Chapter One

THE DIMENSIONAL ANALYSIS OF ANXIETY AND HYSTERIA

THE function of science may be stated very broadly to be twofold. It attempts to describe phenomena, and it attempts to explain them. This is not in any sense an absolute distinction; explanation is no more than a very extensive method of description. The law of gravitation explains the falling of unsupported bodies, the movements of the planets, the swing of the pendulum, and many other phenomena, but at the same time it is itself merely a general descriptive formula derived from the facts it then explains. There is thus a certain circularity in all scientific reasoning, but this circularity is not objected to as long as its basis is broad enough. In other words, if we are only dealing with one or two facts, ‘explanation’ derived from description is tautological. When the facts are very numerous the tautological aspect of explanation vanishes and it becomes generally predictive and scientifically important.

In the field of abnormal behaviour, we can distinguish the same two aspects in the endeavours of psychologists and psychiatrists to deal with the observed phenomena. Classical psychiatry was largely concerned with the description of symptoms and the establishment of syndromes; it seldom ventured far beyond the descriptive realm. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, attempted to explain the causes of syndromes and symptoms, and for that reason seemed to consider itself justified in calling its approach ‘dynamic’.

The general outcome of all this work cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be called impressive. On the descriptive side, even a cursory glance at modern textbooks will show a remarkable lack of agreement between different groups of psychiatrists. Indeed, even within any one group it will usually be found that there are grave inconsistencies in the views put forward. Thus, the same author may on one page treat syndromes as separate disease entities, while on another page he may put forward a view implying rather the existence of quantitative continua. It is small wonder that psychiatric diagnoses show very little reliability (Eysenck, 1952), or that many psychiatrists have come to despair of this type of description as being at all useful in their day-to-day work.

Nor has the ‘dynamic’ approach fared any better. Here also disagreement on even the most elementary and fundamental facts is such that it is very doubtful whether any agreed and settled theory may be said to exist at all (Blum, 1953). Here also inconsistencies arise within the writings of any particular author or school. Worst of all, the initial promise of psychoanalysis to improve or cure the mentally ill has not been fulfilled after over 50 years of widespread endeavour. A review of all the available evidence by the present writer disclosed the sad fact that when comparing the effects of psychotherapy with various estimates of spontaneous remission rates, there appeared to be no difference between cures accomplished (Eysenck, 1952).

What, it may be asked, has gone wrong? Why has the achievement both of classical and of dynamic psychiatry so clearly belied its early promise? The answer, or so it seems to the present writer, must lie in the method adopted by psychiatrists. By and large they tend to appeal to intuition, clinical insight, and experience in formulating their views, and to reject experimental methods and statistical analyses. This does not seem to be a feasible position. No one would deny the importance of clinical experience and insight in the formulation of hypotheses and theories; indeed it is difficult to see any other breeding-ground for these vitally necessary parts of scientific progress. It is a grave error, however, to assume that the formulation of a hypothesis constitutes an acceptable proof for that hypothesis. It is to achieve such a proof that experimental and statistical analyses are essential. The clinical method, so called, is an excellent method for suggesting ideas, but its usefulness ends at that point. It is a grave defect of post-Kraepelinian psychiatry that it has rested content with theories and has eschewed the hard and difficult task of proof. This is all the more astonishing as Kraepelin himself had instituted the use of psychological experiments in psychiatry and demonstrated their fruitfulness. Yet, what he said over 50 years ago still very much applies today:

‘However much our creative confidence may be diminished by difficulties and disappointments, and however many of our great problems may prove to be insoluble in their present form —nevertheless, our experience has already shown beyond doubt that the psychological experiment is not only a useful but an indispensable part of our scientific background. It is all the more important because in psychiatry, more than in any other branch of medicine, interpretation and system building are regarded more highly than simple observation. In our psychiatric case conferences we constantly find a superabundance of individualistic brilliance, an undisciplined arbitrariness which finds sufficient room for its games only because as yet the slow advance of real science has not narrowed down the possibilities sufficiently. Nearly every psychiatrist assumes the right —some even seem to regard it as an obligation!—to begin by constructing his own psychological system on the basis of rough-and-ready observations of patients, of animals, or even by reference to literary studies. What representative of internal medicine would dare to proclaim a new system of physiology which did not base itself on facts laboriously acquired and tested in the laboratory?’

In many ways the work which the writer has reported in this and previous volumes is nothing more than a continuation of the work so well begun by Kraepelin and his students. Previous volumes, in particular Dimensions of Personality and The Scientific Study of Personality, have dealt with the descriptive aspects of abnormal behaviour; the present book constitutes an attempt to deal with some of the aetiological, or causal, problems thrown up in these earlier books. The present chapter is devoted to a brief review of the present position in the descriptive, nosological, or taxonomic field; the remainder of the book will then proceed from this foundation to a discussion of explanatory concepts and their application to certain parts of the descriptive scheme. As this chapter is largely a review of previous work, no effort will be made to prove in detail the various points made; for such proofs the reader is referred to previous publications. We shall rather present the results achieved together with certain illustrative material, and briefly mention the statistical and experimental methods used.

The first issue to be raised is that of continuity. It used to be argued by analogy with physical diseases, that the syndromes of psychiatry, such as hysteria, constitute separate disease entities possessing separate diagnostic, prognostic, and aetiological features. While this view is not very widely held today, the nomenclature and the systems of diagnosis employed by psychiatrists still make use of it, and it is rare to find an outright refutation of this notion. Nevertheless, this view is quite untenable, both on clinical and experimental grounds. Functional psychiatric disorders are not ‘diseases’ at all, in the sense that malaria or cancer or haemophilia may be said to be diseases which a person may be said to have or not to have. There are no qualitative differences between so-called normal people and those diagnosed as suffering from anxiety state or hysteria. The difference is a quantitative one, just as is the difference between the average person and the dullard with an I.Q. of 70 is quantitative. The medical notion of mental disease entities is not, in fact, entertained seriously by most psychiatrists, and it is proposed, therefore, that it should formally be relinquished.

In its place we must put an entirely different notion, namely that of a number of separate dimensions or continua, the interaction between which gives rise to the so-called syndromes of classical psychiatry. What these continua are and how they can be established is an important problem which will be illustrated by references to a second problem, namely, that of the identity —or lack of identity—of the neurotic and psychotic continua.

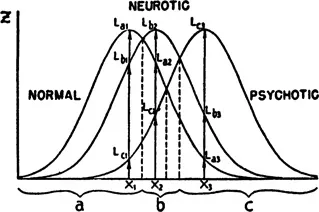

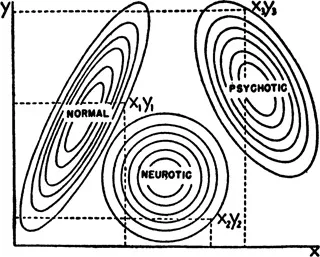

As is well known, classical psychiatry regards neurotic and psychotic disorders as being essentially different, i.e. as lying on two independent, orthogonal continua. Psychoanalysts, and some other modern psychiatrists, on the other hand, believe, as Myerson (1936) puts it, that ‘neuroses span the bridge between . . . normal mental states and certain psychotic states’. In other words, they believe that there is a single continuum from normal through neurotic to psychotic, so that a person suffering from neurotic disorders might be considered as a mild psychotic, or a person suffering from psychotic disorders as a severe neurotic. The two hypotheses may be illustrated as in Figs. 1 and 2.

This problem is of obvious and fundamental importance to psychiatry, and its treatment in the literature brings out particularly clearly the failure of the so-called clinical method to supply any kind of proof one way or another. A perusal of several hundred books and papers dealing with this question discloses that the opposing arguments can, in fact, be reduced to the following: ‘My clinical experience suggests that there is a continuum between neurotics and psychotics’, and, ‘My clinical experience suggests that there is no continuum between neurotics and psychotics’. Admittedly, other arguments are occasionally brought forward, such as the fact that patients can be found who seem to have both neurotic and psychotic symptoms, and who are difficult to diagnose as either one or the other. Such observations, while factually correct, do not provide an argument either way, however. On the one-dimensional hypothesis such people would be postulated to lie between points X2 and X3 in Fig. 1. On a two-dimensional hypothesis, they would be postulated to lie between points X2 and Y2, and X3 and Y3 in Fig. 2. Thus, both fact and argument are irrelevant to the discussion. Clearly, then, the clinical method has failed to provide any plausible solution to our problem. Where clinical experience contradicts clinical experience, clinical experience cannot be the criterion. If we wish to escape from an eternal impasse of this kind, we must adopt a more systematic experimental-statistical approach.

FIG. 1. One-dimensional hypothesis of personality organization.

FIG. 2. Two-dimensional hypothesis of personality organization.

One possibility of doing this is by means of a statistical study of the relationships between symptoms actually observed in a representative group of psychiatric patients. Such a study is available in the work of Trouton and Maxwell (1956), who made use of a set of 45 symptoms whose presence or absence was rated by the Psychiatrist-in-Charge on 819 male functional patients at the Maudsley Hospital, aged between 16 and 59 years. The variables included are shown in Table I. Tetrachoric correlations were ca...