists working in industry; (c) scientists working for environmental groups.’ Responses: A great deal/A fair amount/Not very much/None at all/Don’t know (omitted).

Source: MORI Business &The Environment Study.

bodies. This study reviews this evidence in a wider context in O’Riordan et al. (1997). The implications of these findings will also be analysed in Chapter 17.

What we witness here is the recognition by the general public of what students of scientific knowledge have argued for many years, namely that judgements about science are influenced by views on the setting and purpose of their work, and that scientific knowledge is not ‘objective’ at all. It is socially constructed by a host of rules, norms, networks of bias and expectation, and peer group pressures that define approval and disapproval, conformity and non-conformity. To be specific, science is judged by most scientists in one manner, but in very different ways by those whom they hope to serve and to inform. We shall see that processes of judgement are institutionally framed and value-laden.

Jasanoff and Wynne (1998, 16-19) provide the most succinct summary of this relationship:

Knowledge and the technology it sustains are produced through complex forms of communal work by scientists and technical experts who engage with nature in interaction with their multiple audiences of sponsors, specialist peers, other scientists, consumers, interpreters and users. (Jasanoff and Wynne, 1998, 16-17)

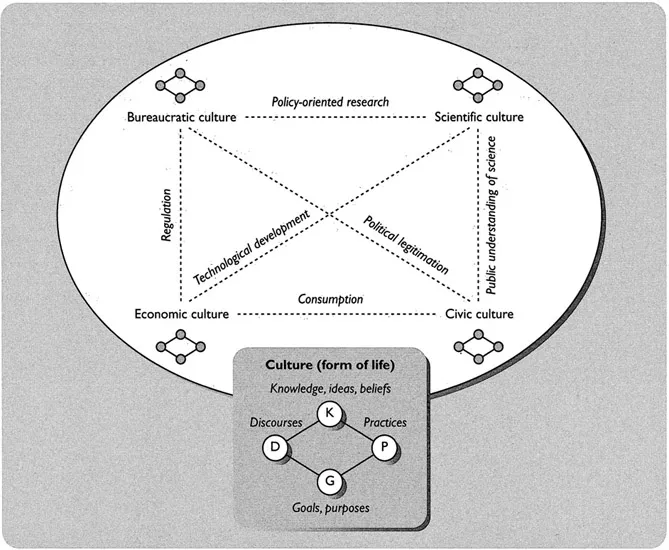

Figure 1.2 outlines this view, known as the constructivist approach to science and technology. No fact is independently verifiable outside some set of constructed and agreed rules. Because these rules change, no scientific endeavour is absolute. Even the practice of replication is a matter for agreement and consensus-seeking. We shall see in the chapters that follow that apparently straightforward matters as measurement involve ‘norm-framed’ choices. For example, how many samples of rainfall must be made in the North Sea to ‘prove’ a certain level of particulate air pollution from, say, volatile organic compounds? The answer lies in what peer groups expect, though the precise methodology that is acceptable may vary from peer group to peer group, and will certainly be influenced by the improving quality of instrumentation and measurement. How many sensors are required on the ocean surface before the character of a gyre can be proven? The answer, in part, depends on the size of the research grant, and the relative wealth of the research funders. Big international programmes absorb big money for monitoring equipment. Yet monitoring is not attractive as a research activity and rarely picks up the best scientists and core funding. As Meredith and his colleagues note in Chapter 8, the future of ocean science may be influenced by political decisions over the scale of monitoring required in the coming decades.

Data on suicides depends on the social and political context of the suicide. Suicide in prisons will be recorded differently from suicides among sufferers of AIDS. Suicides from alleged organo-phosphate contamination from sheep dip will be measured, and interpreted, differently from suicides from depression caused by unemployment. All phenomena being measured are not independent of a context, a meaning, a statistical rule or a peer review as to acceptable methodological norms. If a researcher reaching the end of PhD fieldwork finds a run of ‘quirky’ data, what does he or she do? Ignore them? Suppress them? Ask for more funding but lengthen the PhD process? Recalibrate the instruments? The answers will reveal a lot about the inner pressures of scientific conformity or unconformity. For the young researcher, these are important observations. We shall discuss the application of ‘third dimension power’ in Chapter 3. This is the encapsulation of the outlooks regarding ‘good science’ by subordinates by those who wish to order such young values in their own interests. The young researcher seeks to please and impress peer groups: to step out of line too early is not deemed wise. Conformity may, however, be regretted, especially if interdisciplinarity is the goal.

Figure 1.2: Knowledge generation and institutional framing. Any knowledge is mediated through a series of cultures, but most notably scientific, bureaucratic, civic and economic cultures. These frame both ‘facts’ and ‘interpretations’ of calamity and hence responsibility. Culture, in this context, involves knowledge, discourse (i.e. agreed interpretations of contentious issues), practices and goals (or idealised reasons for being and acting). The dashed lines indicate the nodes of scientific interaction with the civil society, in policy, regulation, public understanding and attitudes to lifestyles. This constantly changing set of relationships is continually being reconstructed, hence the term ‘constructionist’ view of science.

Source: Jasanoff and Wynne (1998, 17).

Science and policy

In a controversial article., Representative George Brown Jr (1997, 13), the ranking Democratic member of the US House of Representatives, claimed that environmental science ‘has been distorted to serve political purposes’. His point was that ideological critics of tough and costly regulatory rules sought to prove to a responsive Republican majority that the science justifying many of these high regulatory standards was promoted by the mindset of ideological liberals. These people, he commented, together with ‘an unholy alliance of scientists eager to reap the benefits of federal research funding and environmentalist groups determined to support a political agenda that systematically exaggerated environmental problems’, are regarded by the Right as dangerous subversives. Science, he warns, is simply not seen as independent or neutral. Rather, it is regarded by those who dislike ‘big government’ as self-serving and arrogant. We shall see in Chapter 7 that it has taken the US Congress over a decade to accept that there is a global warming ‘problem’, and even now, a sizeable number in both Houses of Congress remain unconvinced for many of the reasons that Congressman Brown cites. This does not make constitutional ratification of the Kyoto agreement easy.

Brown argued that there was no evidence of scientific misconduct, and that the best environmental science was ‘being conducted in an objective and apolitical manner, consistent with the traditional norms of scientific integrity’ (Brown, 1997, 14). On the other hand, the critics, often funded by lobbies of special interests, failed to confront scientists on their own ground of published peer review, and sought to present their views in opinion pieces aimed at policy makers, the media and the general public. We shall see in Box 7.7 that this is a particularly controversial point in climate science.

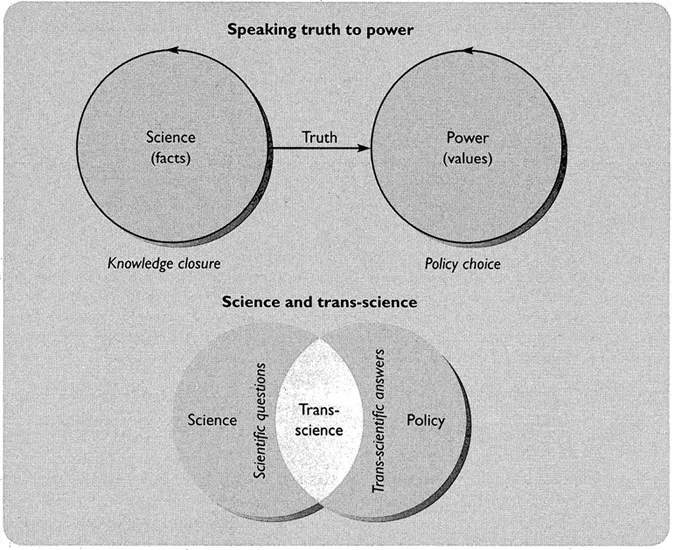

Figure 1.3 looks at the changing interpretations of science and policy. Note the steady shift from a ‘hands off’ approach to one which increasingly involves ethical and judgemental issues, formerly the domain of politicians acting alone. This evolution is by no means universally shared amongst the scientific and policy practitioners. Both prefer to ‘educate’ the public from their particular perspectives.

Figure 1.3: Views of the relationship between scientific knowledge and public policy. Conventionally science is seen as providing the necessary facts for policy makers to select and interpret. Subsequently scientists recognised that facts and judgemental bias are interconnected, and the notion of trans-science was born. Subsequently a more interactive version, namely civic science, became the vogue.

Source: based on Jasanoff and Wynne (1998, 8).

At stake here is who decides what is ‘sound science’, or ‘good grounds’ for early political action. According to Brown, the politicians on the libertarian Right see in science a justification for predetermined policy positions, Productivity in science effectiveness terms is regarded as the ability to alter public opinion by persuasion rather than by knowledge. Science could become funded by political fad rather than genuine enquiry. Congressman Brown advocated even more rigorous peer review of all scientific evidence, full disclosure of funding sources,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- List of journals

- 1 Environmental science on the move

- 2 The sustainability debate

- 3 Environmental politics and policy processes

- 4 Environmental and ecological economics

- 5 Biodiversity and ethics

- 6 Population, adaptation and resilience

- 7 Climate change

- 8 Managing the oceans

- 9 Coastal processes and management

- 10 GIS and environmental management

- 11 Soil erosion and land degradation

- 12 River processes and management

- 13 Groundwater pollution and protection

- 14 Marine and estuarine pollution

- 15 Urban air pollution and public health

- 16 Preventing disease

- 17 Environmental risk management

- 18 Waste management

- 19 Managing the global commons

- Index