eBook - ePub

Engaging the Public with Climate Change

Behaviour Change and Communication

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Engaging the Public with Climate Change

Behaviour Change and Communication

About this book

Despite increasing public awareness of climate change, our behaviours relating to consumption and energy use remain largely unchanged. This book answers the urgent call for effective engagement methods to foster sustainable lifestyles, community action, and social change. Written by practitioners and academics, the chapters combine theoretical perspectives with case studies and practical guidance, examining what works and what doesn't, and providing transferable lessons for future engagement approaches. Showcasing innovative thought and approaches from around the world, this book is essential reading for anyone working to foster real and lasting behavioural and social change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Engaging the Public with Climate Change by Lorraine Whitmarsh,Irene Lorenzoni,Saffron O'Neill, Lorraine Whitmarsh,Saffron O'Neill,Irene Lorenzoni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

THEORIES AND MODELS

How can different theoretical perspectives help us develop effective communication and behaviour change strategies and understand the limits to public engagement?

1

Old Habits and New Routes to Sustainable Behaviour

1. Introduction

Although people are sensitive to what they think are beneficial or detrimental choices, most behaviours seem to be driven by mere repetition and habit rather than by conscious deliberation of costs and benefits. This also holds for behaviours that have a potential impact on our natural environment. In this chapter, I first discuss models of environmental behaviour. I then focus on the repetitive nature of behaviour. I will outline why old, unsustainable habits form barriers to change, but I will stress also that there exist opportunities to turn new, sustainable behaviours into habits. Finally, I argue that as climate change requires drastic changes in behaviour amongst large sections of our societies, time is running out to wait for people to change their values and attitudes, and measures are necessary that directly regulate behaviour. Psychologists may have much to offer in making this happen in socially acceptable ways.

2. Antecedents of environmental behaviour

Models of expected utility and planned behaviour

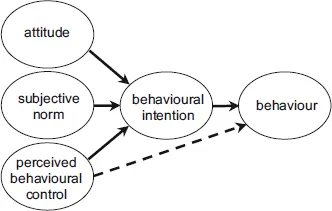

Why do we behave as we do? Common sense perhaps tells us that our behaviour is guided by the balance of perceived costs and benefits; that is, overall value. When we shop, we choose products that we think provide value for money. When we travel, we consider attributes such as travel time, monetary costs and comfort. In our homes we use the appliances and gadgets that we consider useful or pleasurable. The assumption underlying this view is that people are driven by maximizing the expected value of a particular behaviour. This indeed is the prevalent view of behaviour amongst economists, and forms the basis for influential models of behaviour in psychology. Whereas economists interpret ‘value’ in monetary terms, psychologists use the concept of ‘utility’, or more precisely ‘subjective expected utility’, to designate the expectation of the perceived value of a behavioural outcome (Edwards, 1954). The principle of subjective expected utility became the key building stone of prevalent models of behaviour, most notably the theory of reasoned action (TRA; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980) and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, 1988). According to these models, the specific perceptions of expected costs and benefits associated with a behavioural choice (e.g. price, comfort, usefulness) lead to the formation of an attitude. An attitude is a summary evaluation; that is, how favourable or unfavourable one feels towards engaging in that behaviour. TRA and TPB suggest that attitudes guide behaviour through the operation of behavioural intentions. An intention thus represents a person's motivation to engage in a particular behaviour. The models propose that in addition to an attitude, intentions are also determined by the felt pressure from the social environment, such as expectations of friends or family, which is represented as a subjective norm. In addition, the TPB, which is an extension of TRA, includes the perceptions of control over behaviour (e.g. perceived difficulties) as a third determinant of intentions. Perceived behavioural control is assumed to determine intentions or, if the perception of control reflects actual control, behaviour directly. The TPB is represented in Figure 1.1.

Research over almost four decades has provided a strong evidence base for the validity and utility of the TRA and TPB in a wide variety of behavioural domains, including ecology-related behaviours. A series of meta analyses demonstrated that intentions are reasonably good predictors of behaviour (Armitage and Conner, 2001; Ajzen and Fishbein, 2005), and typically explain some 25 per cent of the variation in behaviour (Sheeran, 2002). Also, the prediction of intentions by attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control has received firm empirical support (e.g. Armitage and Conner, 2001).

Source: Ajzen, 1999

Figure 1.1 The theory of planned behaviour

Some important caveats should be noted. The first is that the arrows in the TPB model suggest causal relations. Behaviour is thus assumed to be caused by an intention, while intentions are considered to be caused by some combined influence of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. There is some but not a great quantity of empirical evidence to support this claim, while there are demonstrations of reverse causal flows as well, such as self-perception processes whereby individuals ‘infer’ their attitudes from their behaviour (Olsen and Stone, 2005; see later). Secondly, the model suggests that all influences on behaviour, whether these are internal (e.g. personality) or external (e.g. external information), are routed from left to right in the model. In other words, these factors are assumed to influence attitude, subjective norm or perceived behavioural control, and thus intentions and behaviour. In one sense, this is a strong aspect of the model; it maps alternative routes to behavioural change. For instance, information campaigns may be tailored to the leg of the model that drives a particular behaviour. Information may thus be provided that either changes the balance of perceived costs and benefits (the attitude route), beliefs about norms (the normative route) or ways to overcome particular barriers to behaviour (the perceived control route). On the other hand, there is some evidence that behaviour may be influenced by factors that are not mediated by the model variables, such as impulsive or non-conscious processes. I will return to this issue when discussing the role of past behaviour and habit.

The TPB model reveals potential problems for attempts to change behaviour through the provision of information: even if information changes attitudes, subjective norms or perceptions of behavioural control, this does not guarantee changes in intentions and certainly not changes in behaviour. The links between attitudes and intentions and behaviour are particularly fragile when attitudes are weak in the first place; for instance, when individuals are uninvolved in, or ambivalent about, a particular issue (Petty and Krosnick, 1995). Also, if information affects one of the antecedents of intention (e.g. an attitude), there may remain a reverse influence of other antecedents (subjective norm or perceived behavioural control), which thus may maintain the original intention and behaviour. Finally, although intentions predict behaviours reasonably well, there remains a gap. Intentions may not be enacted for a host of reasons. For instance, intentions may not be well formed or may be temporally unstable (e.g. Sheeran et al, 1999; Ajzen, 2002). There may also be problems in the execution phase, such as not knowing how or when to start, getting derailed, or simply forgetting one's intentions (e.g. Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006).

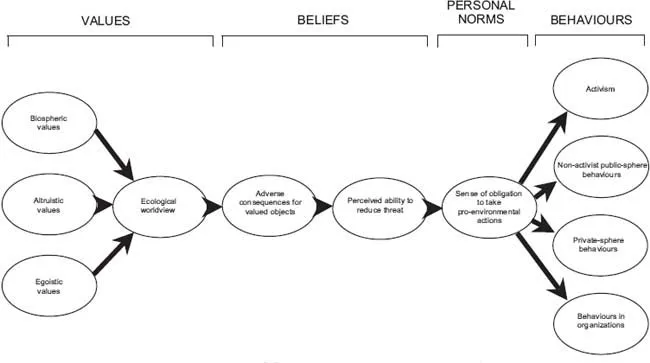

Other models of pro-environmental behaviour

Although the TRA and TPB as general models of behaviour have been successfully applied to document and predict pro-environmental behaviours, other models have been developed specifically for this behavioural domain. Some are extensions of the TRA/TPB, such as the addition of personal norms (Harland et al, 1999) or self-identity (e.g. Terry et al, 1999). Other models have their roots in the norm-activation theory of altruistic behaviour (e.g. Schwartz, 1977). This theory asserts that altruistic behaviour is driven by ‘personal norms’ (i.e. a sense of personal obligation), which are associated with fundamental values. This theory proposes a causal chain of variables that leads to pro-environmental behaviour. The chain starts with relatively stable altruistic personal values and beliefs about the relation between humans and the environment. These beliefs are activated when individuals are confronted with environmental conditions that violate them. This in turn activates beliefs that valued objects are threatened, beliefs about the individual's ability to act and the felt responsibility to act, which may then lead to a choice of pro-environmental action. A suite of models based on the norm-activation theory have recently been integrated into the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory of environmentalism (Stern, 2000). This model is depicted in Figure 1.2.

The VBN theory stipulates the importance of altruistic personal values and an ecologically friendly worldview for pro-environmental behaviour. The model thus suggests ways to promote pro-environmental behaviours among segments of the population who hold pro-environmental norms and values, but do not translate these into action. The model also points towards the difficulty of changing ecologically unfriendly behaviour; the most problematic segments of the population may not endorse the pro-environmental norms and values in the first place, which the VBN theory specifies as being conditional to change. In general, values do not easily translate into behaviour. In an experimental programme, Verplanken and Holland (2002) demonstrated that values are enacted only if they are central to a person's self-concept and are cognitively activated. Two important observations were thus made. The first is that cherishing pro-environmental values per se does not necessarily lead to pro-environmental action, even when the opportunity to act in an environmentally friendly way arises. The second observation is that drawing people's attention to pro-environmental issues leads to action only if pro-environmental values are part of a person's self-identity (i.e. their sense of who they are). This may indeed be quite rare. The VBN model therefore seems to apply only to individuals who prioritize pro-environmental values and to actions that are clearly earmarked as serving pro-environmental goals. For some, pro-environmental values may drive energy conservation behaviour (e.g. Black et al, 1985), but often low-carbon choices are motivated by non-environmental considerations such as saving money, convenience or health benefits (Brandon and Lewis, 1999; Whitmarsh, 2009). One study (Bamberg and Schmidt, 2003) sought to compare the efficacy of different behavioural models, including the TPB and a norm-based model (a predecessor of the VBN), in predicting students’ transport choices, and found that energy use is primarily determined by perceived personal costs and benefits and by habit (see next section), while moral concerns are less influential. Even people with high pro-environmental values will tend to conserve energy only if the threat to self-interest (e.g. cost) is not considered too great (Black et al, 1985; Clark et al, 2003; Poortinga et al, 2004). In sum, it is clear that energy use and energy conservation actions are typically a product of a complex ecology of motivations and external influences, and that consequently there is little consistency in apparently ‘low-carbon’ behaviours across different contexts such as home, work, travel and leisure (e.g. Darnton, 2008).

3. The role of past behaviour and habit

Although the models discussed so far have proven useful (at least in certain contexts), they do not do justice to the dynamic nature of behaviour. In particular, they do not incorporate the notion that most behaviours are repeated over and over again. The role of previous behaviour has always been elusive and problematic in models of behaviour. In spite of the assumption contained in the TRA and TPB models that previous experiences feed into future behaviour through their impact on the model variables (e.g. attitudes), a robust finding is that past behaviour retains predictive power of future behaviour over and above all model variables. There are a number of explanations why this phenomenon is observed (e.g. Ajzen, 2002). For instance, past behaviour may be a better guide for future behaviour when attitudes and intentions are ambivalent or not well formed. It may also be that expectations one has about behaviour are inaccurate, which renders intentions inadequate in the face of reality. However, another possibility is that previous behaviour has turned into a habit, which may attenuate the influence of attitudes and intentions.

Source: Stern, 2000

Figure 1.2 The value–belief–norm (VBN) theory of environmentalism

Habits are repeated behaviours that have become automatic responses in recurrent and stable contexts (e.g. Verplanken and Aarts, 1999; Wood et al, 2002; Verplanken and Orbell, 2003; Verplanken, 2006; Wood and Neal, 2007). Habits have three key features. The first is repetition; habits form by successfully repeating behaviour. ‘Successfully’ should be interpreted in a wide sense. It may not be confined to what objective observers would see as desirable. A habit may be successful from a personal perspective; for instance, because it is comfortable or provides status, but unhealthy, asocial or environmentally unfriendly from an outsider's perspective. Importantly, although a habit implies repeated behaviour, repeated behaviour is not necessarily habitual. For instance, decisions that have pervasive consequences, such as diagnosing patients or operating nuclear power plants, hopefully do not turn into habits. The second key feature of habit is automaticity (e.g. Verplanken and Aarts, 1999). ‘Automaticity’ itself can be broken down into features such as the absence of conscious intent, lack of awareness, the difficulty to control, and the fact that habitual behaviour does not tax cognitive resources (Bargh, 1994). The third key feature of habit is the fact that habits are executed in stable contexts (e.g. Wood et al, 2002). We do our habits often more or less at the same location and at the same time. An important caveat is that habitual behaviours are to a large extent under control of the environment where the acts take place. That is, one executes a habit not because of a conscious intention or willpower, but because it is 8 a.m. or because one passes by a particular shop. Those cues thus seem to regulate our behaviour, rather than our attitudes or intentions.

The mechanism that drives habits implies that habits do not follow the processes implied by the models discussed earlier. As a matter of fact, there is quite some evidence that frequent and habitual behaviour is less well described by models such as the TPB. For instance, Ouellette and Wood (1998) found, in a meta-analysis of studies that included measures of intention, past and later behaviour, that behaviour correlated less strongly with intentions when it was frequently performed. Primary studies also demonstrated that intentions were less or not at all predictive of behaviour when strong habits had been formed. For instance, Verplanken et al (1998) found near-zero correlations between intentions to travel by car versus public transport and actual travel mode choices among participants with strong car use habits, whereas intentions of those with weak habits predicted behaviour very well. Other evidence for the absence of deliberation and intention when habits have formed comes from research on information processing (Aarts et al, 1997; Verplanken et al, 1997). Us...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- List of Contributors

- Foreword by Susanne Moser

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction Opportunities for and Barriers to Engaging Individuals with Climate Change

- 1 Theories and Models How can different theoretical perspectives help us develop effective communication and behaviour change strategies and understand the limits to public engagement?

- 2 Methods, Media and Tools How can we more effectively communicate with the public about climate change and energy demand reduction?

- Index