![]()

Our understanding of bilingualism would be greatly improved if data were systematically collected about the course of aphasia in bilingual patients.

—Lambert and Fillenbaum (1959 p. 29)

The basic questions in the neuropsychology of bilingualism are whether the two languages of the same subject have different cerebral representations and whether the fact of having acquired two languages influences the cerebral organization of higher cortical functions. Several hypotheses have been proposed, each based on some isolated observational data and much speculation. Most theoretical claims still await empirical verification.

First, there is the long standing neurological claim that all languages of a polyglot are subserved by the same cortical locus or loci. A more recent theoretical linguistic position assumes that all languages share the same linguistic principles and that, therefore, the underlying cerebral representation must be the same for all the languages of a speaker-hearer. It predicts that if some aspect of competence is impaired by neurological trauma, then all languages known by the speaker must be disordered in just the same way, consistent with the impaired competence. Thus, according to this hypothesis, there is no specific cerebral representation for each language (as langue) but only a single undifferentiated capacity for language in general (langage). Consequently all languages are subserved by a common cortical area or jointly distributed over the classical language areas (e.g., Broca's, Wernicke's).

Questions specific to bilingual aphasia are added to those stemming from aphasia in general, such as whether aphasia is a general cognitive deficit or a language-specific impairment; whether it is a unitary phenomenon or admits of multiple syndromes; whether it is a deficit of competence or performance; and whether modality-specific deficits are aphasic symptoms. Theoretical positions on these issues will have consequences for hypotheses about bilingual aphasia and/or the representation of two languages in one brain.

Some authors, for example, argue that patients are not aphasic unless their competence is impaired. Competence is considered not to be impaired when a deficit is not equally manifested in all modalities or when a patient undergoes spontaneous recovery. Moreover, because it is assumed that competence is common to both languages, if a bilingual is agrammatic for some aspect of the grammar in one of his languages, it is predicted that she or he will be agrammatic for those same components of the grammar in the other language (Scholes, 1984). Thus, what recovers spontaneously in unilinguals and bilinguals as well as what is differentially deficient in bilinguals is not considered a result of impaired competence but of loss of access through some defective performance mechanism. Such a position therefore holds that any bilingual patient exhibiting nonparallel recovery is not aphasic.

Whether or not we call patients aphasie who have lost the use of one of their languages or who have differential postmorbid proficiency in each language, it is of interest to the neuropsychology of language in general and of bilingualism in particular to examine whether nonparallel deficits do indeed occur, and if so, to investigate the mechanisms responsible for differential, successive, selective, antagonistic, and mixed recoveries. In fact, there is no a priori reason to reject the possibility that each language might be subserved by its own competence, namely, that each grammar might be separately stored and/or processed. There is indeed no clinical evidence that there is only one underlying neurolinguistic competence for both languages, that is to say, one common neural substrate for language, undifferentiated as to specific language. If it can be shown that specific alterations in competence occur in one language and not in the other, then it is not unreasonable to assume that each language is subserved by different neuro-functional substrates. Further systematic investigations, based on large numbers of successive unselected cases and using identical testing procedures, should help us solve the puzzle of differential recoveries and eventually provide us with clues as to whether the various languages of a polyglot are stored and processed by the brain separately, each as an independent linguistic system, or together, as one single linguistic competence.

While authors from Pitres (1895) to Penfield (1953, 1959, 1965) through Pötzl (1925), Minkowski (1927, 1963), Veyrac (1931), Ombredane (1951), and Gloning and Gloning (1965) have argued against separate centers specifically assigned to each of the languages of polyglot subjects, a growing number of contemporary researchers are prepared to consider various kinds of differential representation, including distinct anatomical localization. In fact, some have come to believe that “it would be surprising if bilingualism had no effect on brain organization” (Segalowitz, 1983, p. 121). According to these authors, there are numerous reasons to believe that cerebral representation of language is not entirely the same in polyglots as in unilinguals (Lecours, Branchereau, & Joanette, 1984, p. 20). The two languages of a bilingual may not be subserved by exactly the same neuronal circuits; it may even be that they are differently lateralized (Lebrun, 1981, p. 68).

Bilinguals have two languages at their command. They can speak one or the other and understand either at any time. They can switch between them, and they can mix them at any level of linguistic structure (phonetic, phonological, morphological, syntactic, lexical, semantic). Bilingual aphasics have been reported to lose some of their linguistic abilities selectively, as well as the ability to translate in either direction or in both (Paradis, Goldblum, & Abidi, 1982). Segalowitz (1983, p. 156) considers the fact that two languages in a bilingual patient can be differentially affected by brain damage as a strong argument for some separate representation in the brain. But, as he rightly notes, the nature of their separation is still unexplained. It has given rise to a number of suppositions.

According to one of these, the various languages of the polyglot are represented in different anatomical loci within the same general language zones (the classical language areas). Though, as mentioned earlier, it has had many detractors, some of them quite vehement, this hypothesis has never had any serious proponents. Scoresby-Jackson (1867) is generally credited with having come closest to such a suggestion. Another view is that the two languages of a bilingual are represented in partly different anatomical areas in the dominant hemisphere, with some overlap (Ojemann & Whitaker, 1978; Rapport, Tan, & Whitaker, 1983).

But assuredly the most debated issue has been the successive reformulations of the basic differential lateralization hypothesis which assumes a greater participation of the nondominant hemisphere in the representation and/or processing of language in bilinguals.

First of all, the nature of the alleged participation of the right hemisphere is far from clear. The classical view is that the right hemisphere of right-handers has no linguistic capacity. It may acquire some, but only when the left hemisphere is damaged early in life, and then only to some extent. Another assumption is that the language capacity of the right hemisphere is virtually the same as that of the left, but is inhibited by the functional left hemisphere and released only when the left hemisphere is incapacitated. But assuming that the right hemisphere does participate in the processing of language, then it is legitimate to ask what the nature of this participation which supposedly increases with bilingualism could be. At least four possibilities come to mind.

Let us call the first the redundant participation hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, both hemispheres process information in identical ways, though the participation of the left hemisphere may be quantitatively greater. The processing by the right hemisphere is redundant and hence the removal of the right hemisphere is of little consequence for language.

Another possibility would be the quantitatively complementary participation hypothesis according to which, as above, each hemisphere processes the same stimuli in the same way, with greater participation of the left hemisphere. However, there is a mass effect and the whole is necessary for normal language processing. A lesion to homologous parts of either the right or the left hemisphere will cause qualitatively identical deficits proportional to the extent of the damage.

One can also conceive of a qualitatively parallel participation hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the same stimulus is processed in a qualitatively different way by each hemisphere. Each hemisphere processes all aspects of a stimulus in accordance with its own inherent mode of functioning. The participation of the right hemisphere is thus qualitatively complementary to that of the left hemisphere in processing utterances.

Still another plausible candidate is the qualitatively selective participation hypothesis. Each hemisphere, in accordance with its intrinsic functional capacities, specializes in the processing of a different aspect of a complex stimulus. In this case, as in the previous one, the participation of the right hemisphere is qualitatively complementary to that of the left hemisphere. However, while in the qualitatively parallel participation hypothesis complementarity is with respect to each aspect of an utterance, in the qualitatively selective participation hypothesis it is with respect to the utterance as a whole.

The qualitatively parallel participation hypothesis predicts that a lesion in the right hemisphere will affect all aspects of the utterance (albeit in a specific way, distinguishable from the effects of a homologous left-hemisphere lesion; e.g., global vs. analytic-sequential decoding of the meaning of a word or phrase), whereas the qualitatively selective participation hypothesis predicts that a right-hemisphere lesion will affect certain aspects of the utterance (a homologous left-hemisphere lesion will affect the other aspects of the utterance; e.g., prosody related to emotional states vs. grammatical stress pattern or lexical tone).

The redundant and the quantitatively complementary participation hypotheses assume an identical processing of the same aspects of an utterance; the qualitatively parallel participation hypothesis assumes a different processing of the same aspects; while the qualitatively selective participation hypothesis assumes a different processing of different aspects. Among the most often mentioned intrinsic processing modes attributed to each hemisphere, one finds the analytic/global, sequential/concomitant, logical/analogical, context-independent/context dependent, and deductive/inductive. Aspects of an utterance that have been invoked as likely to be processed separately by each hemisphere are, among others, grammatical/paralinguistic, phonemic/prosodic, and syntactic/pragmatic.

The situation gets even more complex in the case of language cerebral lateralization in bilinguals. In the first place, researchers do not even agree on the facts. Then, they further disagree on the interpretation of these controversial facts. That is, while some authors decide in favor of an increased participation of the right hemisphere in the processing of a second language (Gloning & Gloning, 1965; Minkowski, 1963; Ovcharova, Raichev, & Geleva, 1968; Vildomec, 1963), others conclude that bilingualism actually intensifies the development of cerebral dominance for language (Stark, Genesee, Lambert, & Seitz, 1977). Still others see no difference between unilinguals and bilinguals with respect to lateralization of language (Gordon, 1980; Piazza Gordon, & Zatorre, 1981; Soares & Grosjean, 1981; Walters & Zatorre 1978). In fact, several hypotheses have been proposed concerning the extent of right hemisphere participation in the processing of language in bilinguals, as follows: The second language is represented (or processed) in the right hemisphere; the second language is represented bilaterally; the second language, while mostly lateralized to the left, is less so than the first; both languages are less lateralized; both languages are equally represented in the left hemisphere; both languages are more lateralized (Obler, Zatorre, Galloway, & Vaid, 1982; and Galloway, 1983; for a critique of the experimental literature, see Zatorre, 1983; for details, see Vaid & Genesee, 1980).

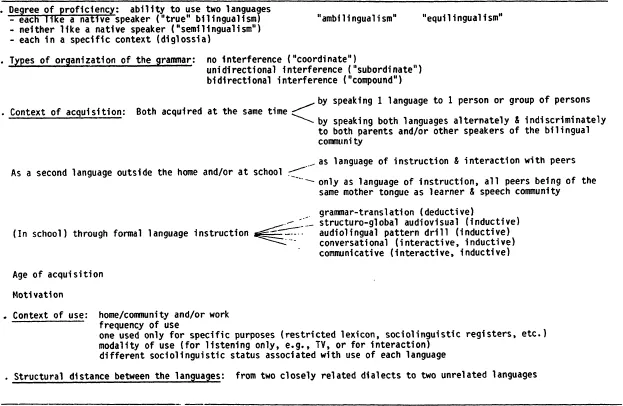

An additional question is whether the manner of representation (i.e., one of the above possibilities) is the same in all bilinguals, irrespective of the kind of bilingualism, or whether it is a function of one or several of the acquisitional, utilizational, or structural dimensions of bilingualism (see Table 1.1). In fact, among 15 bilinguals observed by Hamers & Lambert (1977), 3 subjects appeared to have right hemisphere dominance for both languages, 2 subjects seemed to possess one language in the left hemisphere and the other in the right, while 3 more showed a substantial left processing of one language and no left-right difference in the other. Yet, in spite of the lack of clear evidence in favor of one or the other of the above hypotheses, a number of further hypotheses have been formulated to account for the alleged greater participation of the right hemisphere found by some in the processing of language in bilinguals. Some authors have even gone so far as to suggest that the right hemisphere is specialized for the acquisition of a second language (Ovcharova et al., 1968; Vildomec, 1963). But as clinical observations and/or experimental results have invalidated this initial hypothesis, a series of tentative explanations have been formulated. In effect, each new attempt has further restricted the bilingual population to which the greater participation of the right hemisphere hypothesis was supposed to apply: The age hypothesis, according to which a language learned after puberty is less lateralized because of the difference in maturational states during acquisition; the stage hypothesis, according to which the second language is gradually lateralized to the left hemisphere as that language is better mastered; the revised stage hypothesis, according to which the increased participation of the right hemi sphere is limited to adults at the beginning of the acquisition of a language in a natural environment, but not through formal learning; the type of bilingualism hypothesis, according to which coordinate bilinguals (in whom the languages are supposed to be more separate) have their languages represented separately, with a greater participation of the right hemisphere than for compound bilinguals; the context hypothesis, according to which right hemisphere participation is greater in a second language context than in a foreign language context; the modality hypothesis, according to which the learning of a second language through reading and writing promotes greater left hemisphere participation while acquisition by ear promotes greater right hemisphere participation; the language-specific hypothesis, according to which some characteristics of a given language may foster right hemisphere participation, these characteristics ranging from differences in the organization of thought patterns, to vowel characteristics, to tone, to directionality of writing; and the structural distance hypothesis, according to which two languages that are structurally very different (e.g., English and Japanese) are represented more separately, with greater participation of the right hemisphere than with two closely related languages (e.g., Catalan and Spanish).

TABLE 1.1

Variables Associated With Differences Among Bilinguals

It is not the case, as has often been claimed, that studies of dominance in aphasics have demonstrated that more aphasia is found following right hemisphere lesions in bilinguals (10 per cent) than has been reported for unilinguals (2 per cent) (Hughes, 1981, p. 27). Such statistics are very misleading at best, and are probably false. The reason is very simple (and has often been quoted, including by those authors who then nevertheless go on to use those figures in support of their argument): Since most cases of aphasia subsequent to left hemisphere damage are not reported, and since most cases of crossed aphasia—unilingual or bilingual—do get reported because of their exceptional character, one cannot conclude from the few selected cases of aphasia in bilinguals reported (contrasted with the large populations of unselected consecutive cases of unilingual aphasics from whom incidence of crossed aphasia has been derived), that the right hemisphere plays a greater role (let alone “a major role”) in bilinguals (yet, see Albert & Obler, 1978; Galloway, 1980; Hughes, 1981; Lebrun, 1981). In addition, the study by Nair & Virmani (1973), which represents the main source of clinical evidence adduced to bolster the hypothesis that bilinguals are less strongly lateralized for language than unilinguals, has been radically and repeatedly misinterpreted: No comparison between the incidence of crossed aphasia among bilingual and unilingual subjects can possibly be derived from their report (Solin, forthcoming).

It may be useful, at this point, to make a clear distinction between language representation (i.e., linguistic competence) and language use (i.e., performance). Clinical evidence overwhelmingly points in the direction of quasi-exclusive representation of language in the left hemisphere in at least 95% of righthanders (but see Lecours, 1980), while the right hemisphere undoubtedly participates in the normal use of language. It seems most likely that, should there be any difference between the role of the right hemisphere in bilinguals and in unilinguals, it would be in the use of processing strategies relying on right hemisphere capacities, and not in language representation (Gordon & Weide, 1983). This difference could be due to the habitual cognitive style of certain individuals who, in their use of a second language, rely less on syntactic, morphological, and phonological (algorythmic) processes than unilinguals (or than in the use of their own dominant language), and rely more on paralinguistic and situational (heuristic) elements.

This distinction between representation and use of languages may explain some of the contradictions found between clinical and experimental results, the former reflecting deficits in linguistic competence (representation), the latter reflecting defects in the processing of utterances (performance) involving cognitive processes other than grammatical coding, such as access to knowledge of the world, capacity for analogical reasoning, extraction of information from paralinguistic and situational contexts, and from emotional suprasegmental features.

Whatever the participation of the right hemisphere, the more specific question of how the representation of two languages is organized in the...