![]()

The Force

of the Body

![]()

The Competent Body

The positions our bodies assume, the gestures they make, and the operations they perform are not responses to the objective representation of the material universe elaborated by scientific thought. Our sensory-motor organisms respond to the environment as they perceive it. To understand why a spider does not respond to a dead fly put in its web, but crouches and leaps when a vibrating tuning fork of a certain kind touches its web, we have to view the spider not as a material mass reacting to all the forces our physico-chemical representation of the environment identifies, but as an organism capable of activating itself in certain organized ways in response to the range and structure of its environment as its own perception presents that environment. When we sit down on a park bench or wander through the azalea plantings in bloom, our movements are not spasmodic reactions to clouds of atoms, nor to masses of sensations scintillating in our minds, but responses to the shapes in our perceptual field. The physicist who conceives material things as electromagnetic fields perceives the contours and solidity of the chair he reaches for.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception1 worked out a vocabulary designed to describe the structures and organization of the environment as our sentient bodies perceive it. Our bodies maintain a gait in walking and a rhythm in acting, they assume postures and initiate coordinated manipulations which shift the perceived field, alter the range and relief of the perceived forms that field contains, and respond to those forms. The phenomenology of perception requires a vocabulary proper to describe body postures and movements responding to perceived landscapes and gestures and operations responding to perceived objectives. Merleau-Ponty’s work describes our bodies, not as material objects of nature agitated by stimuli, but as organisms capable of perceiving and activating themselves in organized ways—our bodies as structures of perceptual and behavioral competence.

Things

What is it that we perceive? We perceive things—configurations against a background. From time to time, it is true, perceptions of radiance, darkness, fog, sky, rumble, or stench get mentioned in Merleau-Ponty’s text, but they are moments of instability or nonachievement, not the normal case. Merleau-Ponty finds that there is a finality in perceptual consciousness; perception is a positing.of things. A dark tone marginally visible, then shifted to the focal center of the visual field, then brought out of the shadow is not simply appearances that succeed one another; there is a sense of the right lighting, the real color, and the real size and shape of something explorable. What determines the real and the true and the right is the possibility of a thing taking form and stabilizing before us. And there is a normative coherence, a consistency in the evolving zone of perception. Our perception opens, not upon one shape that replaces and effaces another, but upon a field of coexisting, compossible things. That is why, despite the fog, despite the darkness, despite the rumble, Merleau-Ponty can say that a figure against a field is the essence of, the very definition of, perception.2 We cannot explain the apparition of things by a subject of the perception which collates or synthesizes its sensations; it is instead the thing that polarizes and focuses the various sensory surfaces and organs of the perceiving subject.

Things are wholes which involve a multiplicity of parts or aspects. Phenomenology of Perception argues that a perceived thing has the constitution of a gestalt. There are different sensible aspects, and each does something in its own place and moment to contribute to the composition of the thing. But they do not exist outside of the whole—which partitions them, gives them their role, and makes them function. The soap molecule we conceptually identify does not exert a force of cohesion in the directions it does to occupy its present place when it is outside of the soap bubble. And the perceived red of the brick is the red it is only when involved with this solid texture, this light, this expanse of more red or of other colors. We cannot say what this red is, or see it, outside of this complex of the colors that intensify it, contrast with it, reverberate with it, the textures that modulate it, and the form that molds it, condenses it, or fragments it.

What holds the different sensible elements of a thing together is neither simple extrinsic relations of juxtaposition, nor some universal factor also intuited along with them, nor some ideal factor to which they would be predicated. Their unity is not intuited, conceived, or posited apart from them; it is sensible and perceived with them and in them. It is, then, not an essence in the sense of an invariant nucleus of traits. It is also not an order or a system or a law that is instantiated in them, but of itself is universal. Merleau-Ponty introduces the concept of a “sensible essence.”3 It designates the way each element in a perceived thing leads to, involves, implicates, reflects, and is in its own register equivalent to, the next.

When we see an apple, this identity is not something conceived at once like a concept; it is not an invariant found in all the various aspects; it is not a law or principle like triangularity found in all triangles. We see it by looking, by looking at the way this shiny red and dense white involves—makes visible—a certain sense of pulpiness, a certain juiciness, even a certain clear and homogeneous taste. What we see does not have that tomato look, that pear granularness, that peach feel. Each quality or aspect occupies its own spot and moment with its own schema, its own way of filling, condensing or rarefying its space and its moment. And there is an equivalence between a certain whiteness and a certain pulpiness; each reflects something of the schema of the other. The white is the white it is because it is condensed in this pulp, makes visible this contained liquidity, emanates this clear and tangy savor. The applesense is in that red and that white, in that pulpiness felt or chewed, in that taste and acrid smell. That “sense” is not an identity, an invariant, or a principle instantiated in different registers of sensoriality; it is a “style,” that is, the generality of a schema which is recognized by seeing that each phase is a variant of both the previous and the next one.4 The apple in the color, the pulp, and the savor is the style, like the personality is a style—a sensibly perceived schema that makes all the conversations of a person recognizably his or her own, even though one can isolate in them neither identical elements nor identical arrangements of elements that recur.

The sensible essence, the schema, the style, is given from the start; our perception does not first see the black color of the ball-point pen, but goes straight to the substance, the somber power condensing there, occupying a site, of which the black color, the dense matter, the hard solidity are registers that our analysis—first perceptual, then linguistic—then isolates. The thing itself is the materializing style.

The Transcendence of Things

This explication of the things that we perceive already makes it impossible for us to suppose that there is in them something given—”sense-data,” which are simples—and something we add to make things out of the data—the organization, the relations among them. For, on the one hand, without their cohesion, without their involvement in one another, the isolated sensible aspects can no longer be said to be anything. And, on the other hand, their cohesion or coherence is not a kind of unit, that of a meaning or a universal, which we grasp at once, intuitively; it is sketched out, open-ended, caught on to progressively, as we go further. Perhaps we see enough to attach a name to it from the start, but what a winesap apple or the calvados distilled from apples really is and means is something that we understand in touching, smelling, chewing, savoring, without ever ending at something like the definitive key to it—in the sense that, one day, having acquired the formula, we possess all there is to understand about a triangle.

The sensible elements themselves are not really particulars. They should not be defined as items that are what they are, when and where they are. Not one of them is just a here-and-now particular, contingent and unfounded such that it can only be recorded or not recorded.5 Each of them goes beyond simple location; there is not one that is instantaneous, that does not prolong itself in duration. And there is not one that is simply here: a point of red reduced to itself is not visible and is not red; it needs to be reinforced, prolonged by other spots, to be red. It is not simply red within its own borders since it can be the red it is only if the background is the color or colors it is. And this red looks tangible, is a tangible red.

Existential philosophy defined the new concepts of ecstasy or of transcendence to fix a distinct kind of being that is by casting itself out of its own given place and time, without dissipating, because at each moment it projects itself—or, more exactly, a variant of itself—into another place and time. Such a being is not ideality, defined as intuitable or reconstitutable anywhere and at any moment. Ex-istence, understood etymologically, is not so much a state or a stance as a movement, which is by conceiving a divergence from itself or a potentiality of itself and casting itself into that divergence with all that it is. This bizarre concept of an ecstatic or self-transcending existence was formulated so as to define the inner constitution of subjectivity and to distinguish it decisively from the way objective reality, the facts, are—which have to be located where and when they are because for them being is being at a point p and a time t. Now we find that it is this very concept of transcendence—on which the whole twentieth-century existential philosophy of subjectivity was built—that Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological existentialism calls upon in order to describe the irreducible givens, the sensory phenomena.

The increasingly elaborated conviction that the sensible givens have to be described, ontologically, as self-transcending existents commands the new descriptions of the sensible field we find in Merleau-Ponty’s later writings and in the posthumously published The Visible and the Invisible. The sensible field is a realm of being where all points become pivots, all lines become levels, all surfaces become planes, all colors become atmospheres, all tones become—as in dodecaphonic music—keys. There are not particulars and universals in the sensible field; what there are are particulars generalizing themselves, a whole landscape concretizing momentarily in this red, a whole love given in condensation in a vase of flowers, a whole adventure or fatality sounded in the five little notes heard in Swann’s Way. Each given is the spot and moment in which a schema of being is being elaborated. Artists have a precise knowledge of this; their knowledge consists in knowing what a color does to a field, to another color, to a zone of space; in knowing what a line does to the zone it molds, to the space it bunches up, bulges out, or flattens, to the color, to the field of tensions; and in knowing what shapes move, creep, crawl, leap, set up movement in a whole field.6 This knowledge is not conceptual; it is not a possession of laws or principles. Artists know how, with a few lines, a few strokes of color, to make things visible.

The Hold on Things

What, now, is the sensing of things? Classical epistemology, distinguishing in the thing perceived between the de facto multiplicity of sense-data and their relationships, whether additive or synthetic, distinguished also between a passive and an active side involved in the perceiving of things. There would be a passive receptivity for the sense-data, and an active collating or synthesizing of them. The sensing properly so-called would be a passive being-impressed by sensory qualia, psychic conversions of physiological stimuli. In Husserl’s phenomenology, intentionality intervenes to take these sense impressions to mean something, and thus to identify them, synthetically taking them as signs of one and the same signification. The intentionality makes impressions into sensations, that is, givens of sense, of meaning.

Merleau-Ponty takes the sensing to be active from the start; he conceives the receptivity for the sensuous element to be a prehension, a prise, a “hold.” The conception is Heideggerian; Merleau-Ponty envisions looking—palpating with the eyes7—tasting, smelling, and even hearing as variants of handling. The tactile datum is not given to a passive surface; the smooth and the rough, the sleek and the sticky, the hard and the vaporous are given to movements of the hand that applies itself to them with a certain pressure, pacing, periodicity, across a certain extension, and they are patterned ways in which movement is modulated. “The hard and the soft, the grainy and the sleek, moonlight and sunlight in memory give themselves not as sensorial contents but as a certain type of symbiosis, a certain way the outside has of invading us, a certain way we have to welcome it.”8 The striking experiments of Goldstein and Rosenthal9 enable us to extend this insight to visual data: the emergence of blue induces a sliding up-and-down movement across the body schema; the emergence of orange, an increased tension and extension of the body. Since a blue obtained by contrast is apprehended with the same sliding up-and-down movement, the movement cannot be understood as a motor reaction to a sensory impression defined by a certain wavelength and intensity; the sensitivity is motile from the start and it is in and by the modulation of the motility of the gaze, and of the whole body that steers and supports the eye movements, that the blue or the yellow is sensed, that is, taken up, communicated with.

The moist, the oily, the sleek, the restful green, and the aggressive orange are palpated by the hand or the look, which takes up in its own positioning and pace something which in it is an induced program for its own motility, and which, in the thing, is the sensible essence, the essence of oiliness or of green. This essence has to be conceived verbally (like “insistence,” “dissidence”); it is a specific way of occupying its space and time actively, of condensing or rarefying its space and moment, of bulging it out or hollowing it out, a specific way of polarizing, sustaining, spreading its tension across a certain field. The inner sense of the green is also realized in its own way in the register of the tangible, in the pulp of the cucumber, and in the register of flavor and odor. Already the whole palpable and edible cucumber is captured by the movement of the eyes.

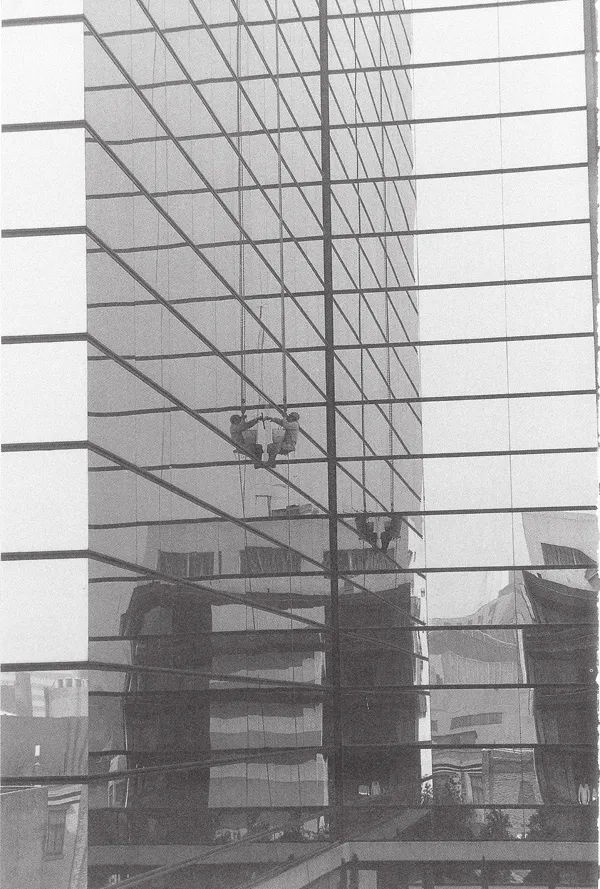

A gesture captures the sense of something. The hand that rises to respond to a gesture hailing us in the crowd is not preceded and made possible by a representation first formed of the identity of the one recognized. It is the hand that recognizes the friend who is there, not as a named form represented, but as a movement and a cordiality that solicits—soliciting not a cognitive and representational operation from us, but a greeting, an interaction. The hand itself in the range of its gesture signals our presence and our welcome, measures the distance between us, and effects the recognition. How do we recognize the brash and garish colors of the Snopes suburbs, the bluegreen waters of the coral seas, the lines of the giant sequoias rising on the landscape? They too are recognized in the movements with which we face them.

The sizes and shapes of things are also captured actively; it is in dilating the scope of my look or my grip, eventually filling out the whole field—that is, approaching the limit of what my look or my hearing can hold together before me—that the bigness of the visual object or the full-bodiedness of a sound comes to be and becomes manifest. In the equilibrium of my gaze traveling about the rim of the plate the circular is sensed and comes to be before me. In experiencing the length of the wall becoming less clearly articulated for me I feel that end of it pulling away from the hold I have on it, and thus oriented away from me, receding into distance. It is my maximal hold on it—when its form and grain are clear and distinct for me, when I feel myself centered on it—that determines the normal, true, or right appearance of a thing from its variants, from shapes turned to the side, from round or rectangular planes set askew, from things of comparable size staggered out over a distance, from white sheets of paper scattered in the dim light of the hall.

Things have their own orientation. Things are recognized to be right-side-up, front-side-facing when we sense ourselves positioned before them in ways that can explore and handle them efficaciously. The sense, the recognizability, of a thing is in its right-side-up, front-side-facing orientation (in French “sens” means both “meaning” and “direction...