![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction to Developmental Cognitive Neuropsychology

THEORETICAL QUESTIONS

The questions, which are addressed by developmental cognitive neuropsychology, include:

• How independent are different components of cognitive skills during development?

• Is the modularity seen in studies of adult neuropsychological disorders, mirrored by modularity in development?

• Are developmental neuropsychological disorders explicable against cognitive models?

• What restrictions are there to developmental plasticity? How many routes are there to competence?

• Is there a single developmental pathway?

• What do disorders of cognitive development tell us about normal developmental processes?

As will be reflected in the forthcoming chapters, in certain cognitive domains the field is well developed in conducting relevant studies and analyses to address the questions. In other areas, pertinent studies are just beginning, although interesting routes for future enquiry are evident.

Developmental cognitive neuropsychology has its most recent origins in adult neuropsychology, and an understanding of its history, assumptions and objectives is an important background to any discussion of the developmental field.

ADULT NEUROPSYCHOLOGY

There are currently two distinct approaches to adult neuropsychology; one is broadly more dominant in North America and the other is broadly more dominant in Europe. The approaches differ fundamentally in both their methods and objectives.

The first approach could be called classical neuropsychology and is concerned with the issue of localisation of brain function and the identification of symptoms, characteristic of particular brain disorders. The emphasis has been not upon how the brain conducts a cognitive process but upon where within the brain the process is conducted. This interest in which bits of the brain do what has been a consistent focus of study, since Broca’s (1861) report that productive speech was associated with the third frontal convolution of the left hemisphere. Although some have questioned the utility and validity of the localisation exercise, it has remained a dominant theme throughout the 20th century. Further impetus was provided following the Second World War, when patients became available for study who had circumscribed brain lesions and who displayed a range of cognitive and intellectual deficits (Newcombe, 1969). This enabled the establishment of research programmes, investigating groups of patients typically selected on the basis of a common location of lesion. Standardised or novel tests were then administered to determine what was distinctive about the pattern of cognitive impairment. There was further impetus for such studies, in the days before the widespread availability of brain scanners in a clinical context, since having established knowledge of the patterns of distinctive cognitive impairments linked to specific lesions, in subsequent patients behavioural symptomatology could be used to predict the localisation of a patient’s brain lesion. A similar approach has been adopted with children with acquired brain lesions and in the study of some developmental disorders.

The second approach within adult neuropsychology is more recent in its development. Cognitive neuropsychology is a quite different tradition, established largely in the UK but now the dominant approach to neuropsychology in Europe and certain centres in the US and Canada. The origins of cognitive neuropsychology are found in part within human experimental psychology, as cognitive psychologists and neuropsychologists working together realised that patients with brain lesions could provide data of considerable interest for both testing and developing theories and models of normal cognition. Further, having integrated patient data with theoretical models in cognition, it then became possible to provide theoretically coherent analyses of new patients in relation to the models, which provided a constructive backdrop for both planning remediation and monitoring recovery.

Thus, cognitive neuropsychology has two fundamental aims (Ellis & Young, 1988a). The first aim is “to explain the patterns of impaired and intact cognitive performance seen in brain-damaged patients in terms of damage to one or more components of a theory of normal cognitive functioning”. The second aim is “to draw conclusions about normal, intact cognitive processes from the patterns of impaired and intact capabilities seen in brain-injured patients” (Ellis & Young, 1988a). Group data are far less relevant to this exercise than single cases that showed patterns of dissociation in cognitive function.

Cognitive neuropsychologists have little interest in mapping brain behaviour relationships or describing typical sequelae of brain injury, since this information says little about how the patients are processing information, in functional terms. They are interested in finding, studying and reporting cases which provide information about the architecture of the cognitive processes. They also argue that, without a clear model of how a system is working, it is not always evident which functions one should even be attempting to map. One function of a cognitive model is to represent an analysis of an area of intellectual processing, in which a “black box” is specified in more detail, both in relation to its constituent subcomponents and to the activities of which they are capable (Temple, 1990b). Within those cognitive domains which are now well modelled by cognitive neuropsychology, it has become of interest to determine whether metabolic regional scanners support anatomically discrete localisation of the component elements within the models, by using tasks designed to tap specific elements during activation, but this is a late development in the research objectives. Without a well-formulated view of how a system may operate, the most sophisticated scanners can provide only unfocused information, as the selection of tasks during the activational recording is likely to be inappropriate, generating less informative results.

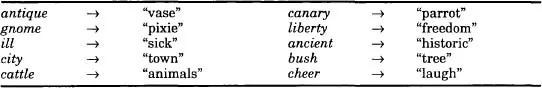

The seminal study in the development of cognitive neuropsychology from which many others were spawned was reported in 1966, with the publication by Marshall and Newcombe of details of a brain-damaged war veteran, GR, who displayed a pattern of reading deficit, which they labelled deep dyslexia. GR had no phonological reading skills, being unable to read aloud even the simplest non-word. Yet, GR could read aloud correctly and understand many concrete words. Errors to single words presented in isolation with no context, were dominated by semantic paralexias (e.g. canary → parrot), for which it was evident that some element of the semantic features of the target had been accessed. The paper was of considerable significance for three reasons. First, it challenged the prevalent models of reading of the time by demonstrating that semantic information could be attained from written text, without the need for a phonologically based access code. It thus contributed, with evidence emerging from studies of normal subjects, to the modification of the previously held model of normal reading, within which phonological decoding of written words preceded any access to a word’s meaning. In similar fashion, the case of KF (Shallice & Warrington, 1970) who had a severe impairment of short-term memory but normal long-term memory, challenged the prevalent view at that time, that short-term memory was a temporary store within which material had to be held en route and before any entry to long-term memory. The modification and enhancement of cognitive models of normal function remains a central objection of cognitive neuropsychology.

The second reason for the significance of the study of GR was that it documented the semantic errors of deep dyslexia which occurred when patients attempted to read aloud individual words presented in isolation (Table 1.1). These errors were intriguing and intrinsically entertaining, and thereby captured the interest of many subsequent researchers. Although such errors could be collated across subjects, analysis of the errors within the distribution of error types from an individual subject, and in relation to other components of reading performance from that subject, was necessary in order to indicate their prevalence and significance. The analysis therefore favoured case studies, another core aspect of many cognitive neuropsychological analyses. If Marshall and Newcombe (1966, 1973), had merely studied GR as one of a group of patients with reading disorders, and averaged performance measures across subjects, the interesting dissociations within the performance of their patient would have been missed. Cognitive neuropsychology emphasises the study of dissociations within subjects, employing them to “carve cognition at its seams” (McCarthy & Warrington, 1990). The performance patterns from individual case studies, are used throughout this book to illustrate particular patterns of performance and highlight the nature of case study analysis.

TABLE 1.1

Examples of Semantic Errors Made in Deep Dyslexia

Source: Marshall and Newcombe, (1966).

The third reason that the Marshall and Newcombe (1966) paper was significant was that it started a trend, albeit one that was initially very slow to gather speed. Further case analyses of the reading and spelling systems using a similar methodology became prevalent through the 1970s and 1980s. Analyses also spread to other cognitive domains: naming, auditory word recognition, syntax, calculation, object and face recognition, motor action, and memory (McCarthy & Warrington, 1990; Parkin, 1996).

This book discusses the application of cognitive neuropsychology to children. This is an approach which is increasingly popular in Europe, particularly in the UK and Italy, but which differs from the dominant approach to child neuropsychology in North America. Whereas adult cognitive neuropsychology builds models on the basis of the disorders seen following functional lesions to a pre-existing system, developmental cognitive neuropsychology builds models on the basis of disorders reflecting functional lesions within developing systems. Like adult cognitive neuropsychology it has two broad aims. The first is to expand models of normal function, using data from children with neuropsychological disorders. Such data is also used to test and contrast different types of developmental model. As with adult cognitive neuropsychology, the aim is to construct a single model of a cognitive domain, or part thereof, against which all childhood cases of disorders of that domain can be explained. In principle, such models, when divided at the seams appropriately, should function in such a way as to generate patterns of cognitive impairment observed in developmental disorders. The second aim has clinical relevance, since there is also interest in the identification of intact subsystems within the developing cognitive framework, which could be utilised in an educational or remedial context.

The most helpful cases in this endeavour are children for whom there are selective deficits, whose dissociation of skills may highlight elements of underlying structure. At its simplest, where one skill has failed to develop and another has developed normally, the development of the normal skill can not be seen to be dependent upon the failed skill. Such information both constrains the possible underlying models and may enable the identification of routes around a selective deficit. In areas where there is limited theoretical background and structure from studies of children, the more detailed models of adult cognition and adult cognitive neuropsychology may provide a useful starting point and background framework to develop new areas of developmental cognitive neuropsychology. There is interest in the success of the initial models as explanatory backdrops for the developmental disorders, since similarities between the developmental and acquired disorders place constraints on the extent to which the developing brain may be capable of reorganisation.

MODULARITY

Current attempts within cognitive neuropsychology to subdivide cognitive processes are based upon a belief in what Fodor (1983) had termed modularity. The idea of modularity derives, in part, from the arguments of Marr (1976) that it would make evolutionary sense if cognitive processes were composed of subparts, with mutual independence, in order that a small change or improvement could be made in one part of the system without the need for there to be consequences extensively throughout the rest of the system. In Fodor’s (1983) writing, the term modularity is used in a very specific sense. The concept has subsequently broadened significantly and as employed in current developmental cognitive neuropsychology it bears only a limited resemblance to the original Fodorian proposals.

Following Marr, it had been argued that it would make evolutionary sense if cognitive processing depended upon separable modules, with each module carrying out its processing, without communicating or overlapping with other modules. Fodor (1983) has termed this property informational encapsulation. However, a slightly more flexible interpretation permits the possibility of some degree of communications between the modules. In such discussions modules are referred to as semi-independent (e.g. Temple, 1991, 1997). Certainly the strict view of information encapsulation as proposed by Fodor has to be abandoned in order to account for studies within experimental psychology indicating cross-module priming effects (e.g. Rhodes & Tremewan, 1993).

Fodor (1983) also argued that modules are domain specific and can only accept one type of input. Modularity, in Fodor’s terms, was therefore not applicable to higher order processes, which may not be subject to such constraints. Others consider that Fodor (1983) was unduly restrictive in the application of the modularity concepts and that these can be applied with just as much success to higher order processes, arguing that executive systems may fractionate (e.g. Ellis & Young, 1988a; Shallice, 1988; Temple, Carney, & Mullarkey, 1996).

Fodor’s (1983) modules are also mandatory and function outside voluntary control. He considered this to be a defining feature of modules. If the operation of a process was not mandatory then it was not modular. However, the ideas of modularity have more recently been applied to systems over which there is voluntary control. For example, the system of retrieving people’s names has many of the required properties of modules, yet is under some degree of voluntary control (e.g. Ellis & Young, 1988a).

The divisions between modules which may arise as a consequence of brain injury reflect fractionation of systems, where selective modules may be impaired while others are left intact. These fractionations are used in the model building of cognitive neuropsychology. Developmental cognitive neuropsychology, uses the same principles when applied to disorders in children. It seeks to explore the concept of modularity within development (Temple, 1991, p. 174):

The advantage of their (modules) semi-independent state in adulthood would be reduced in evolutionary terms, if it had to be acquired through a preceding phase of mutual interdependence and reliance.

There would be an evolutionary advantage if modularity was a principle of the development of systems, since abnormality or malfunction in one aspect of the developing system would not necessarily lead to a reduction in the quality of performance of all other aspects of the system.

A further property that Fodor (1983) proposed for modules was that they are of necessity innate. This view has important implications for developmental cognitive neuropsychology. For if modules are innate, there should be direct parallels between the modular fractionations which can be seen in adult and child disorders and similar underlying models may be used to explicate both areas. This issue is discussed further below in the section on plasticity.

Belief in modularity in development does not necessarily require the nativism of Fodor’s view of modularity. Modules could become established and emerge overtime, with learning as well as, or instead of, innate specifications involved in their delineation. Karmiloff-Smith (1992, p. 5) distinguishes between Fodor’s notion of pre-specified modules and a process of modularisation. In her view:

nature specifies initial biases or predispositions that channel attention to relevant environmental inputs, which in turn affect subsequent brain development … development involves a process of gradual modularisation.

With this view of development, the issues within developmental cognitive neuropsychology concern the ways in which disordered development impinge upon the process of gradual modularisation. Do disorders have a module-specific effect or is Karmiloff-Smith’s system of modularisation so flexible that the end system, in a child with a disorder, will be of fundamentally distinct structure from normal? As Karmiloff-Smith herself points out, her theory relates to the timing of the appearance of modularisation and the degree of pre-specification evident in the neonate. She suggests that biological activation scans may ultimately be able to indicate the degree to which focal specialisation is present at birth. The debate between a pre-specified innate view of modules and a part learning, gradual process of modularisation is relevant whatever the interpretation of the concept of modularity itself. Thus it applies in equal measure to the strict modules of Fodor and to the looser conceptions of modularity which are more pervasive today, within which there may be some degree of communication between modules, more than one type of input may be incorporated (as in the executive disorders) and where processing may have some element of conscious control.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Developmental cognitive neuropsychology is also interested in exploring individual differences between subjects. It is interested in whether there is a single developmental pathway, to the acquisition of a system, or whether there may be parallel routes to accomplishing certain tasks, which may develop across individuals at different rates and with differential strength, thereby generating both considerable individual variation in acquisition patterns and also potentially individual differences in adult cognitive states. The idea of individual variation in acquisition patterns, arising from variation in the development of the parallel routes, differs significantly from traditional developmental descriptions, within which development is often described as developing in a series of stages which are in a fixed order and invariant in sequence. In relation to such stage models individual variation and impairment can only be accounted for in terms of delay in the acquisition of stages. Within developmental cognitive neuropsychology there is the potential for a considerably richer tapestry of accounts of individual variation. The interest in variations in the final adult state achieved differs from much of adult cognitive psychology, which aims primarily to identify areas of invariance across subjects, and works with the premise that single models are applicable to all adult subjects without fundamental differences between people in the architecture of underlying systems. Individual differences are merely perhaps in the databases upon which the systems operate and the nature of the stores which individuals may have established, and which are available during the implementation of a computation. Other individual differences could arise if there are differences in the degree to which components of the functional architecture become established.

These discussions of individual variation assume that there is nevertheless a common end-goal cognitive architecture for the child becoming an adult. A more fundamental account of individual differences would be that the wiring diagrams of the functional architectures achieved may also vary across subjects. If some brains had a fundamental organisational structure which differed from others, then the enterprise of cognitive...