![]()

1 A Context for CAI

Computers are a powerful instructional medium. Coupled with technological advances such as videodiscs, they can present instruction to meet an ever wider range of educational goals. Tools are available to use this technology with relative ease and efficiency. Remarkable and powerful as they are, these technologies are merely instructional delivery systems, vehicles for presenting instruction. Their impact on education and training depends not on their power alone but on the skill with which they are employed.

The relation between technology and instruction is analogous to the relation between a musical instrument and the sounds we hear. The better the instrument, the greater the potential for beautiful music. But it is the virtuosity with which the instrument is played that determines the quality of the sound. A Stradivarius played by a great artist can stir our very souls, yet that same instrument in the hands of a beginner can make us wince.

Similarly, computers, videodiscs, and the like are merely instruments for producing computer-assisted instruction (CAI) and computer-based training (CBT). The value of the lessons presented depends on the skill of the lesson authors. It is as true today as when the first edition of this volume was published that "Good computer-assisted instruction (CAI) doesn't just happen; authors make it happen" (Steinberg, 1984, p. 1). The purpose of this edition is to help them do so by providing guidelines and principles in the light of recent developments.

Authors today have the benefit of the extensive experience that has been gained designing and implementing CAI. Learning via CAI has increased dramatically in both academic and nonacademic settings such as the military, business, and industry. Between 1985 and 1987, for instance, the percentage of corporations supporting over 100 learning stations for computer-based training rose from 20% to 75% (Hirschbuhl, 1989). The median number of computers in elementary schools more than tripled between 1985 and 1989, with approximately half of that usage for CAI (Becker, 1989). This broad experience makes it possible to identify principles that are generalizable across diverse goals, tasks, and student populations. It also provides insights that cannot be gained from laboratory studies alone.

Research in learning and instruction also contributes to our ability to generate better CAI. Although instruction is still only partly science and partly art, research has demonstrated the importance of a number of elements in learning. These include students' knowledge of the world, their learning processes, and their metacognitive skills, that is, what they know about their learning. Students' strategies for learning also play a significant role.

All together, a synthesis of experience, research in cognition and instruction, and technology opens the way to conceptualizing CAI within a broader context than previously considered and to constructing a framework for understanding CAI. This framework, in turn, provides a structure within which to generate systematic procedures for designing CAI.

The next section proposes a six-component framework for CAI. The rationale for each component is discussed in the light of evidence from research, experience, and/or technology. A procedure for designing CAI follows.

A Framework for CAI

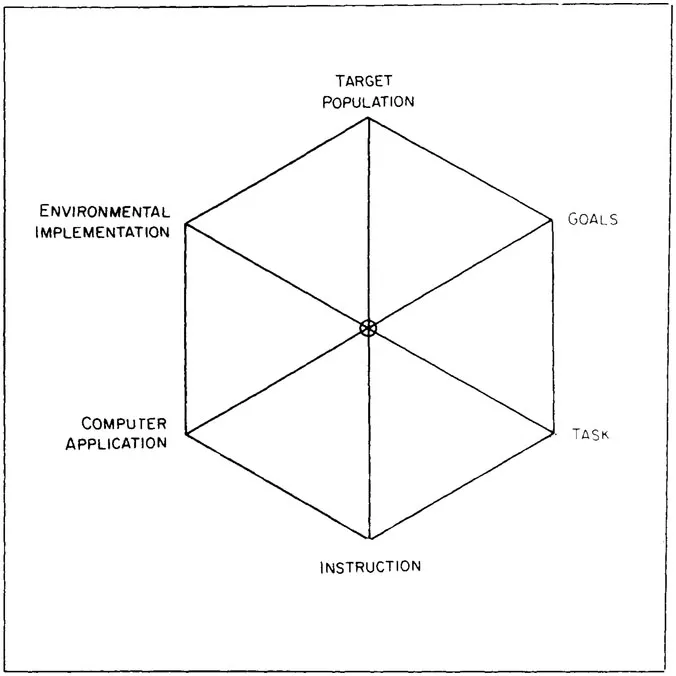

Six components are critical in the design of CAI. They are: Target Population, Goals, Task, Instruction, Computer Application, and Environmental Implementation (see Fig. 1.1). These components do not operate independently. Each interacts with the others and it is this interaction that strongly influences learning and the effectiveness of instruction. The discussion of each component is followed by examples of interactions with other components.

Target Population

Lessons are usually written for a specific group of students, such as first graders. The intended learners are referred to as the target population.

It seems self-evident that lessons should match the characteristics of the target population. Yet the failure of instruction to be appropriate for the

FIG. 1.1.A framework for CAI. (From Steinberg, 1991. Reprinted by permission.)

intended learners is a major cause of unsuccessful lessons in both the corporate world (Hirschbuhl, 1989) and formal school settings (Roblyer, 1988 citing Bialo & Erickson). A cartoon format that is insulting to management trainees might be motivating for less-mature learners. A CAI lesson in structural mechanics designed for engineering students may not be satisfactory for architecture students, because they often lack the mathematical knowledge needed to understand the lesson (Kuznetsov, 1988). A lesson may not even be suitable for all members of a broadly defined target population. For example, in one school system, all first graders were expected to study the IBM Writing To Read reading lessons (IBM, 1987). Although appropriate for many first graders, the activity was not satisfactory for all. One class of bright first graders thought that their computers were broken because the lesson was so repetitive. They learned quickly and expected to advance in the lesson without needless repetition (M. Fortner, personal communication, 1989).

Many characteristics of the target population affect learning, hence the design of instruction. It is obvious that students must have previously acquired the knowledge and skills specifically needed to study a given lesson. This is called prerequisite knowledge. Research in learning as well as experience with CAI demonstrate that prerequisite knowledge is but one of many characteristics that play a significant role in learning. Prior general knowledge, for example, influences a person's ability to comprehend text. The following calculus problem (Sherwood & Taylor, 1946) illustrates the point.

A baseball diamond is a square 90 feet on each side. A player is running to first base at the rate of 30 feet per second. When he has run half way, at what rate is his distance from second base changing? (p. 114)

To solve this problem a person must know where the player starts from as well as the meaning of first base. General knowledge about baseball is just as essential to solving the problem as are the prerequisite mathematics skills.

A student's ability to learn is also influenced by his repertoire of learning strategies. Good learners apply techniques such as stating the main idea, paraphrasing, and reviewing. Good problem solvers know techniques such as drawing a diagram and formulating a plan of action. They also recognize situations where they can apply these strategies.

Developmental level is another characteristic that affects learning. Young children up to the age of about 11 seem to learn better by listening than by reading (Pearson & Fielding, 1982). Some adults also learn better by listening. The implication is that CAI lessons for these learners should not require extensive reading.

Goals

Lessons are written for a purpose, to help learners achieve certain outcomes. These outcomes are called the goals.

Traditional goals. Many of the traditional goals of instruction are also suitable for CAI. CAI lessons can help students acquire a specific body of knowledge, perfect a skill, solve a problem, or modify an attitude. One advantage of CAI over other media is that goals can frequently be achieved in less time in CAI (Kulik, Bangert, & Williams, 1983; Niemic & Walberg, 1987; Orlansky & String, 1981).

New goals. Computer technology makes it possible to set goals that cannot be implemented or that are difficult to achieve via other media. CAI also affords an opportunity to meet management and cost-effectiveness goals.

One goal that CAI is uniquely equipped to handle is to bring students to automaticity, that is, to the point where they can accomplish a task with very little conscious attention. When a task is so complex that the number of subtasks exceeds the information-processing capacity of human beings, some subtasks are brought to automaticity so that most of a person's attention can be devoted to the tasks that require conscious control (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Good readers, for example, decode (sound out) words automatically and devote most of their conscious control to comprehending the message.

To learn a task to the point of automaticity, a student may require hundreds or thousands of trials. CAI can provide this extensive practice and individualize it so that each person practices only as long as necessary to achieve the goal.

Goals that require realistic settings or multimodal presentations (e.g., sound, movement, graphics, text) are now possible, because interactive videodiscs have become economically viable for instruction (Jones & Smith, 1989; Pollak, 1989). Employees can receive training in interpersonal skills before they meet with clients (Sales & Dodd, 1988). Students can observe chemical reactions that are otherwise too hazardous, expensive, or time consuming (Smith & Jones, 1989b). Airplane pilots can learn to manage a tremendous amount of information in a much shorter time than before (Skern, 1989).

In business and industry, computer-based training (CBT) can fulfill both instructional and managerial goals. One goal for employees in many companies, for example, is to learn to use new computer software. Training that involves "hands on" use of the software promotes the transfer of learning from training to job performance. Using a technique known as embedded training, CBT can meet this goal by integrating training with hands on practice. Moreover, CBT provides consistency in training for large numbers of employees and increased control over the training process (Horine & Erickson, 1986).

Interaction of goals with target population. Research demonstrates what seems to be obvious, but is often overlooked. The selection of instructional goals should be appropriate for the developmental and maturational level of the intended learners. Consider, for example, learning strategies and thinking skills, the subject of considerable research (cf. Segal, Chipman, & Glaser, 1985). Some strategies, like summarizing and outlining, help students acquire knowledge. Other strategies, such as setting a goal and monitoring your progress toward that goal, help students manage learning. Young children are capable of learning strategies that help them acquire knowledge such as repetition to remember a short list, but are not likely to acquire management or control strategies (Campione & Arm-bruster, 1985), On the other hand, learning management strategies should be an appropriate goal for college students.

Task

For any given subject, the skills needed to accomplish a task vary with its conceptual difficulty and the cognitive processes required. Applying punctuation rules to a paragraph, for instance, involves different cognitive processes than writing the paragraph. Recognizing an example of a concept entails different skills than generating an example of the concept.

Some skills are essential in many subject matter domains, whereas others are subject-specific. Reading comprehension, for example, is essential to study both chemistry and English literature. However, reading a chemistry book also includes interpreting chemical symbols, but reading a play by Shakespeare does not. On the other hand, reading a Shakespearean play often requires a background in classical mythology that reading chemistry does not.

The nature of the materials may differ from one task to another. Some materials are verbal, others graphic or nonverbal. Using a road map to get somewhere involves different skills than reading directions about how to get there. There is even considerable variance in the skills needed in different kinds of nonverbal materials. It takes different skills to read electric meters than to interpret electric circuits.

Presentation mode also affects the skills needed to accomplish a task. The skills needed to comprehend an oral message in a foreign language differ from those needed to comprehend the same message presented in writing.

Tasks vary in motivational attributes, too. When a task requires extensive practice, students may get bored if they are not intrinsically motivated even though they need to acquire these skills for their jobs. Maintaining high motivation is essential throughout the training period (Schneider, 1985). Schneider provides interesting noises and visual displays, or feedback on their performance to motivate students to work until they attain the specified goal. Kuznetsov (1988) motivates students to practice engineering problems in CAI lessons by presenting a variety of problems and by giving the students the opportunity to improve their scores. If they score poorly on a problem they are allowed to try others and are graded on the problems with the highest scores.

Interaction of task with goals and target population. The nature of a task varies with the goals of the lesson. Consider the Pledge of Allegiance. If the goal is to say the Pledge, the task involves memorization strategies; if the goal is to paraphrase the Pledge, the task requires comprehension. Memorizing the pledge requires only listening and memorizing skills. Paraphrasing, on the other hand, requires reading comprehension and the ability to recast a passage in your own words. Children in the first grade can memorize the Pledge before they learn to read or understand the vocabulary and concepts. Most of them are unlikely to be able to paraphrase it.

For some non-native speakers, comprehending a conversation in English is more difficult over the phone than it is in person. In person they can see the speaker and can compensate for their limited knowledge of English by observing the speaker's body motions and making inferences from them. To understand a telephone conversation they must totally depend on their knowledge of English and on their listening skills.

Instruction

There are significant differences between computer-presented and traditional instruction. These differences affect the instructional techniques, the presentations per se, and the nature of learner-computer interactions.

Differences between CAI and traditional instruction. Learning in the classroom involves interaction among students and among students and instructors. The benefits of interpersonal classroom interactions are not present in CAI. CAI lessons are usually studied individually and may even be studied when no human being is present. Therefore, it is particularly important to make instruction in CAI complete, explicit, and precise.

Instructors in classrooms can estimate whether students are learning by observing their physical actions (e.g., scowling, hand waving) as well as by evaluating students' responses to questions. Computer programs can monitor learning only by evaluating responses to questions. Thus, questions and students' responses to them take on a major role in managing the sequence of instruction in CAI.

The methods of communication are different in CAI than in the classroom. Instructors talk, write, point, and engage in nonverbal actions (e.g., nod to approve). In CAI, instruction is primarily visual at present and students do not have the advantages that might result from the multiple modes of communication in the classroom. Students read, observe, and listen in the classroom; they read, observe, and sometimes listen in CAI. Students respond by speaking, writing, or engaging in body movements in the classroom; in CAI they type, touch, or manipulate a tool such as a mouse. Not all students are adept at using these mechanisms. Students who lack typing skills, for example, find it cumbersome to type a lengthy response. Questions in CAI need to be posed in such a way that students can respond without being burdened by manipulation problems.

Environmental differences between CAI and traditional instruction also influence instruction. In traditional classrooms, students are familiar with the mechanics of studying, such as how to review or how to correct errors. Because students are not likely to be familiar with this kind of information, CAI lessons need to provide it.

Students depend on knowledge about their progress through a lesson to make study plans. They may flip through a manual to see how much they have left to read, or look over a set of exercises to see how many there are. It is not generally easy to look ahead this way in CAI, so authors need to display these kinds of information.

Classroom instructors make numerous management decisions, many of them ad hoc. At the time they are interacting with their students they can decide how much feedback to give when students answer questions incorrectly. Instructors prepare numerous examples before teaching a concept, but they decide how many, and sometimes which examples to present during class time, according to their estimate of how well the class understands the concept. Teachers' decisions about how much instruction to provide, how to sequence instruction, and when to advance from one topic to another are group-based. During group instruction, all students receive...