CHAPTER 1

Background of Modern Socialist Economics

The term ‘Socialism’ became well established in England in the 1830s, although its first use can be traced back to at least 1826. Since that time Socialism has had an extraordinary career, and less than a century later a British social scientist could compile over 260 definitions of Socialism.1 Today, the regimes which pursue Socialist economic policies can be found in monarchist Sweden and in communist China, in developed France and in underdeveloped Tanzania, in Catholic Argentina, Moslem Algeria and in Buddhist Burma.

However, more specifically, the designation ‘Socialist’ is used to describe the fourteen countries controlled by Communist Parties— nine Eastern European: Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic (or East Germany), Hungary, Poland, Rumania, the USSR and Yugoslavia; four Asian: China (or People’s Republic of China), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (or North Korea), Mongolia and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (or North Vietnam); and Cuba.

To avoid confusion, which on this score is pretty common in the West, it must be pointed out that in Marxian terminology two stages of communism are distinguished. The first stage (called by Marx the ‘lower phase’), or ‘Socialism’, is a transitional stage during which some elements of capitalism are retained. All the fourteen countries listed above are in this stage. Contrary to Western usage, these countries describe themselves as ‘Socialist’ (not ‘Communist’). The second stage (Marx’s ‘higher phase’), or ‘Communism’ is to be marked by an age of plenty, distribution according to needs (not work), the absence of money and the market mechanism, the disappearance of the last vestiges of capitalism and the ultimate ‘withering away’ of the State. The USSR, socially the most advanced Socialist country at present, is vaguely scheduled to start entering the second stage about 1980.2

The subject matter of this book is, as the sub-title conveys, the principles governing the working of the economies of the advanced European Socialist countries which have embarked on far-reaching economic reforms in the last decade or so. This group of countries (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the German D.R., Hungary, Poland, Rumania, the USSR and Yugoslavia) represents one-tenth of world population and one-fifth of world area. It also contributes about 10 per cent of world trade, 20 per cent of world national income and 30 per cent of the world’s industrial output (see Fig. 17, p. 207).

A. The Socialist Economic System

All Socialist countries subscribe to Marxism-Leninism, which in addition to economic philosophy also embodies sociological, moral and political precepts. This system of ideas provides basic guidelines for institutional organization, and the driving force directed towards ensuring social justice. The general characteristics distinguishing the Socialist from the capitalist economic system can be reduced to four fundamental elements.

a. Concentration of Power in the Communist Party Representing the Working Classes. The system of government based on the monoparty rule has important economic implications. The Party provides the continuity of economic policy and it makes overall value judgments. As the national scene is so overwhelmingly dominated by the Party, economic and non-economic objectives are intimately integrated in the State’s totality of actions.

b. Social Ownership of the Means of Production. Most natural resources and capital are socialized, including land, manufacturing industries, banking, finance and domestic and foreign trade. Taking the eight European Socialist countries under consideration as a whole, 92 per cent of farming land is in the socialized (State and cooperative) sector and 95 per cent of the national income is contributed by this sector (for further details, see Chs 4 A, p. 64 and 8 A, p. 114–15).

c. Central Economic Planning. The market mechanism is largely replaced by, or at least substantially supplemented with, economic planning which is normally the responsibility of the State Planning Commission in each Socialist country. Economic processes are subordinated to macrosocial objectives laid down by the Party.

d. Socially-equitable Distribution of National Income. Property incomes (rent, interest, profits) are virtually eliminated whilst earned incomes are based on the quantity and quality of work. Private consumption is supplemented with a very well-developed system of collective goods and services provided free by the State.

However, it must be borne in mind that the former sharp distinctions between capitalist and Socialist economies have been obliterated to some extent by the developments described by some Western thinkers as ‘convergence’ of the two systems. This process is marked by increasing equality, departures from free enterprise and increasing State intervention in the capitalist world, and with liberal economic revisionism incorporating several elements of capitalism in the more developed Socialist countries (for details, see Ch. 15 D).

B. Models Of The Socialist Economy

Up to about the mid-1950s, all Socialist countries had highly centralized economies, all fashioned on the Soviet model developed under the autocratic Stalinist regime. It was generally assumed that this was the only model possible or desirable under Socialism, and those who did not agree could not easily articulate their views. However, the Yugoslav reforms (after 1951), the possibility of ‘different paths to Socialism’ officially acknowledged at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (in 1956), and the remarkable revival of economic thought that followed have effectively undermined the former orthodox uniformity. Today, Socialist economists distinguish four basic models, according to the management of the economy and the consequent method of the allocation of resources. The first two provide highly centralized solutions whilst the other two represent decentralized approaches.

1. The Bureaucratic Centralized Model

In this model, economic processes are dominated by the hierarchical system of planning and management, the Central Planning Authority (CPA) constituting the peak of the pyramid. There is no scope for independence of decision-making at the operational level, as all economic calculation is carried out at the time of the construction of the national plan. Producing units are bound by directive targets and a large number of other directive plan indicators. Economic accounting is done exclusively in physical units, and allocative decisions are not based on prices but on material balances.

The advantage of this model is that it ensures the structure of production according to the priorities postulated by the Party and the internal feasibility of the plan. However, the system is wasteful and it lacks flexibility. Resources are not allocated in the most efficient patterns. Errors in planners’ judgment lead to bottlenecks, shortages and even rationing of consumer goods.

2. The Planometric Centralist Model

The method of physical balances is replaced by mathematical solutions carried out at the CPA level. The system presupposes a well-developed network of computers for collecting, processing and cross-checking economic data. By solving billions of simultaneous equations an input-minimizing or output-maximizing plan variant is arrived at. The interrelationships in the optimal plan provide the basis for optimal prices which are also established computationally. All production decisions are based on these prices, but the actual methods of plan fulfilment at the operational level are left to individual producing units.

In theory, this system provides a considerable degree of flexibility and it can ensure the optimum utilization of resources. However, it is still beyond practical possibility, owing to the insufficiently developed network of computers and the shortage of trained personnel. Furthermore, enforcement of the computational prices in individual enterprises would be a formidable task.

3. A Selectively Decentralized Model

Under this system, central planning and the administrative machinery are retained. But some responsibilities are delegated to branch associations or regional bodies and to enterprises, and they are in a position to influence the central plan. The number of directive indicators is reduced and profitability is accepted as the main criterion of enterprise performance. Prices are still centrally planned but they more closely reflect production costs in order to reduce the need for subsidies and to attain the desired levels of profitability for different branches of the economy. There is freedom of consumer’s choice, but retail prices may be manipulated by the authorities to ensure equilibrium in the market for consumer goods.

This system provides some freedom of initiative for enterprises, within circumscribed limits, and a better deal for consumers. But the price-setting process is not devoid of arbitrary elements, and the allocation of resources is not necessarily placed on the most efficient basis from the standpoint of scarcity-preference relations.

4. Supplemented Market Model

Economic processes are conditioned by the market mechanism, thus replacing annual plans and directive targets. As a rule, prices are determined in the market reflecting supply and demand conditions, but they are corrected by authorities in accordance with long-run macrosocial cost-benefit considerations. Prices provide a guiding function to enterprises endeavouring to maximize their profits, and consumers’ preferences almost entirely determine the allocation of resources to different uses. The role of the greatly reduced body of planners is limited to what Ota Sik (a prominent Czechoslovak economist) calls Orientation planning’—i.e. to determining certain basic proportions (such as those between consumption and investment and amongst different branches of production) and where necessary to initiating key developmental projects. But to achieve the desired objectives, planners essentially rely on fiscal and monetary measures operating through the market.

There are many obvious advantages of this model. The rigidities and waste of bureaucracy are largely removed. There is a sound system of pricing which is conducive to an efficient utilization of resources.

Of the nine European Socialist countries, only two can be fairly easily fitted into these models—Albania as a bureaucratic centralized case, and Yugoslavia as a supplemented market economy. The remaining countries mostly conformed to the first model up to the late 1950s. Since that time, although still retaining several elements of the centralized system, they have been increasingly inclined to embrace the selectively decentralized model. Two of them, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, have gone further and have incorporated several features typical of the supplemented market model. No country has yet adopted the planometric model, but more theoretical and empirical work has been done in this direction in the German D.R., Hungary and the ussr than in other Socialist countries.

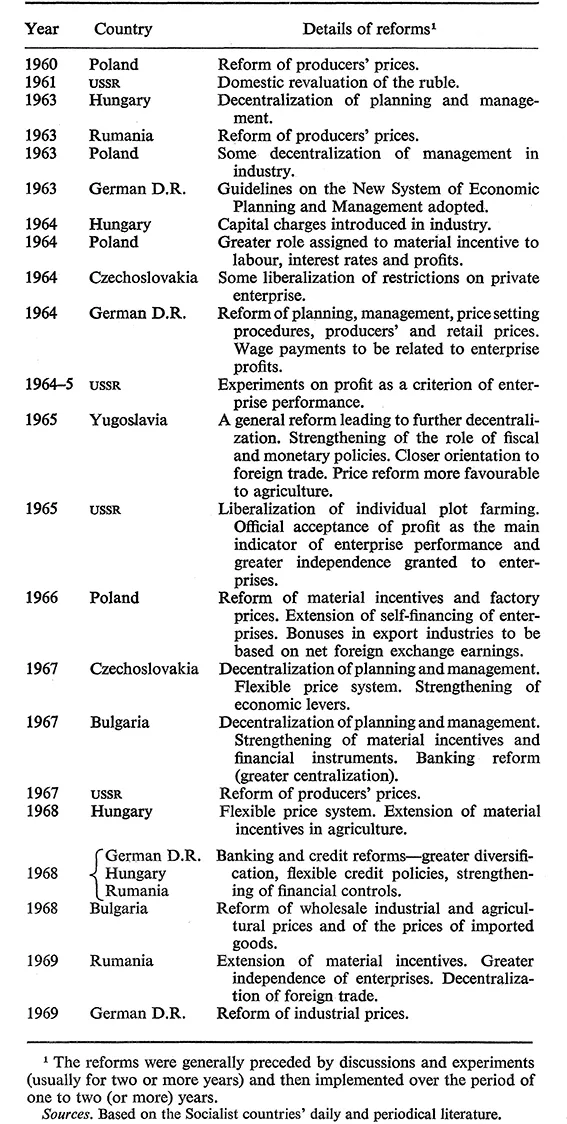

C. Economic Reforms

With the exception of Yugoslavia,3 the economic reforms that were carried out in Eastern Europe and the ussr before 1960 were practically all of the bureaucratic and administrative type. A certain measure of liberalization during 1956–8 in some of them (Poland, the German D.R. and Hungary) was followed by Stalinist-type reactions. A summary of the reforms implemented or initiated since 1960 is presented in Fig. 1. Their general purpose is to increase the efficiency of the Socialist economies which have attained a fairly advanced stage of development. We shall now briefly bring out the significant elements of the reforms common to all the countries under consideration.

FIG. 1. Economic Reforms in the European Socialist Countries since 1960

Liberalization of Planning. Planning is now less prescriptive and detailed. Instead, there is a growing trend to lay down only broad targets expressed in value terms, and there is a shift of emphasis from short-term to long-term (five- to twenty-year) planning. There is closer correspondence between the planning authorities and the enterprises.

A Greater Independence of Enterprises. Industrial and trading enterprises have been given greater freedom to choose the ways and means of plan fulfilment. The hierarchical system of economic relationships is being partly replaced by horizontal dealings between enterprises based on contracts.

Profit. This criterion has been accepted as the main indicator of enterprise performance, whilst the number of directive indicators previously regulating enterprise activities has been greatly reduced.

Strengthening of Material Incentives to Labour. Increased importance is now attached to material, as distinct from moral, incentives. A portion of enterprise profi...