![]()

CHAPTER 1

Drylands, people and land use

CHARACTERISTICS OF DRYLANDS

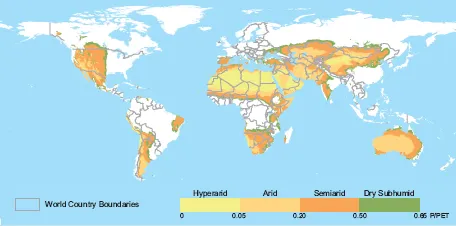

There is no single agreed definition of the term drylands. Two of the most widely accepted definitions are those of FAO and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 2000). FAO has defined drylands as those areas with a length of growing period (LGP) of 1–179 days (FAO, 2000a); this includes regions classified climatically as arid (Plate 1), semi-arid and dry subhumid. The UNCCD classification employs a ratio of annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration (P/PET). This value indicates the maximum quantity of water capable of being lost, as water vapour, in a given climate, by a continuous stretch of vegetation covering the whole ground and well supplied with water. Thus, it includes evaporation from the soil and transpiration from the vegetation from a specific region in a given time interval (WMO, 1990). Under the UNCCD classification, drylands are characterized by a P/PET of between 0.05 and 0.65.

PLATE 1

A view of dryland (with village in the background) in the Sahel, southern Niger (P. Cenini)

According to both classifications, the hyperarid zones (LGP = 0 and P/PET < 0.05), or true deserts, are not included in the drylands and do not have potential for agricultural production, except where irrigation water is available.

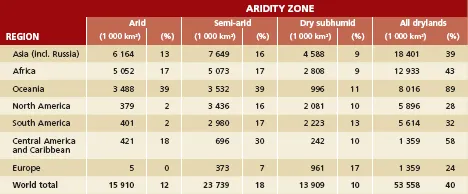

While about 40 percent of the world’s total land area is considered to be drylands (according to the UNCCD classification system), the extent of drylands in various regions ranges from about 20 percent to 90 (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Drylands are a vital part of the earth’s human and physical environments. They encompass grasslands, agricultural lands, forests and urban areas. Dryland ecosystems play a major role in global biophysical processes by reflecting and absorbing solar radiation and maintaining the balance of atmospheric constituents (Ffolliott et al., 2002). They provide much of the world’s grain and livestock, forming the habitat that supports many vegetable species, fruit trees and micro-organisms.

High variability in both rainfall amounts and intensities are characteristics of dryland regions, as are the occurrence of prolonged periods of drought. A drought is defined as a departure from the average or normal conditions, sufficiently prolonged (1-2 years - FAO, 2004) as to affect the hydrological balance and adversely affect ecosystem functioning and the resident populations. There are actually four different ways that drought can be defined (National Weather Service, 2004). Meteorological drought is a measure of the departure of precipitation from normal. Due to climatic differences, a drought in one location may not be a drought in another location. Agricultural drought refers to situations where the amount of soil water is no longer sufficient to meet the needs of a particular crop. Hydrological drought occurs when surface and subsurface water supplies are below normal. Socioeconomic drought describes the situation that occurs when physical water shortages begin to affect people. This report is primarily concerned with agricultural droughts.

The terms drought and aridity are sometimes used interchangeably, but they are different. Aridity refers to the average conditions of limited rainfall and water supplies, not to the departures from the norm, which define a drought. All the characteristics of dryland regions must be recognized in the planning and management of natural and agricultural resources (Jackson, 1989). Because the soils of dryland environments often cannot absorb all of the rain that falls in large storms, water is often lost as runoff (Brooks et al., 1997). At other times, water from a rainfall of low intensity can be lost through evaporation when the rain falls on a dry soil surface. Molden and Oweis (2007) state that as much as 90 percent of the rainfall in arid environments evaporates back into the atmosphere leaving only 10 percent for productive transpiration. Ponce (1995) estimates that only 15 to 25 percent of the precipitation in semiarid regions is used for evapotranspiration and that a similar amount is lost as runoff. Evapotranspiration is the sum of transpiration and evaporation during the period a crop is grown. The remaining 50 to 70 percent is lost as evaporation during periods when beneficial crops are not growing.

TABLE 1

Regional extent of drylands

Source: UNSO/UNDP, 1997.

Three major types of climate are found in drylands: Mediterranean, tropical and continental (although some places present departures from these). Dryland environments are frequently characterized by a relatively cool and dry season, followed by a relatively hot and dry season, and finally, by a moderate and rainy season. There are often significant diurnal fluctuations in temperatures which restricts the growth of plants within these seasons.

The geomorphology of drylands is highly variable. Mountain massifs, plains, pediments, deeply incised ravines and drainage patterns display sharp changes in slope and topography, and a high degree of angularity. Streams and rivers traverse wide floodplains at lower elevations and, at times, are subject to changes of course, often displaying braided patterns. Many of these landforms are covered by unstable sand dunes and sand sheets. Dryland environments are typically windy, mainly because of the scarcity of vegetation or other obstacles that can reduce air movement. Dust storms are also frequent when little or no rain falls.

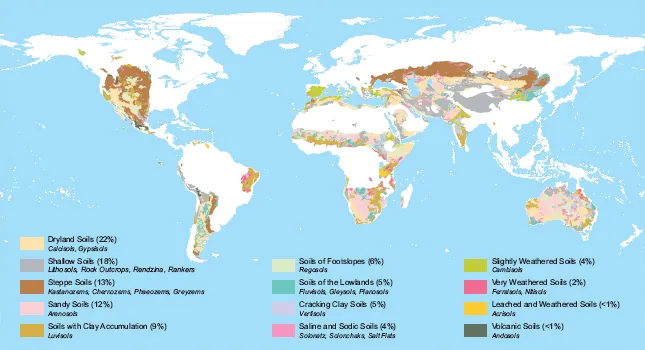

Soils in drylands are diverse in their origin, structure and physicochemical properties. In general, they include Calcisols, Gypsisols. Leptosols and Steppe soils (FAO, 2004) (Figure 2). Important features of dryland soils for agricultural production are their water holding capacity and their ability to supply nutrients to plants. As there is little deposition, accumulation or decomposition of organic material in dryland environments, the organic content of the soils is low and, therefore, natural soil fertility is also low.

Much of the water that is available to people living in drylands regions is found in large rivers that originate in areas of higher elevation (e.g. the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, Indus, Ganges, Senegal, Niger and Colorado Rivers). Groundwater resources can also be available to help support development. However, the relatively limited recharge of groundwater resources is dependent largely on the amount, intensity and duration of the rainfall and soil properties, the latter including the infiltration capacity and waterholding characteristics of the soil, which also influence the amount of surface runoff. With current management practices, much of the rainfall is lost by evapotranspiration or runoff. As a result, groundwater is recharged only locally by seepage through the soil profile. Surface runoff events, soil-moisture storage, and groundwater recharge in dryland regions are generally more variable and less reliable than in more humid regions. In some areas, important reservoirs of fossil ground water exist and continue to be used by human population. Fossil water is groundwater that has remained in an aquifer for millennia. Extraction of fossil groundwater is often called mining because it is a non-renewable resource. For such aquifers, including the vast U.S. Ogallala aquifer, the deep aquifer under the North China Plain, and the Saudi aquifer, depletion can bring pumping to an end. In some cases, farmers can convert to dryland farming, but in arid regions it is the end of farming. Brown (2008) cited a 2001 China study that showed the water table under the North China Plain is falling fast and this area produces over half of the country’s wheat and a third of its maize. He also cited a World Bank study that reported 15 percent of India’s food supply is produced by mining groundwater. Even in areas where groundwater is recharged, it is frequently used at rates that exceed the recharge rate. Water that is available for use in many drylands regions can be affected also by salinity and mineralization (Armitage, 1987).

DRYLANDS PEOPLE

Drylands are inhabited by more than 2 000 million people, nearly 40 percent of the world’s population (White and Nackoney, 2003). Dryland populations are frequently some of the poorest in the world, many subsisting on less than US$1 per day (White et al., 2002).

The population distribution patterns vary within each region and among the climate zones comprising drylands. Regionally, Asia has the largest percentage of population living in drylands: more than 1 400 million people, or 42 percent of the region’s population. Africa has nearly the same percentage of people living in drylands (41 percent) although the total number is smaller at almost 270 million. South America has 30 percent of its population in drylands, or about 87 million people (Table 2).

Rural people living in drylands can be grouped into nomadic, semi-nomadic, transhumant and sedentary smallholder agricultural populations. Nomadic people are found in pastoral groups that depend on livestock for subsistence and, whenever possible, farming as a supplement. Following the irregular distribution of rainfall, they migrate in search of pasture and water for their animals. Semi-nomadic people are also found in pastoral groups that depend largely on livestock and practice agricultural cultivation at a base camp, where they return for varying periods. Transhumant populations combine farming and livestock production during favourable seasons, but seasonally they might migrate along regular routes using vegetation growth patterns of altitudinal changes when forage for grazing diminishes in the farming area. Sedentary (smallholder) farmers practise rainfed or irrigated agriculture (Ffolliott et al., 2002) often combined with livestock production.

The human populations of the drylands live in increasing insecurity due to land degradation and desertification and as the productive land per capita diminishes due to population pressure (Plate 2). The sustainable management of drylands is essential to achieving food security and the conservation of biomass and biodiversity of global significance (UNEP, 2000).

LAND USE SYSTEMS IN DRYLANDS

Dryland farming is generally defined as farming in regions where lack of soil moisture limits crop or pasture production to part of the year. Dryland farming systems are very diverse, including a variety of shifting agriculture systems, annual croplands, home gardens and mixed agriculture–livestock systems, also nomadic pastoral and transhumant systems (Figure 3 and Plate 3). They also include fallow systems and other indigenous intensification systems (FAO, 2004) for soil moisture and soil fertility restoration. Haas, Willis and Bond (1974) defined fallow as a farming practice where and when no crop is grown and all plant growth is controlled by tillage or herbicides during a season when a crop might normally be grown

The major farming systems of the drylands vary according to the agro-ecological conditions of these regions. A recent study of the Land Degradation Assessment in Dryland projects (LADA, 2008) identifie...